“Unity” is an elusive word in American politics. More often than not, it suggests something utopian and silly—the promise of an end to partisanship, an epiphanic recognition of a common interest after years of squabbling. It asserts the notion that our divisions are artificial constructs, pushed onto us by conflict-oriented media and snake-oil-spewing partisans—whatever it may seem on the surface, deep down we are actually in complete agreement with one another about what to do. And what is that thing we should do? Whatever the elite consensus holds it to be. To do anything else would be “divisive.”

Republicans have, over the past couple of weeks, striven to redefine unity along these lines: whatever Republicans want, to the exclusion of anything else. Impeaching the president for inciting an insurrection against Congress? That doesn’t unite the country! Ending a travel ban from Muslim-majority countries? Sorry, that doesn’t bring us together! Allowing transgender soldiers to serve in the military? Gosh, what divisive idea will Joe Biden think of next?

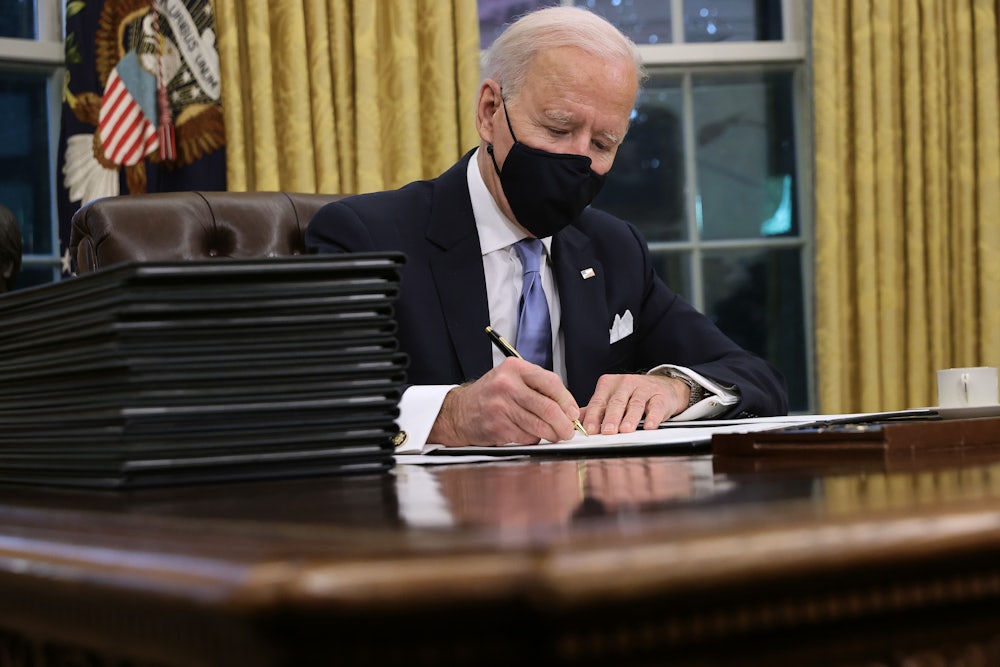

It is, as Greg Sargent noted, a familiar trap. Joe Biden has, both on the campaign trail and in his inaugural address, pledged to unite the country. It’s a pleasing enough sentiment while campaigning, but there’s a risk once the election is won that’s playing out now. Republicans can attempt to claim veto power over the very concept of unity, arguing that Biden violates that creed any time he breaks with the authoritarian policies of his predecessor. As Sargent argued, it’s an effort to “game the media into saying Biden is already reneging on his unity promise by being divisive.” It’s a big scam, in other words, one that allows hard partisans to define terms: If Joe Biden actually cared about the country, he would bring it together by governing exactly like the least popular president in modern American history.

It’s just more obvious bad-faith nonsense. Biden is doing the things he pledged to do on the campaign trail, most of which are broadly popular—allowing transgender soldiers to serve in the military is supported by 71 percent of Americans and 63 percent of Republicans. That’s pretty unifying—to do things that are supported by considerably more Americans (and Republicans) than voted to elect you in the first place.

Republicans playing with the fringe idea that these broadly popular policies aren’t unifying are, to some extent, merely aiming this rhetoric at the GOP’s rabid base. But they’re also working the refs, pushing a political media that’s naturally addicted to partisan conflict to give Biden’s unity pledge the classic “both-sides” treatment: Biden said he would govern as a uniter, and yet he’s going to allow people from Eritrea to visit the country again? What gives?

