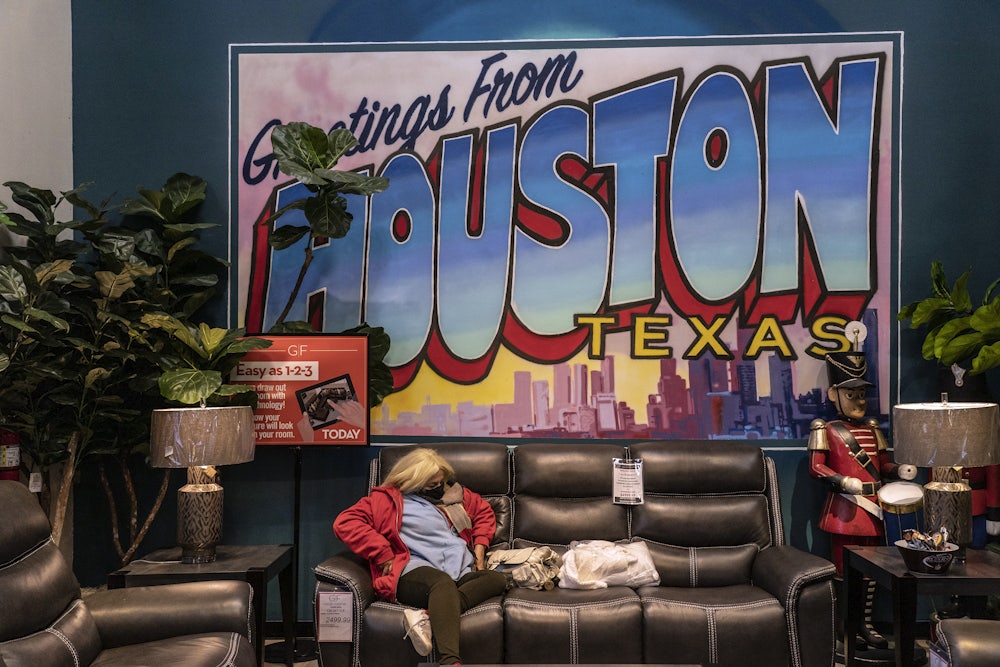

A real estate agent might call our apartment in the Montrose neighborhood of Houston cozy with a sun-drenched bedroom. The reality is that it’s a small, cheap, window-heavy garage conversion. But it’s ours. We’ve filled it with art, good food, books, craft supplies, so many plants, dog toys. It’s our home. Now it makes my skin crawl, a reminder of how fragile these comforts often are.

There are blankets and rugs on the floors to protect feet and paws from the cold wood. There’s a pile of extra coats and sweatshirts in one corner. My girlfriend and I draped a sheet over our headboard so we wouldn’t have to touch the freezing metal and hung a camping lantern from our out-of-commission ceiling fan. Most of the apartment outside the bedroom was made useless, lost to the cold. We each keep a pile on our nightstand—a hat, gloves, and headlamp—in case we need to get up in the middle of the night and venture outside the bubble of precious heat we’ve created. None of this was comfortable, but it wasn’t deadly. At least not for us.

In Harris County, which houses Houston, at least four people are dead from hypothermia as ice and snow covered the streets and temperatures plummeted dangerously low. Counting the surrounding counties, at least 30 people are dead from weather-related incidents, The Washington Post reported on Thursday night. That number is sure to grow as we get a fuller account of the destruction. With each new death, Texans were reminded that asking for the basics was out of bounds. We want our lights to turn on, we want our homes to be habitable, we want our faucets to give us safe water.

The state turned away from us; we turned toward each other. Mutual aid funds populated every major metro area in Texas, giving away money for hotel rooms, food, gas, and the massive energy bills that will follow the disaster—no questions asked. Volunteers with donated water and all-wheel drive helped our elderly, unhoused, and disabled neighbors move to safer places. These groups—Houston’s alone has distributed more than $22,000 to date—became a lifeline.

It’s a beautiful thing born of an ugly thing. We shouldn’t have to donate money to keep us alive because the government is incapable of or indifferent to helping us. But every once in a while, you can see the indifference reveal a deeper contempt. Then–Colorado City Mayor Tim Boyd, in a perfect marriage of content and medium, wrote on Facebook, “No one owes you are [sic] your family anything; nor is it the local government’s responsibility to support you during trying times like this! … The City and County, along with power providers or any other service owes you NOTHING!”

Boyd started his tirade with, “Let me hurt some feelings while I have a minute!!” It’s a succinct enough expression of the modern Texas Republican Party’s beliefs as any I’ve seen. It sees policies as a way of exacting pain on people it despises. When its cruelty is spelled out plainly, you’re the one who is too sensitive. Republicans could never be the ones in the wrong. The ability to stand by that position is Trumpian but predated Trump: Never apologize, and never retreat.

The reality of a changing climate is that we will only become more reliant on each other, and we must decide what kind of world we’d like to live in as it burns—or freezes. In an interview with Texas Monthly, energy consultant and U.T. Austin research assistant in smart grid and bulk electricity systems Joshua Rhodes said that while it’s theoretically possible we might have avoided this week’s energy crisis, there’s also tangible reasons why it happened: Powerful people made choices.

