In May 1987, Justice Thurgood Marshall delivered a speech at the annual seminar of the San Francisco Patent and Trademark Association. That year marked the two-hundredth anniversary of the Constitution’s drafting in Philadelphia, and celebrations were planned nationwide under the guidance of former Chief Justice Warren Burger, who had resigned from the court a year earlier to orchestrate the proceedings. But not everyone saw reason for patriotic rejoicing. As he did so often during his final years on the court, Marshall dissented.

“I cannot accept this invitation, for I do not believe that the meaning of the Constitution was forever ‘fixed’ at the Philadelphia Convention,” he told the audience. “Nor do I find the wisdom, foresight, and sense of justice exhibited by the Framers particularly profound. To the contrary, the government they devised was defective from the start, requiring several amendments, a Civil War, and momentous social transformation to attain the system of constitutional government, and its respect for the individual freedoms and human rights, we hold as fundamental today.”

Marshall’s own career was a testament to those changes. Even before joining the Supreme Court, he played a pivotal role as a civil rights lawyer in redefining and expanding the Constitution’s protections. “When contemporary Americans cite ‘the Constitution,’ they invoke a concept that is vastly different from what the Framers barely began to construct two centuries ago,” he said. Instead of celebration, he counseled a more humble and sober reflection on how Americans had fought, lived, and died to create the modern Constitution.

Marshall’s argument is even more relevant today. The past three decades, which span my entire life, have shown the limits and flaws of the Constitution of 1787. Congress is a pale shadow of its past self. Between partisan gerrymandering of the House and widening geographic disparities in the Senate, the two chambers can barely be called “representative” of the people they ostensibly serve. The average legislator, beholden to the demands of loose campaign-finance laws, spends more time dialing for dollars than crafting major legislation or overseeing the executive branch.

Generations of lawmakers ceded so much discretion to presidents that they are now effectively bystanders to de facto lawmaking by the executive branch. American governance now takes place through a new set of checks and balances: the presidency’s power to enact policy versus his opponents’ willingness to challenge it in court. Looming over everything is the Supreme Court, where conservatives have entrenched themselves as a near-permanent anti-majoritarian backstop. The 50-year project to impose a particular ideological vision upon the courts appears destined not only to imperil the high court’s legitimacy but also to place a hard ceiling on what government can accomplish.

Trump’s presidency is a case study in how these simmering problems can become urgent crises. Many of his cruelest immigration policies—including his decision last year to declare a national emergency so he could build a border wall that lawmakers refused to fund—can be traced to the discretion that Congress gave the executive branch. The Russia investigation showed the limits of the Justice Department’s ability to hold presidents accountable for potential criminal activity, and the Ukraine scandal saw his administration thwart even basic forms of congressional oversight through raw executive power.

Public opinion polls show that Americans largely favor legalizing marijuana, raising taxes on the rich, implementing universal background checks for gun purchases, and providing a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. But Congress is so broken and captured by right-wing ideologues and a self-interested donor class that it can’t hope to pass proposals that enjoy supermajority support. Without a functioning national legislature, Americans will find it far harder to confront the global recession around the corner and the long-term threat of climate change right behind it.

Past generations of Americans improved and repaired the Constitution by amending it piece by piece. But there is no single reform that can cure what now ails the republic. What’s required instead is a top-to-bottom overhaul of our basic constitutional machinery: how our lawmakers are elected, how our presidents exercise their immense power, and how our judges and justices are placed upon our highest courts. Even if these proposals do not ever become part of the nation’s basic charter, the question is still worth asking: What would it take to create a government that is more representative, more functional, and less corrupt than the one we now have?

THE LEGISLATURE

Most problems in American politics, even in the Trump era, can be traced to Congress and the structural woes that undergird the legislative branch. One of them is gerrymandering. In 2010, Republicans swept into power in the House and in state legislatures across the country in a conservative backlash to the Obama administration. Fortuitously for the American right, these victories coincided with the once-in-a-decade redrawing of legislative maps after the 2010 Census. Republican state lawmakers seized the opportunity to consolidate power at the state and federal level.

The results were startling. Though Democrats won a landslide victory in the 2018 midterms, an analysis by the Associated Press found that Republicans won 16 more seats in the House than their overall vote share justified. The AP also found that advantageous maps allowed the GOP to keep control of seven state legislative chambers that would’ve otherwise turned blue.

