Two months before armed insurrectionists stormed the Capitol, the first major operation to “Stop the Steal” went down in Philadelphia. On November 5, Joshua Macias, a former Navy petty officer, and his partner, Antonio LaMotta, a self-described “private security company CEO” and “artist” who’d served in the Army, drove a silver Hummer adorned with QAnon stickers from their Virginia hometown to the Philadelphia Convention Center, where officials were counting ballots. Packed inside the SUV were handguns, an AR-15–style rifle, 160 rounds of ammunition, and a samurai sword.

Luckily, law enforcement managed to apprehend Macias and LaMotta as they approached the convention center on foot, armed and under the cover of darkness. They were soon released on bail, and a few months later, according to prosecutors, both men traveled to Washington, D.C., to help incite a riot. On the night before violence gripped the Capitol, Macias took to Facebook Live, declaring that “the enemy is here, it’s not just at the gate, it’s within, we see it everywhere.”

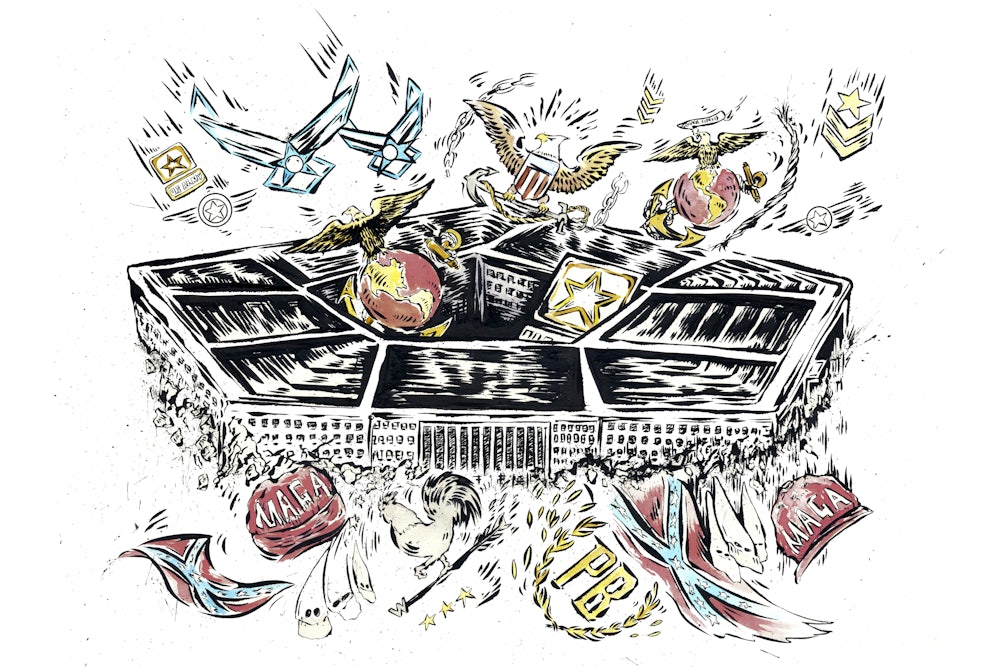

Current and former service members were scattered throughout the sea of rioters on January 6: Adam Newbold, a former Navy SEAL, confessed he was eager to leave lawmakers “shaking in their shoes.” Donovan Crowl, a Marine veteran, said he served as “security” for an unnamed group of “VIPs.” Emily Rainey, an Army psychological operations officer, had ferried roughly 100 followers to Washington from North Carolina. As rioters charged up the steps of the Capitol, men in battle gear formed a tactical line known as a “Ranger File”—a “chilling sign,” according to The Associated Press, that many who “stormed the seat of American democracy either had military training or were trained by those who did.” Larry Rendall Brock Jr., a retired Air Force officer, arrived on the Senate floor armed with zip-tie handcuffs. He and others seemed to be rifling through members’ desks as part of what Brock described as an “information operation.” On the other end of the Capitol, a police officer shot and killed Ashli Babbitt, an Air Force veteran turned Trump devotee and QAnon disciple, as she tried to enter the speaker’s suite. Four others died in what appeared to be the first battle of a cold civil war.