“Could we have built a grid that would have fared better during this time? Of course we could have. But we could also build a car that could survive every crash you could possibly throw at it, but it would be very expensive, and not many people would probably be able to afford it,” he explained. “At some point, we do a cost-benefit analysis of how much risk we are willing to take. We have never had weather like this thrown at us, so it’s not surprising to me that we don’t have infrastructure that can support it.”

Rhodes continued, “We may decide now as a society that we do, but that’s a conversation we’re going to have to have with our collective self, if you will.”

Until such a time comes—and with the knowledge that the state would not provide aid to those who desperately need it—we planned for the storm to the best of our ability. My girlfriend and I were lucky: We had a well-stocked hurricane kit, snow pants from some camping trips we’d taken, more than enough blankets and coats, nonperishable foods, cash, and every lidded pot filled with water while we had water pressure. We only lost power for 36 hours, and it was after Monday—which was when it got down to 14 degrees.

But your own good luck stops mattering after a while, as your anxiety about your loved ones takes over. My grandparents, both in their eighties, lost power on Monday morning and spent the night huddled in layers in one room of their house. They would continue to do so for the next two days. Those days felt frantic. My texts to my abuela would go through green instead of the usual blue because her phone was off. I had no idea when it would turn back on: I just had to pray.

The closest warming shelter to my grandparents didn’t have transport for the elderly, and information felt hard to come by—I still couldn’t figure out if they were open overnight. Joel Osteen had opened his megachurch, but getting them there would require freeway travel, which was itself extremely dangerous.

My parents live just outside of Dallas, near the airport, about five hours north of Houston. North Texas was being hit with much of the same conditions as the south but was closer to the cold eye of the storm. They’re older, both diabetic. My mother is recovering from surgery. They set themselves up in their living room, next to the fireplace. They live at the base of a valley—all hills, nothing flat. Leaving could be deadly. Maybe they could make it to the Hyatt connected to DFW, but again that required freeway travel. I felt paralyzed: Inaction was the safest course of action.

It was hard to know what to do. We only had access to social media flooded with unverified reporting; checking the homepages of The Houston Chronicle, The Dallas Morning News, and the Texas Tribune grounded us. (It also taught me that I need a solar or hand-crank radio.) Instagram became surprisingly helpful; Austin Fox affiliate morning anchor Leslie Rangel had an incredible rundown of the terrible conditions in central Texas. Chronicle reporters filed an impressive liveblog, seemingly answering every question we had about our pipes and when the weather would let up. Despite trying our best to conserve energy on our phones, it was our only lifeline, and our battery banks became precious.

By week’s end, everyone in my family had their power back. Things were thawing. We had been spared. Spared by the fact of enough disposable income to buy those hurricane supplies. By the timing of our power outage. By bodies that were able to carry us down stairs and easily move in the cold. By jobs that shut down for two days and let us focus on surviving.

Not everyone had luck on their side. Texans were already hurting because of the pandemic. At least 41,000 people filed unemployed due to Covid-19 this week. Houston only passed an eviction grace period this week. Plus, to state the obvious, homes in Houston and along the Gulf shores are not meant to protect from this type of winter weather. Even if you were only marginally affected by the pandemic, but lost power in Galveston, you were in real danger.

If I sit with this governmental abandonment too long, it makes me seethe with rage. I feel it radiate at Ted Cruz leaving us for Cancún, and John Cornyn’s culture-war bullshit when power was already out, and Rick Perry saying people would want longer blackouts to stop regulation, or Greg Abbott blaming wind power and the not-enacted Green New Deal for the blackouts. I feel this rage at the long line of Republican governors and legislators who value markets over human life.

People across my state are dead. They deserve the truth to be told about their deaths. Their government did not adequately prepare them for a climate change disaster. Their government did not adequately prepare itself for this climate change disaster. And there will be more storms. We’ve seen disasters that the state has turned away from, never learned anything like a lesson from the loss of life or the scale of suffering. What’s more upsetting is that Texans who have lived through climate disasters support solutions. In 2020, the University of Houston found that three years after Hurricane Harvey, people whose homes were devastated by the 50-plus inches of rain dumped on southeast Texas overwhelmingly support flood-mitigation efforts, but only 52 percent are “somewhat” or “very confident” in local officials to prevent future flooding trauma. Rick Perry doesn’t know anything about his state.

The most frightening part of the experience was coming out from the fog only to realize that the machine to forget was well oiled and running. As the climate crisis worsens, we will continue to see these “500-year” weather events. What happened this week was extraordinary. It was a catastrophe. How we were treated this week was unacceptable. How Texans were treated during Hurricane Harvey was unacceptable—was also a catastrophe. How Puerto Ricans were treated during Maria was unacceptable—another catastrophe. But our political system is built around forgetting, around powerful people who would like us to turn away from the things we’ve lived through—trapped in our homes, shivering—and turn away from each other. I keep hearing that I’m living through extraordinary times, and I guess that’s true. But we know this won’t stay extraordinary for long.