Tyrone Clifford Jr. remembers the first time he tried methamphetamine. “It was everything, all at once,” he said; a whirring rush of euphoric energy. It was the 1990s, and Tyrone was in his early twenties. He was HIV-positive, watching as the AIDS epidemic tore through his community in San Francisco. People he loved were dying. He wanted that feeling of euphoria.

Eventually, having HIV complicated his meth use. Tyrone had stopped taking antiretroviral medicine that suppressed the virus, triggering a series of acute health issues like lymphoma and vasculitis. After these health scares, he had a realization: He wanted help. “You’ve been doing this for 20-plus years, thinking that any minute now you’re going to get sick and die,” he remembered telling himself. “And that doesn’t seem to be how this is going to work. You’re going to be here for a while.”

A psychiatrist at San Francisco General Hospital told Tyrone he needed to go to residential inpatient treatment for his meth use. This wasn’t going to work. His husband had just had surgery and was recovering at home; he’d need Tyrone’s help. The doctor still insisted on inpatient treatment. “I got really irritated with them,” he said. “It’s like, you’re not even listening to me.”

This wasn’t the first time Tyrone felt belittled by the health care system as a gay Black man with HIV. He walked out of that appointment feeling frustrated, with no treatment plan in place. Then he met with his primary care doctor and told her about what had happened. She handed him a slip of paper with the acronym “PROP” written across the top and a phone number on the back.

PROP stands for Positive Reinforcement Opportunity Project, a treatment tailored for LGBTQ+ and nonbinary people who want to reduce their stimulant use. After thinking it over for a couple of weeks, Tyrone showed up for an appointment at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation on Market Street.

Unlike traditional treatments for substance use disorders, which often take place in expensive residential facilities, demand total abstinence from all drugs, and rely heavily on group therapy and the 12 steps, PROP doesn’t punish or control those who participate in the program. Instead, PROP holds substance use on a continuum and gives people the power to determine their own treatment goals: Some might want to be abstinent from all drugs; others might reduce their stimulant use to more manageable levels.

Counseling and group sessions are also part of PROP, but the program is grounded in a highly effective behavioral therapy called contingency management, which reinforces positive behaviors through delivering tangible, often monetary, rewards. “In PROP, I found community, I found support,” Tyrone said. “And it was great to have that money.”

Decades of research show that contingency management works—and is much more effective in treating stimulant use disorders than traditional addiction treatments. But a conservative impulse to punish those who use drugs instead of offering quality care has hardened into policies and laws that prevent contingency management from being more widely used. Instead of infantilizing people who use drugs—how many times have you heard the line about not giving out spare change because they’ll just use it to get high?—PROP treats its participants like adults. People can use the money however they want.

The money can also mean greater freedom. Conventional addiction treatments tend to emphasize models of control—when yours truly was in treatment for an opioid addiction, I wasn’t allowed to drink fully caffeinated coffee or “fraternize” with patients who weren’t my same gender—treating people struggling with their drug use as if they can’t make healthy decisions for themselves. Contingency management rejects this outright.

Recent surges in stimulant-involved overdose deaths—accelerated during the coronavirus pandemic—are creating more interest in contingency management programs, or at the very least exposing the urgency behind the treatment. More people now die from stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine than from prescription opioids like oxycodone, and in 2018 more than a million people in the United States met the criteria for methamphetamine use disorder, which experts consider a massive undercount. Yet very few programs offer effective, science-based treatment. With a growing need for stimulant treatments that work, experts in the field are working to change laws that they see standing in the way of contingency management’s wider adoption.

Tyrone was referred to contingency management because he had little interest in other treatment approaches like the 12 steps, which center concepts like powerlessness and surrender. “I did this, I can undo it,” he told me. “I’m not giving up control.”

Here’s how PROP’s contingency management program works: Participants show up every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday for a drug test. Every time they screen negative for cocaine, amphetamine, or methamphetamine—all stimulants—they are rewarded with money that is deposited into an account managed by the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. Participants can request to cash out at any time. The deeper into the program you get, the more money comes in each deposit. After every three consecutive negative screens, there’s a bonus. The more a behavior is rewarded, the theory goes, the more likely a person is to repeat it.

