Fossil fuel interests have long argued that environmental rules kill jobs. Not having such rules, though, kills people. And that’s particularly clear when it comes to the coal industry.

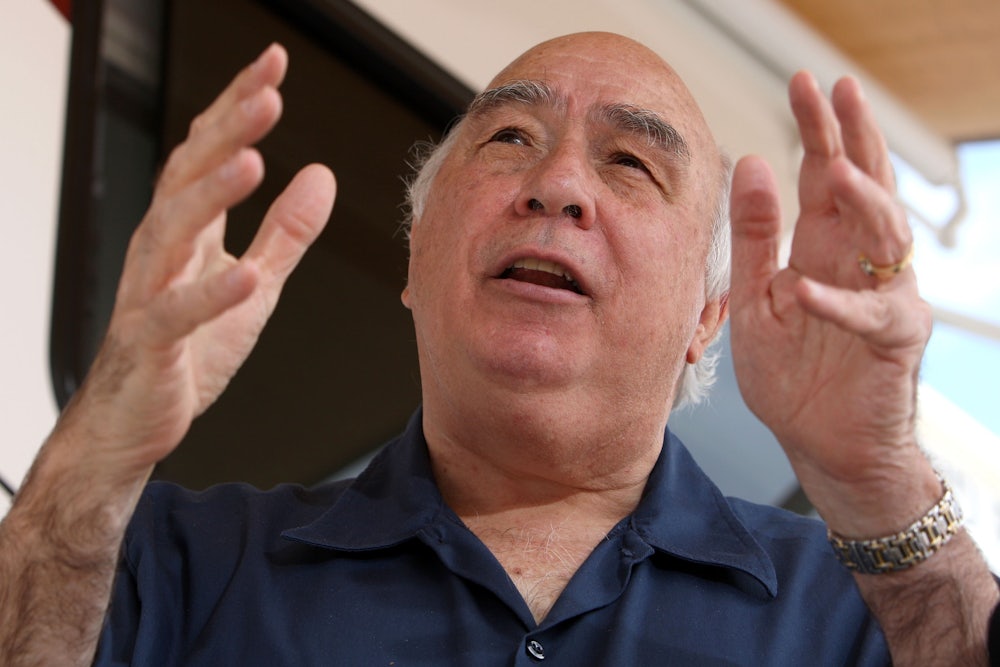

Bob Murray, the 80-year-old coal baron who fought against safety and environmental regulations that would affect his mining empire, presided over several deadly mining disasters, and sued people who pointed that out, died this weekend. In the last years of his life, Murray—whose coal company was the eleventh to file for bankruptcy during the Trump administration—waged a fierce battle against anything that might alleviate black lung, a painful, incurable disease, also known as coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, that affects a tenth of veteran coal miners in the United States. Last month, Murray filed an application with the U.S. Department of Labor for precisely the kind of black lung benefits he’d fought paying into for years. Last fall, he had conversely told NPR that his respiratory ailment didn’t have “anything to do with working in the coal mines.” An exact cause of death has not been announced, though in 2016 Murray was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, another lung disease common among coal miners.

As black lung cases ticked upward in 2014, Murray filed a lawsuit against the Obama administration over a regulation curbing coal dust in underground mines, claiming that the rule intended to protect employees from irreversible lung scarring would cost the company billions. Weeks after Trump’s inauguration, which he helped fund, he handed the new administration an “action plan” that included calls to gut the Mine Safety and Health Administration and revise the “arbitrary” coal dust rules he’d been battling for years. He also pleaded for a federal bailout that would keep him from having to pay for health care and pensions of retired United Mine Workers of America miners; like many other coal barons, he attempted to shirk such obligations in bankruptcy court.

After reviewing Murray Energy’s bankruptcy filings, several of its creditors alleged that Bob Murray and his family had treated the company as a personal “piggy bank,” awarding themselves exorbitant pay amid layoffs. Murray took home $14 million in one year as the company’s debts mounted. During the same period, The New York Times reported, he earmarked $1 million for climate denial outfits like the Competitive Enterprise Institute and Heartland Institute. As the company navigated bankruptcy, it spent $100,000 in the first quarter of 2020 lobbying to—among other things—further slash the 50 cent excise tax on coal mined underground that funds the Black Lung Trust Fund. Justifying its ongoing assault on the tax, the National Mining Association cited hardships imposed by a pandemic respiratory illness that puts miners afflicted with black lung at higher risk of death. (Industry lobbyists had already succeeded in cutting the excise tax down from $1.10 per ton in 2018 and slashed the one on surface mining down to 25 cents.)

Murray repeatedly put what his company owed mine workers onto the government’s tab instead. Murray owed as much as $155 million to fund worker disabilities and treatment under the Black Lung Act but had put up just $1.1 million in collateral. When Murray Energy emerged from bankruptcy this summer as American Consolidated Natural Resources, the settlement declared that ACNR wasn’t responsible for claims against Murray under the Black Lung Benefit Act. Its $74.4 million worth of liability under that law was shifted to the Department of Labor’s Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, established under the BLBA.

Murray Energy had also been the last major contributor to the 1974 UMWA Pension Plan, providing what is often the sole source of income to some 92,000 miners and their families. Not long after Murray Energy filed for bankruptcy, Congress—under pressure from the UMWA—agreed to keep the fund solvent to preserve health care benefits for 13,000 miners. Murray wasn’t alone in trying to socialize the debts of his flailing company and privatize the rewards. In a Stanford Law Review article published just before Murray Energy’s and other high-profile coal bankruptcies, researchers Joshua Macey and Jackson Salovaara found that four of the country’s largest coal producers had used bankruptcy to shed $5.2 billion of employee and environmental obligations between 2012 and 2017.

Murray consistently rallied resources toward electing politicians who would keep him from having to pay anything more than the bare minimum to the people who built his fortune. Watchdog groups have raised questions over whether Murray coerced salaried employees to donate to Murray Energy’s Political Action Committee, which donated $1.4 million to almost invariably Republican politicians between 2007 and 2012. “We have only a little over a month left to go in this election fight,” one internal memo Murray sent out to employees, reported by The New Republic, warned. “If we do not win it, the coal industry will be eliminated and so will your job, if you want to remain in this industry.” A Murray foreman later sued over what she alleged was a wrongful firing after she declined to give to the Murray Energy PAC.

Murray frequently required miners to attend Republican political functions, where they would serve as political props, including for Donald Trump. He bussed miners up to Washington, D.C., to support EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt during his Senate confirmation hearing in 2017, as well. Rounding out an illustrious career, Murray was also sued by two female employees in 2019 for sexual harassment. And he waged brutal legal battles against his critics in the media, including a well-publicized spat with Last Week Tonight host John Oliver for daring to point out that the 2007 Crandall Canyon collapses that killed nine people were probably caused by Murray Energy safety violations and not, as Murray had claimed, an earthquake. As news of Murray’s death spread on social media Monday, the song Oliver had dedicated to the coal baron recirculated as well: “Eat Shit, Bob.”