IT IS BOTH a pundit’s truism and a mathematical reality that Mitt Romney’s path to the White House runs through Ohio. And that path, in turn, runs through a firm called Murray Energy.

Over the years, CEO Robert Murray has brought in GOP pols from as far away as Alaska, California, and Massachusetts for fund-raisers. In 2010, the year John Boehner became House speaker, the firm’s 3,000 employees and their families were his second-biggest source of funds. (AT&T was in first place, but it has nearly 200,000 employees.) This year, Murray is one of the most important GOP players in one of the most important battleground states in the country. In May, he hosted a $1.7 million fund-raiser for Romney. Employees have given the nominee more than $120,000. In August, Romney used Murray’s Century Mine in the town of Beallsville for a speech attacking Barack Obama as anti-coal. This fall, scenes from that event—several dozen coal-smudged Murray miners standing behind the candidate in a tableau framed by a giant American flag and a COAL COUNTRY STANDS WITH MITT placard—have shown up in a Romney ad.

The ads aired even after Ohio papers reported what I was told by several miners at the event, a bit of news that an internal memo confirms: The crowd was not there of its own accord. Murray had suspended Century’s operations and made clear to workers that they were expected to attend, without pay. “I tell ya, you’ve got a great boss,” Romney said in acknowledging Robert Murray from the stage. “He runs a great operation here.”

The accounts of two sources who have worked in managerial positions at the firm, and a review of letters and memos to Murray employees, suggest that coercion may also explain Murray staffers’ financial support for Romney. Murray, it turns out, has for years pressured salaried employees to give to the Murray Energy political action committee (PAC) and to Republican candidates chosen by the company. Internal documents show that company officials track who is and is not giving. The sources say that those who do not give are at risk of being demoted or missing out on bonuses, claims Murray denies.

The Murray sources, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution, came forward separately. But they painted similar pictures of the fund-raising operation. “There’s a lot of coercion,” says one of them. “I just wanted to work, but you feel this constant pressure that, if you don’t contribute, your job’s at stake. You’re compelled to do this whether you want to or not.” Says the second: “They will give you a call if you’re not giving. . . . It’s expected you give Mr. Murray what he asks for.”

And what he asks for offers a lesson for 2012: Even in a year of hyperventilation about super PACs, dubious older ways of raising political dollars still matter.

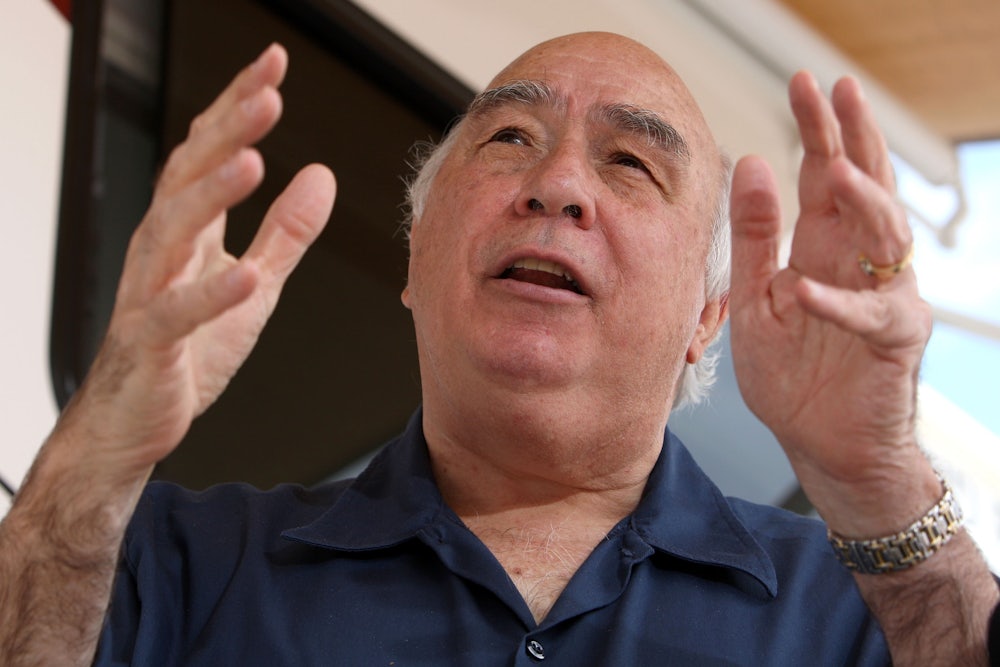

BOB MURRAY, WHO is 72, is a legendary figure in Appalachian coal country. He hails from three generations of miners in southeastern Ohio; his father was paralyzed in a mining accident when Bob was nine. Murray himself has been injured while working below ground. Unlike his forefathers, though, Murray became a suit. He won a scholarship to study mine engineering and eventually rose to chief executive of North American Coal. In the late 1980s, he took out personal loans to start Murray Energy, which has grown to own eight mines in six states. It is the largest privately held coal-mining concern in the country.