The Supreme Court has long held that the Constitution forbids racial gerrymandering, but demurred on whether courts could hear challenges to partisan gerrymandering. That changed last year: In Rucho v. Common Cause, the court’s conservative majority ruled that federal courts could not strike down legislative maps for excessive partisanship. (State supreme courts retain the power to strike them down, as Pennsylvania’s did in 2018.) The high court’s ruling effectively ended a decade of legal warfare over warped redistricting plans. It also left Americans with few options to remedy the problem.

Adding a “don’t gerrymander” clause to the Constitution would only invite endless litigation about what counts as gerrymandering. A more durable solution would be to elect House members through proportional representation. Under this system, each state would essentially count as one large House district. In the 2018 midterms, 4.1 million Texans voted for GOP House candidates, and 3.8 million Texans voted for Democratic House candidates. Thanks to gerrymandering, Republicans took 23 seats with 50.4 percent of the vote, while Democrats received just 13 seats with 47 percent of the vote. Under proportional representation, Texas Democrats and Republicans would have both received 18 House seats that year.

A virtue of this system is that it won’t inherently benefit any one party or coalition. If California’s House seats in 2018 had been allocated by the statewide vote total instead of by district, for example, Republicans would’ve carried 19 of the 53 seats instead of just seven. Not only would this make elections more competitive within each state, it would also result in a more representative mix of lawmakers in each state’s delegation.

The most dramatic effect would be on the political parties themselves. Americans are used to a system in which only Democrats and Republicans can win elections, especially at the national level. In countries with proportional representation, legislative seats are distributed to any party that reaches a certain threshold of the overall vote. That gives both voters and candidates more incentive to rally around smaller parties that better represent their views. Under such a system, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Nancy Pelosi, Justin Amash, and Jim Jordan might all belong to different political parties.

Other countries use a variety of methods to determine exactly which representatives are chosen for seats. Some use what’s known as a closed-list method, which lets voters cast a single vote for a party and then delivers to its candidates a number of seats equal to its vote share. Others use an open list, which allows voters to choose candidates from different parties.

Proportional representation would be a major departure from the framers’ vision for Congress. Many of them feared that the emergence of political factions would destabilize the young country. As a result, the framers largely failed to accommodate or anticipate the inescapable role of political factions in democratic governance. In the early republic, for example, some states elected their House delegations through general-ticket voting. That method allowed voters to cast a number of votes equal to the number of seats, which often meant that a single party could expect to capture all of the seats from that state. Congress abolished the method in 1842, when it passed a reapportionment act that mandated single-member districts for House elections.

Article One is largely the product of overlapping compromises among the framers. Large states secured a House of Representatives in which seats would be allocated among the states by population. Small states compelled the creation of a Senate, which granted each state two senators, regardless of size. Slave states and free states struck a bargain to count slaves as three-fifths of a person for representation, giving slave-owners a disproportionate level of influence in national politics until the Civil War. Rewriting Article Two to enshrine proportional representation would allow Americans to move past 200-year-old bargains and deals and establish a legislature that better represents today’s needs.

In some ways, the House is the easy part. The democratic deficit is far more acute in the Senate. In his book Why We’re Polarized, Ezra Klein notes that if current demographic trends continue, 70 percent of Americans will live in the largest 15 states by 2040. “That means 70 percent of America will be represented by only 30 senators, while the other 30 percent of America will be represented by 70 senators,” he wrote. Under the Constitution of 1787, the result will be a permanent veto power for a minority—currently constituted of white, rural Americans—over legislation from the House and nominees from the president.