Nearly 20 percent of those who’d been charged by late January for their alleged involvement in the riot had a military background, according to an analysis by NPR. Facing intense scrutiny, the Joint Chiefs of Staff released a memo reminding service members that “any act to disrupt the constitutional process is not only against our traditions, values and oath, it is against the law.” A Pentagon official later vowed, “we will not tolerate extremism.” Yet these were half measures from a deeply complicit party. While Trump incited the January 6 riot, the military created the conditions that led to its staggering power.

It may seem bizarre that guerrillas are now trying to tear down a country they once swore to protect. But America’s military institutions breed such upheaval. The Pentagon’s core work involves a volatile mixture of murder and mythmaking. When service members spot a lie, experience mistreatment, or otherwise become disenchanted with their government, some lose faith in the mission, but not in the mindset the military instilled in them. These people are now teaching hand signals, battle formations, and other boot camp skills to similarly aggrieved Americans as part of a bloody revenge plot.

In her 2018 book, Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America, the historian Kathleen Belew traces how vigilante violence and Ku Klux Klan membership have often spiked when troops return from battle. “All of American society becomes more violent after warfare,” she explained in a 2019 speech.

Vietnam, for instance, thoroughly scrambled the psyche of the American warrior and instilled in troops a deep disdain for, and distrust of, government. It also resulted in fictionalized and racist retellings of war narratives meant to keep up an air of Western superiority. These stories radicalized veterans like Louis Beam, a KKK leader who targeted Vietnamese fishermen in Texas, and Frazier Glenn Miller, founder of the White Patriot Party, who shot up a Jewish community center in Kansas in 2014. They established strong but leaderless hate networks for subsequent generations of veterans, such as Randy Weaver of Ruby Ridge fame and Timothy McVeigh, the architect of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.

The military has long known that homebrewed hate flourished within its ranks, but has done little about it. In 1998, a Defense Department report found that far-right groups were targeting young recruits to gain access to weapons and military training.

Tragically, this warning didn’t resonate. By 2009, the Department of Homeland Security was noting the growing links between veterans and domestic terrorism. Thousands of veterans were returning home from Afghanistan and Iraq disillusioned and angry—at the generals who had sent them to search for weapons that never existed, and at the war itself, for breaking the promise of Western democracy in the Middle East. Some turned to conspiracy theories and found a new righteous fight on the radical right.

It’s never been easier for the far right to find followers. While Beam radicalized the Cold War generation through a crude message board called Liberty Net, veterans of the war on terrorism encounter far more powerful recruitment networks in Stormfront, 4chan, and Facebook. There’s now also profound distrust in American government, easy access to weapons, and Republican leaders stoking violence.

Today, the Pentagon can’t even assess how many of its members are radicalized. Those in power are promising to fight extremism by falling back on tired solutions drawn from our failed Forever Wars: a surge of National Guard members to secure the inauguration, or a new domestic terrorism law. Meghan McCain even floated sending Capitol Hill rioters to Guantánamo Bay.

Violent schemers should be punished, to be sure. But empowering the arm of government that got us here will only make this country sicker. What’s needed now is an exorcism of military arrogance and influence from the American soul—by withdrawing from the Middle East and Afghanistan and extinguishing our thirst for international power. We must disempower our weapons industry, audit the Pentagon, and funnel resources into the Department of Veterans Affairs, which, through its provision of free health care and good benefits, helps neutralize hate. Politicians should punish, not pardon, war criminals, and the media must end its dalliance with missile strikes and Navy SEALs. In other words, we must disarm, culturally, politically, tactically. For once, let’s give peace a chance.