Like a lot of mining executives, Murray’s a ferocious critic of federal mining regulations—even after the 2007 collapse at his Crandall Canyon mine in Utah, where nine people died. He also knows how to throw his weight around. In 2001, he sued the Akron Beacon Journal for $1 billion after a critical profile; that same year, he was acquitted of assault charges after allegedly throwing an environmental activist against a wall. In 2002, local media reported that he warned off mine safety inspectors with this line: “Mitch McConnell calls me one of the five finest men in America, and the last I checked, he was sleeping with your boss,” referring to Labor Secretary Elaine Chao, the senator’s wife. (Murray denied the account.) Murray’s fiery streak was on full display after the Crandall Canyon collapse. Wearing his trademark sweater-vest, he angrily insisted to reporters that the collapse had been caused by an earthquake—scientists disagreed—and railed against efforts to curb carbon emissions. At one point, he pulled back his collar to show the scar from his mining accident.

In southeastern Ohio, Murray’s dominance evokes an earlier era. Miners at the Century event told me he treats them well and aspires to know all their names. But the paternalism also features some unmistakable messaging. A huge sign draped outside Murray’s Powhatan No. 6 Mine—the only unionized facility among Murray’s properties—reads: SAVE EASTERN OHIO: FIRE OBAMA. At Century, a lobby notice tells employees where to call to order yard signs with the slogan STOP THE WAR ON COAL: FIRE OBAMA.

The message apparently gets through. Since 2007, employees of Murray Energy and its subsidiaries, along with their families and the Murray PAC, have contributed over $1.4 million to Republican candidates for federal office. Murray’s fund-raisers have feted the likes of Scott Brown, Rand Paul, David Vitter, Carly Fiorina, and Jim DeMint. Home-state pols get love, too. Murray’s PAC and staffers are the sixth-largest source for Ohio senatorial hopeful Josh Mandel. They’ve given $720,000 to candidates for state office in the past decade.

Internal Murray documents show just how upset Murray becomes when employees fail to join the giving. In missives, he cajoles employees to attend fund-raisers and scolds them when they or their subordinates do not. In cases of low participation, reminders from his lieutenants have included tables or spreadsheets showing how each of the eleven Murray subsidiaries was performing. And at least one note came with a list of names of employees who had not yet given. “What is so difficult about asking a well-paid, salaried employee to give us three hours of his/her time every two months?” Murray writes in a March 2012 letter. “We have been insulted by every salaried employee who does not support our efforts.” He concludes: “I do not recall ever seeing the attached list of employees . . . at one of our fund-raisers.”

Here’s what stubborn employees missed: The events are typically at Undo’s, an Italian restaurant and banquet hall in St. Clairsville. Dinner is pasta and salad. There’s a cash bar. There’s a receiving line. There are speeches by the visiting beneficiary who generally extols coal. (Employees in Ohio also get invitations to fund-raisers near Murray’s southern Illinois mine; they’re not expected to attend, but are encouraged to send checks.)

The ritual becomes expensive for Murray’s engineers, surveyors, and accountants. “People are very upset about being constantly asked for the checks, because people have lives and families and expenses,” says the first source, a political independent. “They say, ‘This isn’t right. . . . I don’t think they’re allowed to do this.’ Most people do it grudgingly.”

Those who decline, the source says, prepare to be questioned. “When they’re pressuring people to write checks, if they haven’t by the deadline, you hear people making excuses—I just had to repair my car, I had an unexpected bill, I just had to pay tuition.”

And yet the tin-cupping continues. “I am asking you to rally all of your salaried employees and have them make their contribution to our event as soon as possible,” Murray writes in a letter to managers ahead of a 2011 fund-raiser for Mississippi Senator Roger Wicker and Tennessee Senator Bob Corker. “Please see that our salaried employees ‘step up,’ for their own sakes and those of their employees.”

A September 2010 letter lamenting insufficient contributions to the company PAC is more pointed. “The response to this letter of appeal has been poor,” Murray writes. “We have only a little over a month left to go in this election fight. If we do not win it, the coal industry will be eliminated and so will your job, if you want to remain in this industry.”

The pressure to give begins as soon as employees enter the company, the Murray sources say. At the time of hiring, supervisors tell employees that they are expected to contribute to the company PAC by automatic payroll deduction—typically 1 percent of their salary, a level confirmed by a 2008 letter to employees from the PAC’s treasurer. (That letter also assures employees that they would not be “disadvantaged” by not giving.) Employees are given a form to sign, explaining that the giving is voluntary. “In the interview . . . I was told that I would be expected to make political contributions—that [Murray] just expected that,” says the first source. “But I was told not to worry about it, because my bonuses would more than make up what I would be asked to contribute.”