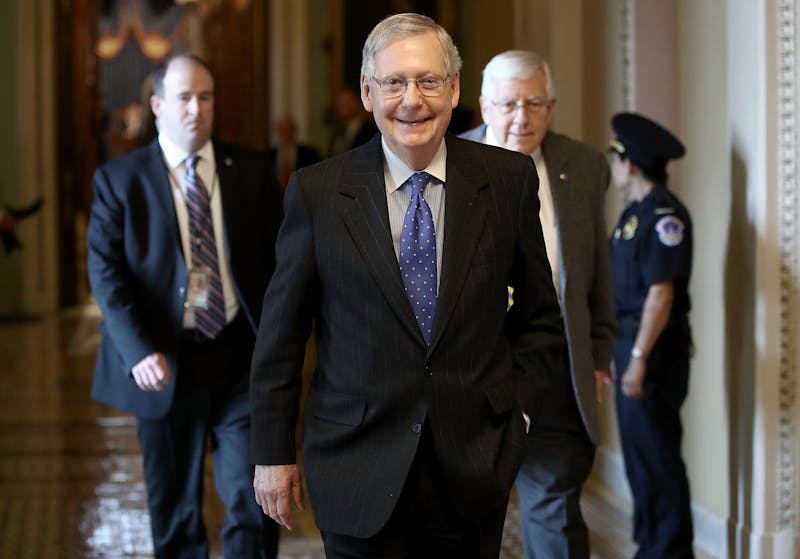

The framers intended for the Senate to counterbalance the majority’s will, and it has exceeded all their expectations. Senators from both parties have spent the last two decades using the filibuster to bring the chamber to a standstill. The world’s greatest deliberative body, as it is now only called in mockery, spends its days under Majority Leader Mitch McConnell ignoring legislation from the House and rubber-stamping judicial nominations sent by the White House.

The optimal reform would be to scrap the two-senators-per-state provision in Section Three of Article One of the Constitution. While the redesigned House will be better able to represent state interests, a redesigned Senate would become a forum to represent national interests. One hundred senators would still be elected to six-year terms, with one-third of the seats up for election every two years. But voters would instead select a closed list of senators to represent them in the upper chamber—meaning voters could only vote by party, not by candidate. Each party would then receive a number of seats roughly equivalent to its vote total. Proportional representation would break the rural stranglehold on the Senate while ensuring that it can still function as a protector of minority rights.

There’s a catch, however. The Constitution of 1787’s provision for amendments forbids any changes that would deprive states of equal representation in the Senate without those states’ agreement. That raises the threshold for amendments from the usual three-fourths requirement—a formidable 38 states—to unanimity. There’s an open debate among legal scholars about whether this barrier could be overcome by amending that provision at the same time. Either way, it raises the possibility that Senate reform could be blocked by just one state legislature.

If it can’t be altered, then the only way to cure the democratic deficit would be to strip the Senate of its powers over legislation. Senators would still give advice and consent to presidential appointments, approve or reject treaties, and serve as jurors for impeachment trials. But they could only vote to delay budget-related legislation for one month and all other legislation for up to one year. Britain adopted similar reforms for the House of Lords in 1911 to resolve a constitutional crisis after the chamber refused to approve a budget passed by the House of Commons. Though the House of Lords still exists and plays a role in the U.K. legislative process, it no longer serves as an obdurate barrier to the people’s will.

The last step toward reforming the legislature is to repair the damage inflicted upon Congress by the other two branches. Under Chief Justice John Roberts, rulings like Citizens United v. FEC and McCutcheon v. FEC sharply limited lawmakers’ ability to repair the nation’s campaign finance laws. Giving Congress the explicit power to regulate and prevent corruption in American elections would empower legislators to reduce the influence of money in politics. Trump’s impeachment trial also showed the limits of Congress’s ability to carry out oversight of the executive branch. By limiting the scope of executive privilege and giving lawmakers the constitutional authority to ask the courts to uphold subpoenas, a new Constitution could place the legislative and executive branches on an equal footing once more.

THE EXECUTIVE

Seven days after he took office in January 2017, Trump issued a sweeping executive order that banned almost all visa travel from seven Muslim countries. Three days later, Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates said that she would not defend the order in court. “At present, I am not convinced that the defense of the executive order is consistent with these responsibilities of the Department of Justice, nor am I convinced that the executive order is lawful,” she wrote in a letter to department employees. A few hours later, Trump fired her. The White House released an angry statement that night claiming that Yates had “betrayed the Department of Justice” and derided her as “an Obama administration appointee who is weak on borders and very weak on illegal immigration.”

It was the first salvo from Trump in what would become a three-year siege of the Justice Department. The president fought to overturn the post-Watergate consensus that the department and its leaders should maintain a degree of independence from the White House. He told associates that he wanted an attorney general who would favor his own political and personal interests, all while demanding that federal investigators probe and harass his political foes. Trump’s relentless—and ultimately successful—effort to tame the Justice Department means that future presidents will be positioned to take the same approach with more subtlety.

