Late in Homegoing, the debut novel by the Ghanaian-American writer Yaa Gyasi, a character named Marcus is introduced. Marcus is getting a Ph.D. in sociology at Stanford University, and—as happens—is struggling to decide what to write his dissertation about. He wants to study the convict-leasing system in the United States that essentially re-created the conditions of slavery for many African Americans in the South, including his own grandfather, but he feels the story cannot begin or end there. “How could he talk about Great-Grandpa H’s story,” he thinks, “without also talking about his grandma Willie and the millions of other black people who had migrated north, fleeing Jim Crow?” Further still, “if he mentioned the Great Migration, he’d have to talk about the cities that took that flock in. He’d have to talk about Harlem.” Marcus extrapolates further, until he sees no way to complete the project without also including the crack epidemic of the 1980s, the war on drugs, racial disparities in policing, and the way his very presence in the Stanford University library made others uncomfortable.

The moment reads as a guide to Homegoing itself. That novel is daringly expansive, its structure eschewing the idea that the story of Black people could be contained within a single generation or moment. It begins in eighteenth-century Ghana with the story of two half sisters, Effia and Esi. Effia, married off by her stepmother to a British officer, lives a life of luxury in the Cape Coast Castle, the infamous slave-trading fort that millions of Africans were trafficked through before boarding ships bound for the Americas. Esi is one of those enslaved Africans; when we first meet her, she is being held in the castle’s underground dungeon. The novel follows the next seven generations; we see Effia’s line live through the Anglo-Asante wars, respond to the advent of cocoa farming on the Gold Coast, and tangle with the reality of African complicity in the slave trade. Esi’s descendants in the United States endure the failed promises of Reconstruction, flee Jim Crow as part of the Great Migration, witness the Harlem Renaissance firsthand, and later become enveloped in the heroin epidemic of the 1960s.

This transatlantic epic was Gyasi’s effort to work through her own sense of disconnectedness from African American identity. In an op-ed for The New York Times titled “I’m Ghanaian-American. Am I Black?,” Gyasi explains, “I had been brought up to see myself as set apart from what my family called ‘black Americans,’ who stood a rung below what my family called ‘white Americans.’ Neither group was something you wanted to be.” It was in college that she first learned the word diaspora. Reading Chinua Achebe alongside Toni Morrison, she began the process of reconnecting for herself the dots between Africa and Black America through literature. The result was a novel that, though refreshingly ambitious, tended to under-develop its characters, imbuing them with more history than personality at times. Particularly in its ending, Homegoing did little to complicate the idea of diaspora, a concept fraught with tension since its inception. In Stuart Hall’s famous essay on diaspora, he warned against seeing identity as something “taking us back to our roots, the part of us which remains essentially the same across time.” We should instead, Hall encouraged, recognize that “identity is always a never-completed process of becoming,” always in flux.