When Tyrone first entered PROP and heard about the money, he wasn’t ready to commit to never using meth again. He thought, “I can do 12 weeks. And then when I’m done, I’ll have 330 bucks to get high with.” He stayed open-minded enough to engage with the treatment, and his response to it was surprising even to him.

PROP’s 12-week program is capped at $330. As money accrues in their account, participants can withdraw it at any time in the form of a gift card. “That 330 bucks, it can be the difference between someone having food to eat,” Tyrone said. “That could mean the difference between someone having the ability to pay their cell phone bill, which means they can keep their doctors appointments. They can make it to their meetings to keep their benefits.”

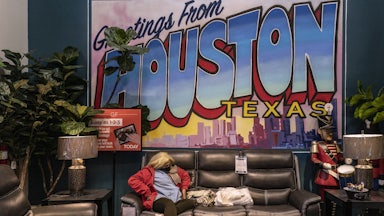

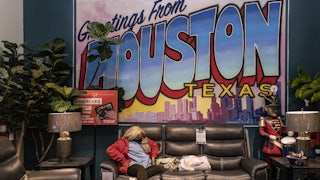

In the beginning, the money from PROP was what helped 50-year-old Billy Lemon stay off methamphetamine. “Day one through Day 30 is rough. It’s just rough,” Lemon said. “But if you can get to four months, the difference between month one and month four is significant. The cash management system from PROP is what got me there.”

With an extra $100 a month while going through treatment, Lemon paid his phone bill, a resource that he said kept him in touch with friends while going through the program. “That’s a big fucking deal,” he said. “It was the impetus that, like, maybe there is a way forward, maybe something is possible.” Being rewarded for not using drugs was a foreign concept. “That somebody is just gonna give me a little bit of money to try and help me make my life better?” Lemon asked. “I can remember having a feeling like: Where’s the catch?”

There wasn’t one. Lemon remembers AIDS Foundation counselors being radically compassionate—they were rooting for him. He didn’t expect it. “Somebody is willing to be on my side and coach me in a good direction, and pay my phone bill while I’m in rehab? With my past, with all the nonsense that I did? That seems like a win, an easy win for folks,” Lemon said. “That we’re not doing this more just seems kind of detached from reality.” Today, eight years after PROP, Lemon is the executive director of Castro Country Club, a queer space that offers support and community for people in recovery.

That sense of understanding, even as it surprised Lemon, is core to the model. In contingency management, no one gets kicked out for using drugs, whether it’s stimulants, alcohol, or cannabis. “I love the harm reduction model,” Lemon, who also attends 12-step meetings, said. “I think it’s much friendlier and kinder, in general.”

In contingency management programs, a positive urine screen does not result in punishment the way it might in other treatment programs, especially when those are court mandated and using drugs can result in jail time. The only negative reinforcement in contingency management is that a positive urine screen means the reward cycle resets, along with the bonus count. You have to start over.

“People can come high,” Mike Discepola, vice president of behavioral and substance use health at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, said. The whole idea of the program is to match a participant’s interest with their ability, Discepola explained. If someone is continually testing positive for stimulants, then treatment, counseling, and care are still available to them. If a participant tests positive, they’re encouraged to discuss why they used, and counselors try to motivate them to keep showing up and try again. No one gets turned away, and no one gets punished for using again.

But that’s exactly what conventional treatment, and the legal system, does. People who use drugs are often given an ultimatum to either comply with an abstinence-focused treatment program or go to jail. In Pennsylvania, one type of probation called “addict supervision” runs on a strict zero-tolerance approach where if participants test positive for drugs, or even miss a drug test, they’re detained and potentially given an even harsher sentence than the one they are hoping to avoid by agreeing to supervision in the first place. All this, mind you, for low-level drug arrests and minor offenses. Federal data from 2012 shows that 44 percent of men aged 19 to 49 who are on probation or parole could benefit from addiction treatment, but just over one-quarter actually get it. Even when they do, it’s hard to know if that treatment is truly grounded in compassionate health care or just punishment by another name.

