Never in living memory has late December been so welcome; 2020, the year that lasted centuries, is nearly done. A lot of us didn’t make it. But for all the anxiety that mounted throughout the summer and fall as the presidential election drew nigh, Trump’s attempts to bring about the worst-case scenario—a stolen election or descent into civil war—appear to have failed. The creaking, gerrymandered, lobbyist-leased massage table that we call American democracy has survived another season. Fresh calamities notwithstanding, Joe Biden will be sworn in as president on January 20, by which time Donald and Melania will have emptied their night tables and packed their many gilded bags. So why is it still so hard to exhale?

In the giddy hangover of the election’s endless final act, it was possible to feel, if not actual rejoicing, at least some hearty schadenfreude-tinged relief. A knot that had been getting tighter every day for months suddenly unraveled. That sensation didn’t last. The lines on the graphs tracking the spread of Covid-19 soon went nearly vertical. New daily cases topped 100,000 the day after the election and have since more than doubled that again. Just as the contours of the new political reality are beginning to reveal themselves, a familiar sense of grief and dread has returned. We may have escaped the gory dismemberment that four more years of Trump would have unleashed, but we did not dodge a bullet.

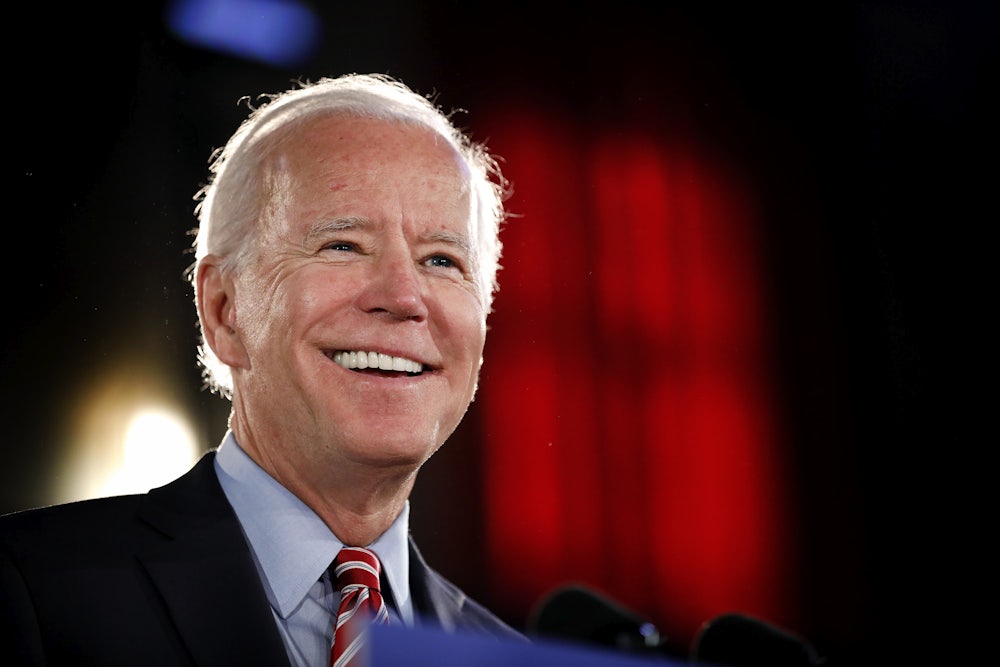

It is nonetheless a genuine comfort that we will soon have a president capable of talking about something other than himself and an ever-expanding throng of imaginary enemies, from rapist immigrants to antifa thugs. What Joe Biden says is almost without exception timid, bland, and entirely inadequate to the urgency of the moment, but he knows enough to acknowledge the real forces that are mowing us down. He talks about the pandemic, the climate crisis, and sometimes, if only glancingly, about racism as a structural problem. With the virus raging, the one major marketing point of the down-home technocratic neoliberalism that Biden represents—institutional competence—can feel inordinately reassuring.

But if Biden’s presidency stands for anything other than a return to a certain baseline rationality, it is for a vision of the past that had already expired when Trump took office four year ago. The most consistent message that Biden has had on offer since the campaign began is a nostalgia for the comparatively soporific years of his vice-presidency. Who hasn’t dreamed of a politics that’s boring? The Trump administration, in this vision, takes shape as an anomalous interregnum. Where Bernie Sanders spoke rashly of revolution, Joe Biden will install a restoration. His transition team and cabinet picks—an ethnically diverse, ideologically uniform cast of centrist thinktankers, Obama appointees, corporate execs and lobbyists—all signal a return to pre-2017 politics as usual.