Later, the sources say, Murray sends letters to employees’ homes asking them to give to specific candidates. The letters feature suggested amounts depending on their salary level—one middle manager was encouraged to give $200 to then–Oregon Senator Gordon Smith—and include forms to fill out and return, with checks, to Murray headquarters. The letters come with great frequency. Before the 2008 election, there were nine fund-raisers in less than three months. Guests included then–New Hampshire Senator John E. Sununu, then–Alaska Senator Ted Stevens, and Oklahoma Senator James Inhofe.

Murray’s exhortations demonstrate more attention to ideology than to Strunk & White. In August 2011, Murray urged employees to attend a $2,500 fundraiser for Rick Perry, “likely to be the Republican Nominee to defeat the destructive Barack Obama.” And for the unconvinced, he attached a “brief, partial listing of the destruction that Barack Obama has reeked.” Murray employees and their households came through, becoming Perry’s second-largest source for funds in the entire country.

After Perry dropped out, Murray switched to Romney. In his April letter for the fund-raiser the next month, he told employees, “America needs business and job creation, not the ruthless destruction that we are seeing from Barack Obama and his Democrats supporters, whom are Hollywood characters, liberal elitists, radical environmentalists, unionists, and Americans who do not want to work.”

IN THE AGE of Citizens United, there’s something a bit quaint about political giving via a corporate PAC or from donations rustled up from workers. But the structure still holds appeal. While a CEO could simply write a huge check to a candidate’s super PAC, urging employees to give not only avoids drawing undue attention to the boss, but it also provides an appearance of broader support for the candidate and offers that candidate more control over the funds.

Murray Energy general counsel Mike McKown says the firm’s approach to political giving complies with federal laws. Employees are not required to give to the PAC, he says, nor are they reimbursed. “We follow carefully the FEC [Federal Election Commission] rules about what employees can be solicited and how they can be solicited,” he says, adding that Bob Murray’s encouragement for employees to contribute to individual candidates is the CEO’s personal endeavor. “The PAC and Mr. Murray’s fundraising are kept separate,” he says.

So how does that comport with the memos urging division heads to get their underlings to pony up or the spreadsheets letting foot-draggers know that the company’s keeping track of who’s not giving? “It’s my understanding that the employees are encouraged to give, and he is enthusiastic about people giving contributions,” McKown says. “As far as utilizing internal company assets to further his company fund-raising, that’s all done within FEC guidelines.” There is no punishment or reward related to fund-raising, McKown says. “I’ve never ever seen people pay any consequence for giving or not giving to this PAC or events.”

McKown says the two sources who suggest generous employees get bigger bonuses are just wrong. “It’s Mr. Murray’s view of what the employee’s contribution was to the company that month,” he says.

The law around employee political contributions has its gray areas. The bottom line, says Paul S. Ryan, senior counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, is that employers can’t reimburse donations and the “folks running a corporate PAC cannot make a contribution to that PAC a condition of employment.” But the tricky thing in many cases is that a boss’s enthusiastic suggestion comes across as something more. An authorization form does not necessarily get an employer off the hook, he says. “It can’t involve twisting arms.”

The Murray pressure, the sources say, extends to contractors as well. “They have to write big checks or they don’t do business with Murray Energy,” the first source explains. “They see it as an investment, as the cost of doing business,” says the second source, a lifelong Republican. One Murray vendor who is also a big GOP donor paints a less sinister picture. “Bob Murray’s no different than if it was the Democratic or Republican Party—they’re always encouraging you to support their candidates,” says Jimmy Phillips, the co-owner of Phillips Machine Service, where employees have given nearly $400,000 this election cycle. “We are very free to do what we want to.” McKown also says there’s no there there: “The letters that go out to vendors are the same as the ones that go to employees—they say, ‘Give what you can, if you can.’ ”

It’s not surprising that some of those with whom I spoke after Romney visited the mine said they had no problem with the contributions. Shawn Ray, a former general manager of Murray’s surface-mining operation, cast the spreadsheets as “just a competition amongst the guys,” not a sign of pressure. “It was so you know how you do against the other companies. The pressure to give is not so much for the company to give; it’s so we’re doing our part. It’s sort of personal for us.”

Others were more wary about discussing the fund-raising. After the rally, a veteran Murray engineer told me that “they like for you to [participate]. It’s not a requirement, but they like you to go.” When I asked him how he was able to afford the contributions, he gave a taut smile. “That’s enough,” he said.

On the rope line after the rally, I sought out Murray as he greeted his workers. I asked the CEO why so many people had turned out for the rally. “They’re frightened,” he said. “They’re afraid for their jobs and their livelihoods. They’re frightened, and I’m frightened for them.”

Alec MacGillis is a senior editor at The New Republic. This article appeared in the October 25, 2012 issue of the magazine.