No one gets rich off contingency management, but the money helps. Rick Andrews, the associate director of the AIDS Foundation’s contingency management program, estimates participants make about $200 on average over the course of 12 weeks at PROP. The research shows the effects of contingency management can last longer than the 12 weeks, but some researchers argue that the option for indefinite use of incentives might be necessary for some. In medicine, when symptoms return after a treatment abruptly ends, that’s a sign that the medicine was working. If someone remained abstinent during contingency management and later returns to using, perhaps that also means the treatment was working. So why cut it short?

Outside the Veterans Health Administration, programs like PROP are hard for stimulant users to come by. Unlike in treating opioid use disorder, there are currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for people who want to reduce their stimulant use, despite promising research showing people addicted to illicit stimulants can be effectively treated when they have a supply of pharmaceutical stimulants. That means behavioral therapies are all that’s available, and research consistently shows contingency management to be one of the most effective.

Dr. Richard Rawson, professor emeritus at UCLA, has studied incentive-based treatment for stimulant disorders for nearly 30 years. Even as an expert in the field, he said he’s unsure of how many true contingency management programs exist but added that “the number is very small.” Federal regulations “have seriously discouraged anyone from doing C.M.,” he said. “I’ve had experiences where people say they are doing C.M., but when I ask specifics I find they are using very low incentives: small gifts, certificates, and candy bars.” That level of incentive is far below the threshold of what’s been found to be effective.

Providing financial incentives is a common practice in health care and most of our regular lives. Employers offer their workers gym memberships and Fitbits to encourage certain behavior. If you’ve ever used points earned on a credit card or accumulated miles from traveling, that’s an incentive, too.

Incentive structures are so ubiquitous because they work. Private insurance companies and even Medicaid offer financial rewards to achieve desirable health outcomes. Incentives can be used to help people quit smoking, adhere to HIV medicine, or engage in preventative care. California’s state Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, implemented a successful incentive of $25 gift cards to low-income women who show up for preventative care like mammogram appointments; the incentive was found to improve appointment attendance.

Researchers and experts in the world of contingency management say that financial incentives aren’t the main problem. Rather, it’s who is being incentivized.

Prevailing stigmas and stereotypes label people who use drugs as selfish, irresponsible, and criminal. Why pay them money? Aren’t they just going to buy more drugs? Attitudes against “coddling” people who use drugs are often deployed to prevent effective harm reduction interventions from being implemented. Rod Rosenstein, Trump’s former deputy attorney general, argued against supervised consumption sites in The New York Times, saying the goal was to “fight drug abuse, not subsidize it.”

Dr. Dominick DePhilippis, a clinical psychologist who helped lead the implementation of contingency management at Veterans Affairs medical centers across the country, has heard it all before. “It may seem a bit hairsplitting, but I don’t even like the terminology of ‘paying people,’” DePhilippis told me. “When I pay someone, I’m compensating them for a service that serves my best interest.” But in contingency management, he said, we are reinforcing a behavior that the patient is choosing for themselves. Patients enrolling in contingency management treatment are told exactly how the program works and what’s expected of them, setting an atmosphere of consent and transparency from the very start.

Since 2011, contingency management has been available to veterans at over 100 Veterans Affairs medical centers. “We are now in our tenth year of implementation, and we have served over 5,400 veterans, and those veterans have provided over 70,000 urine samples, and over 92 percent of those have tested negative for the target substance, typically stimulants,” DePhilippis said. “That’s a statistic we’re very pleased with and very proud of at the VA; it’s comparable to the outcomes seen in the empirical literature.”

DePhilippis credits the success of the VA’s contingency management program to the late Nancy Petry, a behavioral scientist and innovator in the field, who died in 2018 from breast cancer. “You really can’t have a discussion about contingency management without mentioning Nancy Petry,” DePhilippis said. “She was a giant in behavioral science and really revolutionized contingency management.”

Petry is known for inventing the “fishbowl” method, which the VA adopted across its facilities. Instead of receiving a set reward after each negative urine screen, participants draw prize slips at random. Some slips are worth $1, others are worth $20, and there’s one “jumbo” prize worth $100. But other slips have no monetary value and simply say, “Good Job!” After consecutive negative urine screens, the participant gets to draw more slips, increasing their chances of winning more money which is meant to reinforce abstinence over time. Veterans can earn a maximum of roughly $364, and on average earn closer to $200 in prize draws.