Trump also campaigned on nostalgia. He sold a vision of white America that was never anything but great, unsullied by slavery, genocide, and all the crimes of empire. In response, Biden conjured a magical suturing of wounds that are themselves better left unmentioned: “Let us be the nation that we know we can,” he intoned in his victory speech, echoing Obama. “A nation united … A nation healed.” It is hard not to notice that the one lyric from the Clinton-Obama hymnal that Biden doesn’t often utter is “change”—and harder still to forget that he assured wealthy donors in June that, were he elected, “nothing would fundamentally change.” The other notes he routinely hits are all familiar: “hope,” “unity,” “faith in America,” “faith in tomorrow”—with “tomorrow” understood as a vague and feel-good placeholder, like in the showtune and not as another hard day that will arrive, irrevocably, at midnight.

The nostalgia Biden evokes is not only for the relative sobriety of the Obama years but for the interrupted narrative of national atonement that the ex-president embodied. Obama could talk about slavery as “original sin,” about segregation and Jim Crow, and then offer himself up as evidence that, however enormous such past injustices may be, we remain “on the path of a more perfect union.” The sustaining fantasy of his administration was that the ghosts that haunt us were losing the battle for the country’s soul, that we were not damned to inequality and violence, that we could “choose our better history,” and that, echoing Lincoln, “our better angels” might prevail. The system could be made to work for everyone.

Long before Trump bulldozed through that dream, the subterfuge was obvious. Obama’s actions carried the same message that Biden clumsily voiced aloud: Nothing would fundamentally change. His eight golden years began with a $29 trillion Wall Street bailout that initiated a massive transfer of wealth that left most Americans, and particularly African Americans, poorer at the end of the Obama-Biden era than they were at the beginning. It is easy now to forget that it was under Obama, in the wake of Trayvon Martin’s murder and then Michael Brown’s, that activists found it necessary to insist that Black lives really do matter. Ferguson in August 2014 didn’t look much different than Minneapolis did this May.

Still, it is that same haggard fantasy that Biden is attempting to resurrect, the consoling illusion that past crimes can be absolved without any major rupture. Biden is neither as smart nor as eloquent as Obama, and he mainly makes a hash of it, reminding us of his ability to collaborate with segregationists instead of plumping our sense of multicultural imperial destiny. With camouflaged militias stalking statehouses and their apologists still occupying the executive and legislative branches, Biden’s calls for unity could not sound more impotent. But even if he were a more capable orator, no amount of rhetoric will jam the demons that Trump unleashed back into the cracks in which Obama had tried to stuff them.

The old neoliberal sleight of hand, substituting diversity for substantive equality, won’t work this time. The rupture has already happened. Trump spent four years shoving his tiny fingers into every fissure he could find in the American body politic. The ghosts, it turned out, were not even sleeping. They came racing out into the light, not only the ghouls but those better angels too—the ones Obama and Biden both trot out as needed for lyrical effect but disown when they make actual demands. They were angry, and they did what the more reputable class of angels have always done in this country. They animated flesh-and-blood Americans to stand up and risk everything—the bullets of their countrymen, the batons and prisons of the authorities, and, this time, the virus too.

Summer feels like a long time ago, but it would be worse than stupid to forget that this year the United States experienced something at least as historic as the pandemic: the largest protest movement in our history. Without lectures from above, people in the streets made the connections between contemporary police killings and the centuries of racial violence that preceded them. However you feel about the historical value of marble monuments to slavers, the toppling of all those statues made it clear that these were not blind outbursts of desperation but the beginning of a reckoning long overdue. With as many as 40 million Americans facing evictions in the coming months, around 80 percent of them Black and brown, it won’t likely be postponed much longer.

Back in the capital, Biden’s chestnuts about unity are unlikely to budge a Republican Senate majority that, though it represents a minority of the population, has shown itself willing to let the country collapse before ceding an inch in the class war. And war it is: The same Republicans who eagerly transferred more than $1 trillion from public coffers to corporations and billionaires refused to give unemployed Americans more than an extra $300 a month or to release emergency funding to state and local governments crippled by the worst economic crisis since the Depression. Still, with food bank lines stretching for miles and more than six million eviction orders expected to go out as soon as the current moratorium expires, Biden has shown no sign of being ready for a fight. If anything, he is more comfortable on the side of the kleptocrats: Biden intervened in the stimulus negotiations, The New York Times reported, to support a package that amounted to less than half the funds that the centrist Democratic leadership had been pushing for, giving “Democrats confidence to pull back on their demands.” His most recent pandemic response plan does not say a word about hunger, housing, unemployment, sick leave, or access to care—as if poverty were not among Covid-19’s most lethal comorbidities.

Political paralysis is undoubtedly preferable to the race straight into the abyss that a second Trump administration would have brought. But the abyss is getting closer whether we move toward it or not. The pain of this coming year will make itself felt in the vast gulf between what needs to be done to stave off catastrophe and what is remotely feasible given the political conjuncture. The virus rages, the planet warms, and here we are: knowing that this broken system cannot save us; knowing that we will be the ones who have to fight; knowing that our losses will be terrible; knowing that we have no other choice.