Naturally, the press are absolute suckers for this con. On Thursday, Biden’s first full day in office, New York Times reporter Michael Shear asked White House press secretary Jen Psaki, “Where is the actual action behind this idea of bipartisanship? And when are we going to see one of those sort of substantial outreaches that says, ‘This is something that the Republicans want to do, too?’” It’s hard to know what Republicans “want to do.” Last time anyone checked, it was “throw out the electoral votes of several states.”

On Sunday’s Meet the Press, Chuck Todd noted that “Joe Biden stressed a theme of unity in his inaugural address,” but “moving on from rhetoric, Mr. Biden went to work immediately to erase much of what he could with a pen of Donald Trump’s presidency”—the very thing Biden promised to do on the campaign trail. A since-deleted tweet from ABC reported that “roughly one-third” of Americans opposed America’s reentry into the Paris Climate Accord, another promise Biden made during the election cycle. As a “data journalist” might note, another way of communicating that story would be simply to say that the vast majority of Americans approve of Biden’s actions. A Saturday headline in The New York Times made unity itself the source of partisan conflict: “In Biden’s Washington, Democrats and Republicans Are Not United on ‘Unity.’” How postmodern!

Biden can definitely be faulted: for promising this rose garden and setting a trap for himself in the first place. Rosy statements on the campaign trail about Republicans coming to their senses after Trump’s defeat were fantasies. “With Trump gone, you’re going to begin to see things change,” he said. “Because these folks know better. They know this isn’t what they’re supposed to be doing.” That was never going to happen—and people around him surely knew it. But these optimistic statements allowed Biden’s unity pledge to take on a skewed dimension, in which a promise to do things that either benefited the majority of Americans or were popular with swathes of the electorate became a promise actually to get Republicans to join a bipartisan campfire circle.

Still, much of Biden’s rhetoric can be reasonably understood as a sensible way of doing politics.

Donald Trump rarely did anything to expand his base of support beyond the voters who put him in office. He spent his term antagonizing the people he could have brought into the fold, while governing poorly enough to alienate a significant portion of those who put him in the White House. Biden’s unity pledge can be best understood as a promise not to govern in a fashion that actively seeks to alienate and humiliate the people who didn’t vote for him—his “unity” is about governing for the common interest, as opposed to governing for a slice of the population, or as was too often the case with Trump, a narrow slice of bootlicking hangers-on and blood relatives.

Biden has argued that unity is about governing from a consensus beyond the Beltway; finding kitchen-table issues that a broad majority of Americans support. “Unity also is trying to reflect what the majority of the American people—Democrat, Republican, independent—think is within the fulcrum of what needs to be done to make their lives and the lives of Americans better,” he said.

The critics of Biden’s “unity” on the right are aided by a press that is unable to think beyond partisanship and partisan conflict. If Republicans say something is divisive—even, and perhaps especially, if it is broadly popular—it is treated as division. The press is hard-wired to cover the shiny sparks of ideologies clashing on Capitol Hill and is not particularly adept at reaching beyond the narrow confines of Washington D.C. (Indeed, when it does venture out into the real world it is, more often than not, to discover what highly partisan Republicans think about politics.)

“When it comes to Biden and unity, we need more sophisticated metrics than cabinet berths and legislative capitulations,” wrote Columbia Journalism Review’s Jon Allsop on Monday. The current makeup of the parties—and the GOP’s refusal to give an inch to the new administration—requires the press to think beyond these categories. The press has some long-overdue soul-searching to do about how it’s made it the status quo in Washington always to punish the party seeking the higher standard while letting the vandals skate. Already, the media is punishing Biden, and rewarding Republicans, for the fractiousness of the GOP.

High-information journalists should find it easy to call bullshit on Republicans. Not only did the GOP spend the last four years doing nothing to “unite” the country in any sense of the word—either governing for consensus or reaching across the aisle—but the party’s leadership stood behind Donald Trump as he attempted to overturn a lawful election. Against that backdrop, it’s more than a little ludicrous to hype Biden as a divider for rejoining the Paris climate accord, allowing transgender soldiers in the military, providing cash payments as economic stimulus—very popular things that Americans want and that Republicans oppose for reasons that don’t get properly interrogated. It’s a scam that reporters don’t have to fall for. The right follow-up question anytime a Republican whines to the press about Biden’s alleged divisiveness is simple: What have you done for unity, lately?