Trump’s allies in the conservative legal movement defended his actions by arguing that the Constitution established a “unitary executive” for the nation. Under this view, the executive branch’s powers reside entirely within the president; all other officials simply exercise them on his behalf and serve at his whim. Whatever the merits of this perspective, it’s become a staple of Trumpian rhetoric against limits on the executive branch.

Americans do not have to look far for alternative models. The presidency is already something of an anomaly in American governance. Maine, New Hampshire, and Tennessee elect only a governor; Alaska, Hawaii, and New Jersey elect only a governor and a lieutenant governor. Most Americans, however, already live under plural elected executives. They elect secretaries of state, attorneys general, treasurers, and a variety of other state officials on a regular basis. While enthusiastic champions of the unitary executive such as Attorney General William Barr might blanch at adopting that approach at the federal level, he cannot say it’s beyond the American constitutional experience.

There are instances in which a plural executive would be counterproductive at the national level, of course. If the federal secretary of state did not answer to the president, the United States would risk having multiple voices speaking for it in foreign policy. An independent secretary of defense may risk undermining the president’s role as the military’s top civilian leader. There are also circumstances in which a plural executive would be unnecessary. It’s doubtful that the fate of the republic will ever hinge on whether the president can dismiss the secretary of transportation, for example.

But there are two positions where a measure of independence is essential. One is the attorney general, who oversees the federal government’s legal affairs and supervises all federal investigations and prosecutions. The other is the secretary of the treasury, who oversees the executive branch’s finances and revenues. Barr used his position to frame the Mueller report in the best possible light for Trump, while pushing inquiries into the president’s preferred conspiracy theories. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin defied a subpoena from Congress to turn over the president’s tax returns to House committees, which sought to investigate his financial records for evidence of corruption and self-dealing.

The simplest solution would be to remove the president’s power to fire those officials. To ensure turnover, their terms would automatically end whenever a new president was sworn in. Presidents would still nominate a new attorney general or a new treasury secretary, the Senate would still approve or reject them, and Congress could still impeach and remove them from office. But those individuals would now have the freedom to ignore him without fear or threat of reprisal. While this may sound like a radical shift, it would merely constitutionalize the Justice Department’s de facto independence after Watergate and extend it to another vital branch of national government.

Finally, it’s long past time to abolish the Electoral College. Americans are well versed in the system’s flaws by now. It exists only to hand the presidency to someone who didn’t receive the most votes for it. Two of the last five presidents reached the White House after coming in second to their opponent. Millions of Americans are effectively locked out of the process because they don’t live in so-called battleground states, where the candidates devote most of their time and energy. All of these flaws benefit sparsely populated rural states, whose residents enjoy unearned influence in American politics because of a constitutional defect.

The only viable option is to elect the president by nationwide popular vote. From time to time, defenders of the Electoral College note that if three or more candidates receive large shares of votes, the popular vote could hand the presidency to someone who received only a modest plurality of the American people’s support. This paradox would be more troubling if there weren’t a simple solution for it. If no candidate receives a majority of the vote for president, a runoff election would be held between the top two candidates one month later to determine the winner.

Watergate was a bracing moment for Congress. Lawmakers saw firsthand how the executive branch’s vast powers could be abused, particularly when it came to law enforcement and intelligence, and how legislative oversight had broken down. They responded with a wave of reforms: the Freedom of Information Act, a wide range of civil-service reforms, a total overhaul of campaign-finance law, the creation of ethics watchdogs throughout the executive branch, and much more. Some of these reforms have proven more illusory than others. The Supreme Court, beginning with Buckley v. Valeo in 1976, slowly unwound Congress’s ability to regulate campaign contributions and fight public corruption.

Others have crumpled when directly challenged by Trump. Congress mistakenly assumed when it created the Office of Government Ethics, for example, that the president would be willing to punish federal employees like Kellyanne Conway, who hawked Ivanka Trump’s clothing line on national television. Trump added a signing statement to the March coronavirus stimulus bill suggesting that he would ignore its requirement that an inspector general regularly apprise Congress about how certain funds are spent. Though Democrats drew little attention to it, Trump’s actions in the Ukraine scandal even appeared to violate a 1974 law that placed limits on the president’s ability to block congressionally appropriated funds.

