It’s democracy’s death knell: The feeling that the future is beyond us, the sensation that we’ve lost, as citizens, the ability to direct our lives together in a meaningful way. Sometimes it feels as though that power has been stolen. In other instances, it’s the sheer scale or complexity of a problem that outstrips our democratic capacity to manage it. Climate change, globalization, inequality, and now a pandemic—these challenges are dangerous for democracy because they make us feel less sovereign. Authoritarianism feeds on incapacity.

According to a new study from Freedom House, the coronavirus pandemic is accelerating the global crisis of liberal democracy as covetous autocrats take advantage of the emergency to expand their powers. But the opposite is also true. Democratic weaknesses have made the world’s Covid-19 response more difficult.

We’ve learned this year that civic health and public health are intimately and painfully linked. From the hollowing-out of local journalism to declining public trust and violent polarization, America’s preexisting conditions of democratic frailty have hamstrung its scientific experts and public health officials. When it finally, inevitably arrived, President Trump’s own Covid-19 diagnosis crystallized the toxic relationship between democracy and the pandemic, each making the other a worse version of itself.

We can flip this equation. For there is, amid all this, a generational opportunity for American citizens and their next president to reinforce democracy while saving lives. Careful and civic-minded messaging is the key. How leaders communicate about Covid-19—the words and stories they use to explain what is required and what to expect—can strengthen the sense of common purpose required to rise to this difficult, but not insurmountable, challenge. The president-elect should know that the right kind of Covid-19 messaging could heal the body politic in more ways than one.

This fall, we published a study analyzing the public health communications strategies used by nine democracies around the world in response to the pandemic. One of our discoveries was especially startling: Jurisdictions with the finest Covid-19 responses often emphasized solidarity and democratic citizenship in their public health messaging. In a range of relative “success stories,” from Taiwan and South Korea to Germany or British Columbia, we found leaders joining clear scientific information with emotional intelligence and repeated reference to democratic values.

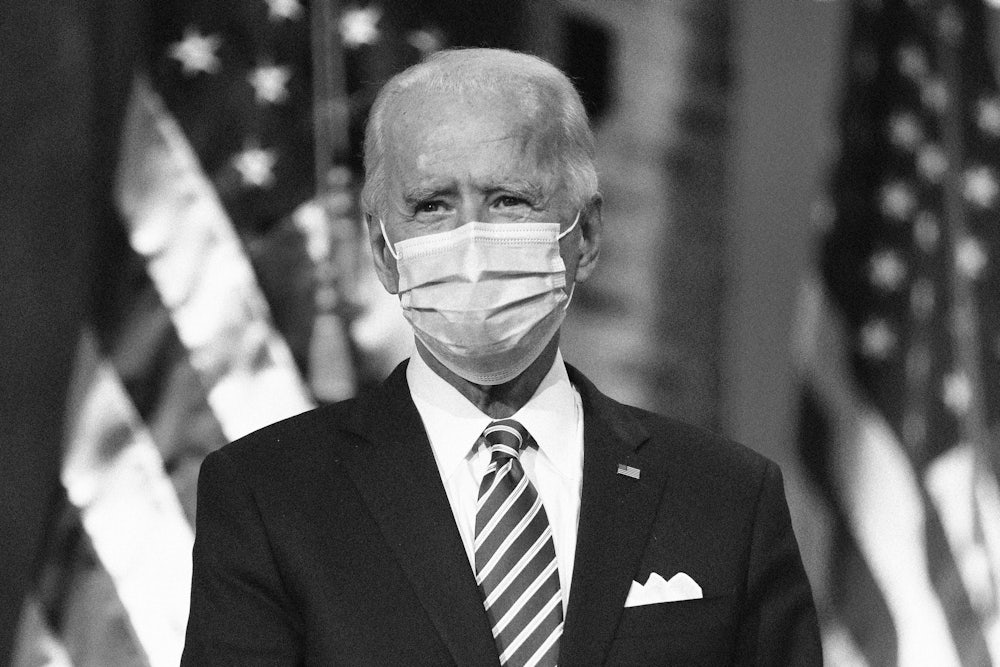

President-elect Joe Biden has already indicated that better communication will be a priority. He has pledged “consistent, reliable, trusted, detailed nationwide guidance” from a single reputable source as part of his strategy for a stronger Covid-19 response. Clarity, however, is only half the battle. By themselves, facts and clearly stated health measures can’t fend off fatigue, help people feel more invested in their neighbors’ welfare, or remind citizens that they are still sovereign, still in control of their shared futures. You can’t build solidarity with science alone.

