For one ever-so-fleeting moment after the Capitol Hill riot earlier this month, it looked as if the GOP might take decisive action against Donald Trump. Ten House Republicans voted to impeach him for incitement of insurrection one week after the attack. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell floated the possibility that he would vote to convict him. Even those who were ostensibly defending Trump, like House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, said he bore responsibility for what happened.

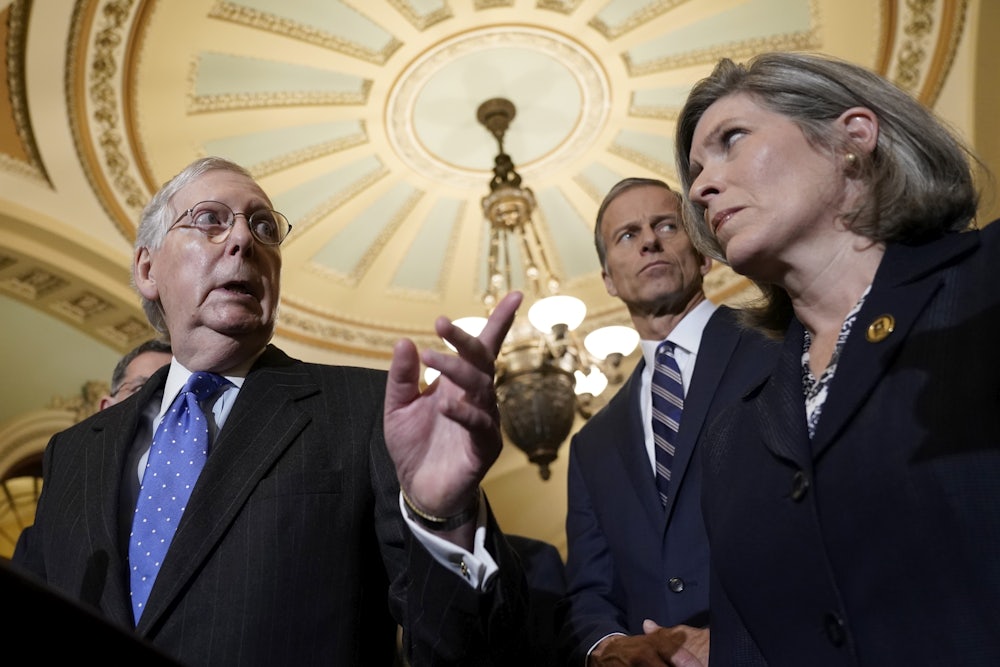

Three weeks after the worst attack on the Capitol since the British burned down Washington, that window for accountability has closed. Two-thirds of senators must find Trump guilty to convict him. It does not look like 17 Republican senators are eager to vote that way. Trump’s departure from the spotlight helped shift attention away from what happened, as did the focus on the incoming administration. “The initial sense of urgency to hold Trump accountable and senators’ clarity about what they experienced that day both diminish as time passes and partisans spin the facts to try to cast Trump and his allies in a better light,” The Dispatch noted on Tuesday.

There’s an irony here, of course. Thirty of the 50 Republican senators currently in office aren’t up for reelection for at least another four years. They are somewhat insulated from the whims of their constituents. That’s by design. The Senate’s peculiar nature is often justified as a check against the passions of the moment—as a bulwark of sorts against rise-and-fall demagogues and inflamed political moments. If the Senate can’t fulfill that duty, then what purpose does it serve?

No part of the American political system is immune to scrutiny or criticism, but the Senate attracts an outsize share for good reason. Equal representation among the states is a structural boon for sparsely populated rural regions, lending disproportionate influence to whichever party is strongest among voters there. The modern filibuster is a perpetual kneecap to the legislative process. It hinders policy proposals and weakens Congress as an institution. The Senate’s byzantine structure and arcane rules seem designed to frustrate basic democratic governance.

Whenever these arguments are raised, the Senate’s defenders reply, “Well, yeah, that’s the point.” They refer to the allegorical tale in which George Washington, when asked by Thomas Jefferson about the Senate’s purpose, compared it to the cooling saucer for a teacup. They claim that the chamber’s design forces legislation to receive support from a broad cross-section of the country, ensuring its long-term survival.

Since the chamber’s seats aren’t apportioned by population, and because it was originally unelected, the Framers also described it as a bulwark against the temporary passions that might arise from the elected branches. The six-year terms for senators would guard against whatever passing fads might inflame the House from time to time. “In order to judge of the form to be given to this institution, it will be proper to take a view of the ends to be served by it,” James Madison explained at the Constitutional Convention. “These were first, to protect the people against their rulers, secondly, to protect the people against the transient impressions into which they themselves might be led.”

Over time, the Senate’s defenders began to inch away from the Framers’ openly anti-democratic rhetoric. They no longer held up the chamber as a defense against “agrarian interests” or said it would prevent a “leveling” effect against the republic’s wealthiest members. Instead, they began casting the Senate as a protector of democracy, not an obstacle to it, because it could block transitory threats to the constitutional order upon which that democracy was built. Robert Byrd, a longtime Democratic senator from West Virginia, was among the chamber’s leading hagiographers in the late-twentieth century. His opening remarks to a new group of senators in 1996 sum up this mindset well.

Ladies and gentlemen, you are shortly to become part of that all-important “necessary fence,” which is the United States Senate. Let me give you the words of Vice President Aaron Burr upon his departure from the Senate in 1805. “This house,” said he, “is a sanctuary; a citadel of law, of order, and of liberty; and it is here—it is here, in this exalted refuge; here, if anywhere, will resistance be made to the storms of political phrensy and the silent arts of corruption; and if the Constitution be destined ever to perish by the sacrilegious hand of the demagogue or the usurper, which God avert, its expiring agonies will be witnessed on this floor.” Gladstone referred to the Senate as “that remarkable body—the most remarkable of all the inventions of modern politics.”

The Senate, in Byrd’s view, had long “provided stability and strength to the nation during periods of civil strife and uncertainty, panics, and depressions.” The attack on Capitol Hill is a perfect test for this idea. Here we had a president who had spent two months in vain and futile attempts to overturn the results of a free and fair election that he lost. At every turn, he had failed. And so he summoned his followers to Washington, told them that the country was in peril and that they had to fight for it, and directed them to march on the Capitol, where he would join them. He did not and retreated instead to the White House, where he would resist efforts to help the besieged lawmakers when the rioters broke down the doors.

Three weeks later, the Senate has indeed cooled down, as Washington predicted—but only on providing accountability for Trump’s role in inciting an insurrection against the Senate. Republican senators are now claiming that an impeachment trial would be too vindictive or too dangerous. Some argue that it would be unconstitutional to convict Trump now that he’s out of office, even though the Constitution says no such thing and most legal scholars disagree with this view. Indeed, if these naysayers were correct, then the Senate’s power to disqualify impeached officials from office would be meaningless—an impeached official could simply resign right before the vote.

I bring this up not because I particularly enjoy criticizing the Senate or those elected to it, but because it’s worth thinking about ways to make the chamber better—or, at the very least, less terrible. Filibuster reform isn’t vital just because it might help President Joe Biden pass some of his agenda, but because it makes Congress more responsive to the democratic process than to a hyperpolarized minority faction. Debating deeper reforms for the Senate isn’t important because constitutional amendments are possible anytime soon, but because Americans deserve a debate about the long-term health of their institutions. All the arguments for preserving the Senate in its current form are about to be disproven—not by the Senate’s many critics, but by the timidity of its current members.