Indeed, one of the Trump era’s most important lessons is that American presidents are only bound by the rule of law as much as they want to be—or at least as much as a supermajority of the Senate is willing to stomach. An independent Justice Department and Treasury will help prevent some of these abuses. So will a strengthened Congress that is willing to use its existing oversight powers. But the new Constitution should also explicitly make clear what should never have been in doubt: The president is subject to criminal investigation at the state and federal level while in office, and he cannot pardon himself to escape accountability for his actions. In other words, the president is not above the law.

THE JUDICIARY

One area in which American politicians are actively contemplating major structural reforms is the Supreme Court. Trump’s appointments of Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh all but guaranteed a reliable conservative majority on the high court for the next generation. The immense stakes surrounding each Supreme Court confirmation battle have turned them into hyperpartisan nightmares. Kavanaugh’s confirmation, in particular, proved to be a toxic affair for the Senate, both parties, and the court itself.

The problem with the Supreme Court isn’t really a problem with the Supreme Court per se. What’s undermining the high court is the method by which its members are chosen. Presidential candidates are increasingly vowing to appoint justices with predetermined views or affiliations, weakening the court’s integrity. Members of the Senate Judiciary Committee either probe the nominee for any sign of constitutional heresy or laud them for their commitment to the rule of law—the approach depends on which party the senator belongs to and which party controls the White House.

The only way to fix the Supreme Court confirmation process is to end it. The president and the Senate would retain the existing process to nominate and confirm federal District Court judges and federal appellate judges, as outlined in Article Two of the Constitution. Under this proposal, Supreme Court justices would be instead chosen at random from sitting federal judges within each of the geographic circuit courts of appeal. There are currently 11 circuit courts of appeals, plus one for the District of Columbia. That would produce a court with 12 associate justices. A thirteenth seat would be held by the chief justice, who would be appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

This system would effectively end the judicial wars that have plagued American politics for the last five decades. It would expand the current court without resorting to partisan court-packing schemes, while removing any future threat of court-packing by fixing the Supreme Court’s size at 13 justices. Choosing future Supreme Court justices at random would spell the end of the conservative judicial-confirmation machine, as well as liberal attempts to build one of their own, and eliminate dark-money donors as an influential factor in the court’s makeup.

To ensure regular turnover, each justice would serve staggered 18-year terms on the high court. If a justice dies or retires, another judge from that seat’s respective circuit would be chosen at random to fill the remainder of the term. Once their 18-year term on the high court ends, the now-former justice would automatically return to his or her old position. (The chief justice could choose a judgeship in the circuit of their choice.) This method squares the circle between two worthwhile goals: imposing term limits upon the Supreme Court and protecting life tenure for all federal judges.

Under this system, senators would find it easier to reject flawed nominees because no single nomination would reshape American constitutional law or inspire intense partisan fervor. Justices would no longer feel obligated to retire under one president or avoid retiring under another. Americans, no matter their ideological leanings, would no longer be gripped by existential dread whenever one of the court’s members suddenly dies or receives a grim medical diagnosis. The macabre and unseemly discussions about the justices’ lifespans would become a thing of the past. And the court’s ideological makeup would no longer be determined for decades to come by a single electoral cycle.

There are drawbacks, of course. Using federal judges as the sole pool for new Supreme Court justices would exclude practicing attorneys, legal scholars, and state court judges who might otherwise make great justices. Some might fear that this method would deprive the high court of a broader set of legal perspectives among its members. There are two basic counters to these objections. First, presidents almost never nominate anyone other than sitting federal judges to the Supreme Court, so the loss would be more abstract than substantive. And second, presidents and senators could shun the risk of overly narrow nomination searches by casting a wider net for prospective federal judges in general. That would strengthen not only the Supreme Court but the lower courts as well.

THE STATES

In the Constitution of 1787, the United States is what its name suggests: a perpetual union of states with a limited federal government. Americans today are more familiar with a robust federal government than the framers had envisioned. When I began sketching out these reforms last year, I wondered if an updated constitution should take this condition into account, with the bulk of American governance formally transferred to the national level and state and local governments taking an even more limited role in political life.