Public health officials should be empowered to deliver clear scientific guidance—but once that hurdle is cleared, it will remain crucial for Biden and Vice President–elect Kamala Harris to explicitly articulate the ways in which Covid-19 is at once a challenge and opportunity for American democracy. This is what leaders have done in both Taiwan and South Korea, two jurisdictions with extremely effective Covid-19 responses as well as resilient democratic cultures. Taiwan’s digital minister, Audrey Tang, recently observed that Covid-19 “actually strengthened our democracy.” President Tsai Ing-wen has argued, “It is possible to control the spread of the virus without sacrificing our most important democratic principles … democracy is in our DNA.” Similar rhetoric has been deployed in South Korea, which held one of the world’s first pandemic elections in April—and broke turnout records in the process. Prime Minister Chung Sye-kyun noted that the country had “turned the crisis into an opportunity for democracy to mature.”

South Korea and Taiwan exemplify the democratic potential of public health in more ways than one. Contrary to popular belief, their Covid-19 success is owed not to “Confucian cohesion” but rather the democratic ability to learn from mistakes and make necessary course corrections. After struggling during the SARS outbreak in 2003 and MERS in 2015 with public compliance and confusing communications, both states reimagined their public health institutions with clearer chains of command and better messaging capacity. This, too, is an illustration of democratic power, the capacity for reinvention and renewal.

As frequently as they receive information about public health measures, citizens need to hear that they still possess, as individuals and as a people, the capacity to change the course of this pandemic—the abdication of certain Republican governors notwithstanding. Misinformation is a threat to both public and democratic health. But fatalism is no less lethal.

The Biden administration might look to the messaging of German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who has led an effective Covid-19 response even as the country’s swelling anti-democratic right kicks sand in the wheels. From the start, Merkel has affirmed that there is nothing inevitable about the pandemic’s course. At the core of her rhetoric lies the firmly stated conviction that Germans will determine the human and economic consequences of Covid-19 for themselves. “We are not doomed,” she explained in March, “to passively accept the spread of the virus.… We are a democracy. We live not by compulsion, but rather by shared knowledge and collaboration.”

Germany has recently reintroduced tough public health restrictions nationwide to deal with the pandemic’s second wave. Although Berlin’s Covid-19 response has been broadly supported by 85 to 90 percent of Germans, right-wing criticism of a “Covid dictatorship” is mounting. The chancellor appears to be taking this in stride. Speaking to the Bundestag on October 29, Merkel admitted that the pandemic was a “severe test” for German democracy. But she also said that a robust, reality-based public debate about the course to be taken would strengthen the country’s democratic fabric. “How things proceed is in our hands.”

The democratic potential of health messaging is clearest when we turn to the most explosive Covid-19 flashpoint in the United States: individual autonomy. Polarization has made it seem to Americans that anarchy (freedom) or strict lockdown (tyranny) are the only alternatives. Not so in places like British Columbia or Sweden, where leaders combined relatively wide latitude for individuals and businesses with clear principles for making tough ethical decisions during the pandemic. These strategies were not perfect, and both jurisdictions have suffered second waves worse than the first. But public trust remains high. Even as additional restrictions are introduced, officials continue to prioritize autonomous decision-making.

Good messaging has been the linchpin of these strategies. Rather than seeking to regulate or issue guidance for all social behaviors, officials in these jurisdictions have mostly trusted the public to make good decisions—and, most importantly, gave them the tools to do so with clear communications. Especially in British Columbia, government messaging has reinforced consistent and useful principles for safe socializing: staying physically distant, wearing masks, keeping gatherings small, and meeting outdoors when possible. Effective communications in these territories have allowed citizens to keep as much individual autonomy as possible while encouraging them to feel more responsible for and invested in the collective Covid-19 response.

After months of their unnerving absence, many of us have learned that clear and consistent public health communications are no luxury. They are a necessity. But thoughtful messaging strategies can do much more than save lives. Framing the pandemic as a challenge to be met by a democratic people, rather than a tragic inevitability, could leave Americans feeling more trusting than before, more resilient than before, and more sovereign than they did before the pandemic hit. No Senate majority is required for the next president to seize this opportunity.

More than many realized, public health depends on clear, compassionate, and civic-minded communication. Even more surprising is that the health of American democracy might, too.