“Holiday season is my favorite time of year for C.M.,” DePhilippis said. “Patients who are doing well in C.M. are using their earnings to purchase gifts for loved ones, which is especially poignant because, in many cases, in prior holiday seasons when a patient is struggling, they’re unable to have that joyous experience of buying their loved ones gifts.”

“The need for C.M. is great,” DePhilippis said, referring to rising stimulant-related overdose deaths and a spike in emergency room visits due to methamphetamine. Neither the growing need nor strong evidence has been sufficient to shift attitudes and practices of addiction treatment outside the VA. Because the VA is its own separate health care agency, federal Medicaid rules and regulations like the “anti-kickback statute” do not apply to contingency management programs.

But the “anti-kickback statute,” a criminal law that prohibits “remuneration to induce or reward” patients with money or other gifts, is a huge barrier to implementing effective contingency management at scale. Under current Medicaid rules, remuneration is capped at $75 per patient, per year, and must be doled out in increments no larger than $15 at a time. Contingency management programs set their incentives much higher than that.

The research shows that the value of the incentive matters. Research by Petry shows contingency management programs lose their efficacy when the incentive is set too low. Disrupting a drug addiction requires hard work, and if the monetary reward does not match the effort being put in—abstaining, taking drug tests, showing up for appointments—then people stop responding to the treatment.

Strict rules regarding incentives and inducements stem from a genuine problem of fraud and dangerous practices that have plagued the loosely regulated field of substance use disorder treatment. For instance, the notorious Florida Shuffle is a fraud scheme where unethical “treatment” providers seek patients with robust insurance plans, which “providers” then bill for unnecessary and exorbitant fees while providing shoddy care, if any at all. California is another popular rehab haven, where “no degree, medical or otherwise,” is required to get a license to run a treatment facility. Other predatory treatment facilities force their clients into “work therapy,” which investigations have found can take the form of slave labor.

Programs that engage in fraud and exploitation are nothing like ethical treatment programs that adhere to scientific evidence and are run by clinical professionals: Predatory treatment providers try to control their clients and extract money and labor from them, while contingency management gives people something—money, community, support.

Seeing the efficacy of contingency management, some private insurers and private companies are starting to fill the gap. Newer health-tech companies like DynamiCare, WEconnect, and reSET deliver a combination of therapy and contingency management through phone-based apps. These companies, and the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, can use contingency management because they are not billing Medicaid for the incentive payments. The big hurdle for both these new tech companies and existing programs is to get insurance companies to cover the cost of contingency management as though it’s any other treatment a provider might bill for.

Changing laws and policy is Laura Thomas’s job at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. As the harm reduction policy director, she advocated for lawmakers to craft California Senate Bill 110, which would allow contingency management programs to bill Medi-Cal. “Part of what we’re asking for is the state of California to make it clear to [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] that this needs to change and these types of treatment services are essential in California—not a kickback, not a bribe; they are actually evidence-based treatments,” Thomas said. “Objections to C.M. are essentially stigma turned into bureaucratic regulations.”

There’s no reason that should get in the way of a treatment that works. “I think contingency management is far more respectful of people’s autonomy than some other kinds of treatment that may have a lot more rules, like in residential treatment,” Thomas said. “There’s this popular conception of people who use drugs as zombies, of having no will of their own, of not being able to think, of not being rational.”

Contingency management turns popular myths of addiction on their head, like claims that drugs “hijack” people’s brains, leaving them unable to make decisions for themselves, or ideas about “addictive personality,” as if people who use drugs are intrinsically selfish or egocentric. The contingency management model is based on the science of human behavior, and people who use drugs are human.

That philosophy is what attracted Tyrone to PROP’s contingency management program in the first place. “You were never really penalized. They never took anything away from you. You were never told that you can’t come back,” Tyrone said. “There were times we’d be in the room and there would be guys bouncing off the wall because they were so amped up, and they were treated just as equally and made to feel as welcome as anyone else. For me, that was really important, to feel like, no matter what, I was welcome.”

After completing PROP, Tyrone went back to school to become a counselor. Today, he works for the AIDS Foundation, counseling people who are where he once was. “By the end of that 12 weeks, getting high was the furthest thing from my mind,” he said. That was 10 years ago.