Then the pandemic came. No electoral method or constitutional order can guarantee that the country will always be governed by those who place the national interest over their own partisan goals or personal agenda. Trump’s disastrous approach to the coronavirus pandemic will likely cost this country tens of thousands of lives at minimum and inflict economic and social damage beyond anything in living memory. His cascade of failures stands out even more sharply when compared with actions taken by state and local leaders in California, Ohio, Washington state, and elsewhere, whose actions helped flatten the curve and saved many of their constituents’ lives.

The juxtaposition between state and federal responses forced me to rethink my approach to American federalism. I cannot argue with a straight face today that the federal government should wield a greater share of the states’ allocated powers while it dramatically fails to show it could properly use them. At the same time, I still favor a strong federal government and an expansive reading of the Commerce Clause so that national solutions can be applied to national problems. And I cannot ignore that for most of the last quarter-millennium, it was the states that most often undermined Americans’ civil rights and restrained their right to democratic participation.

To that end, I would only offer three changes to the current balance of powers. First, I would strengthen a little-known provision of the Constitution of 1787 that never reached its full potential: the Guarantee Clause. The short proviso declares that the federal government “shall guarantee to every state in this union a republican form of government.” In other words, states could not become monarchies or theocracies or direct democracies; they had to adhere to small-r republican principles. In 1849, the Supreme Court ruled that this “guarantee” could only be enforced by Congress and not the courts. By allowing courts to hear challenges against state practices that violate the Guarantee Clause, Americans would gain another tool to challenge more subtle forms of state-level political repression.

Second, I would constitutionalize Section 1983. The provision, whose shorthand name comes from the portion of the U.S. Code in which it resides, comes from a Reconstruction-era law that targeted the original Ku Klux Klan and its allies. Section 1983 allows Americans to sue state and local officials in federal court for violating their civil rights under color of law. It is, at its best, a mighty weapon with which ordinary people can bring abusive police officers and authoritarian officials to justice. Over the past half-century, however, the Supreme Court has undermined its efficacy with a doctrine known as “qualified immunity,” which often amounts in practice to absolute immunity for all but the most egregious violations. Enshrining Section 1983 in constitutional text would restore one of the great safeguards of American liberty to its proper status.

Third, the new Constitution should explicitly state that the right to vote, once obtained by age or naturalization, cannot be deprived for any reason whatsoever. No American should have to spend another moment standing in line for hours at a polling place in Georgia, or have their voter registration canceled by an overzealous secretary of state in Ohio, or be denied the ability to participate in democratic life because they didn’t pay court fees in Florida. Constitutions exist to place certain questions beyond the simple reach of the democratic process—including, ideally, who gets to participate in that democratic process.

THE BILL OF RIGHTS AND IMPLEMENTATION

What about other constitutional rights? The states adopted the original Bill of Rights—the first 10 amendments of the Constitution—after the framers distributed the proposed Constitution to the states for ratification in 1787. Modeled after state bills of rights and similar protections elsewhere in the Anglo-American legal tradition, the amendments countered Anti-Federalist critiques that the new Constitution would be insufficient to protect Americans’ liberty. In the interest of continuity, the original 10 amendments would be kept unaltered.

But there would also be reforms to the process by which future amendments could be made. Once approved by Congress, a proposed constitutional amendment would be ratified once it received the assent of any number of state legislatures whose total population exceeds three-fourths of the national population. The task of redefining the scope of the American people’s rights would then more easily reside where it properly belongs: with the American people themselves, and no one else.

Adopting any of the measures I’ve outlined above, however, means using the existing methods at hand. Proposed amendments must currently pass a two-thirds vote in the House and the Senate or be demanded by two-thirds of state legislatures. From there, ratifying a proposed amendment requires the approval of three-fourths of the state legislatures—or, if Congress wishes it, three-quarters of state ratifying conventions instead. History shows how formidable these barriers can be: Congress has not sent a successful amendment to the states since 1971 or an unsuccessful one since 1978.

I have no expectation that any of the proposals I’ve outlined above will be ratified in my lifetime, let alone any time soon. If the system were healthy enough to readily adopt these changes, it might not need them. But hope is the point. I would like to live in a country where the candidate who receives the most votes becomes president, where lawmakers are answerable to voters instead of donors or gerrymanders, and where Supreme Court vacancies do not spark existential struggles for power. Until then, it’s vital to remember that our constitutional system doesn’t have to be this way, and that a better one is possible.