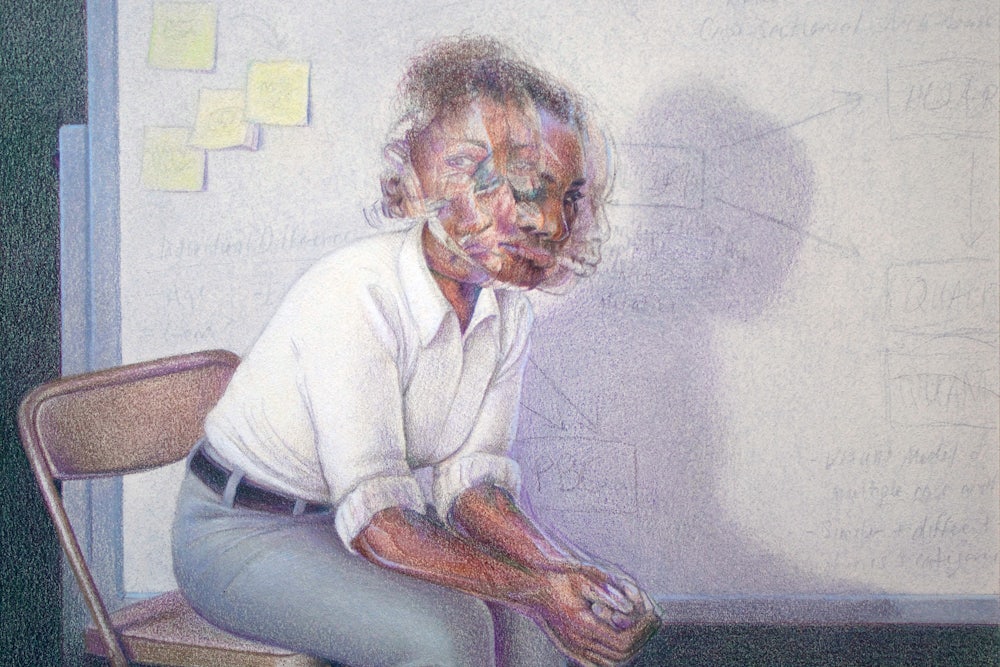

In scope and feel, Transcendent Kingdom is Homegoing’s opposite. Where Homegoing was grand, magical, and expansive, Transcendent Kingdom is earthy, grounded, and small; it is as if the two books should trade titles. The new book focuses on a single character, Gifty, who like Gyasi is the daughter of Ghanaian immigrants who settled in Huntsville, Alabama. When we meet her, she is in her sixth year of a Ph.D. in neuroscience at Stanford University, where she studies “the neural circuits of reward-seeking behavior” by getting mice addicted to the dietary supplement Ensure. Her brother Nana, we learn, succumbed to addiction when she was just a teenager, but this fact, Gifty insists, has nothing to do with her choice of study. This insistence becomes the central tension of the novel.

If Gyasi’s first novel was obsessed with roots, now she gives us a character who is made deeply anxious by the suggestion that her past or her family history should define her. Gifty, in essence, resists the very principles that governed Homegoing. The question here is how we bear witness to shared realities while avoiding the traps of stereotype. Animated by this wariness, Transcendent Kingdom is less a search for origins than it is a study of origin stories and the ways they can be wielded against people, particularly ones who grew up poor and Black.

Transcendent Kingdom begins with the arrival of a guest from home. One morning, Gifty gets a phone call from her mother’s pastor back in Alabama. “I think it’s happening again,” is all he says. In response, Gifty lets her mother come stay with her in California. From the moment they meet at the airport, we sense this mother-daughter cohabitation could prove difficult. While Gifty and her mother do not come to blows or have knockdown arguments, her mother essentially sleeps through the rest of the novel, unable to get out of bed. It is soon revealed that after Nana’s overdose and death, her mother fell into a deep depression, and started to abuse sleeping pills.

Her mother’s sudden presence intensifies the meaning of Gifty’s work, conducting research on addiction, even as she tries to deny it. The question—how did you get interested in science?—is the novel’s antagonist. Gifty resents the idea that her work is a project of redemption, for either her brother or herself, and Transcendent Kingdom exudes a bone-deep exhaustion with having to explain one’s background. Sad origin stories seem to Gifty little more than grist for fitting one’s life into a neat arc for others’ consumption. When she confides in friends about her brother’s addiction, they are quick to juxtapose the tragedy of Nana’s death with her own academic success. In college (at Harvard), a lab mate responds to the story of her brother with a burst of enthusiasm. “This would make such a good TED Talk,” she tells her, adding: “Seriously, Gifty, you’re amazing. You’re like taking the pain from losing your brother and you’re turning it into this incredible research that might actually help people like him one day.” Gifty resents it, but does not know how to escape it. That is, after all, what she is doing.

In her research, there’s a tacit desire to separate addiction from root causes, particularly social ones. Medicine, for Gifty, is a way of understanding spontaneously occurring phenomena and mutations; she consciously frames it as a way of disconnecting addiction, including her brother’s, from any existing social conditions or upbringing.

Any time I talk about my work informally, I inevitably encounter someone who wants to know why addicts become addicts. They use words like “will” and “choice,” and they end by saying “Don’t you think there’s more to it than the brain?”

Nana’s addiction started after he injured his ankle playing high school basketball and was prescribed opioids for the pain. Gifty bristles at the notion that his eventual dependence on the painkillers can be explained by the family’s financial struggles or the racism they experienced in Huntsville. “I know what my family looks like on paper,” she reflects. “I know what Nana looks like when you take the bird’s-eye view: black male immigrant from a single-parent, lower-middle-class household. The stressors of any one of those factors could be enough to influence anhedonia.” To see addiction this way, Gifty says, is to relegate it to certain sectors of society, and to permit the white and financially secure the illusion they can escape it. But most of all, she resents the way this thinking reduces her brother to just a member of a demographic, rather than a whole and complex human. “There is no case study in the whole world that could capture the whole animal of my brother.” In focusing on the brain and its pathways, Gifty feels she is not only working toward a cure for addiction, but also that she is freeing addicts from the narratives others try to foist on to them.

The kind of research that Gifty’s ex-boyfriend Raymond and his friends conduct at Stanford roils her. They are part of the university’s prestigious Ph.D. program in cultural studies, Modern Thought and Literature, in which Raymond works on protest movements. His friends “speak about issues like prison reform, climate change, the opioid epidemic, in the simultaneously intelligent but utterly vacuous way of people who think it’s simply important to weigh in.” In frustration, she wonders, “What is the point of all this talk? What problems do we solve by identifying problems, circling them?” She is irritated by their desire to find deeper meaning in her own scientific research. When she describes her mice research to them, she says:

“... Like even the idea of a ‘you’ that can restrain ‘yourself’ doesn’t quite get at it. The brain chemistry of these mice has changed to the point where they aren’t really in control of what they can or can’t control. They aren’t ‘themselves.’”

They all nodded vigorously, as though I’d said something extremely profound, and then one of them mentioned King Lear.

Gifty sees in science a kind of refuge from all of this.

In these kinds of conversations, there is a desire for cause and effect, a need to get to the bottom of things, to trace a problem back to its starting point. In her own work, Gifty is fascinated by the potential for isolation. A new technique called optogenetics allows researchers to use light “to target particular neurons, allowing for a greater amount of specificity” than previous methods, where treatment of one cell could negatively impact neighboring ones. She finds peace in the literal ability to apply a laser focus to a problem. She craves this kind of exactitude in her own life, for her brother’s addiction to exist as itself, having nothing to do with the people who were closest to it. It is a coping mechanism that does not last long.

There is in Gifty an impatience with symbolism, something the novel connects with her upbringing in an evangelical Christian community. At Harvard, she attends a church service where a progressive minister asks if the Bible is supposed to be taken literally. “When I was a child, I would have said yes, emphatically and without a moment’s thought,” Gifty says. “What I loved best about the Bible,” she explains, “particularly the outlandish moments in the Old Testament, was that thinking about it literally made me feel the strangeness and dynamism of the world.” The literal interpretations of the Bible that defined her religious community in Alabama are a salve for her, a place in the world where things could be what they were, not what was read into them. In college, she leaves a spoken-word show because a poet refers to God as she. This freeness with interpretation goes against the basic tenets of faith “that ask you to submit, that you accept, that you believe, not in a nebulous spirit, not in the kumbaya spirit of the Earth, but in the specific. In God as he was written and as he was.”

It is that same yearning that guides Gifty, that desire to be as she is, not interpreted, not a symbol for something bigger, not a representative of all Black women or people with a family history of addiction. It is an understandable longing, but comes with a certain degree of erasure of the very community that might help sustain someone through those processes. It is part of the conundrum that fascinates Gyasi throughout Transcendent Kingdom—how to bear witness to shared experience while maintaining autonomy and individuality.

Eventually, the ferociously guarded Gifty capitulates. She confides in her lab mate Katherine about her mother’s condition, about her brother, about her religious upbringing, and the journal she used to address to God “about how we got here.” When Katherine asks her why she is so embarrassed, Gifty makes a “sweeping gesture” to the room—“Look at my world. Look at the order and the emptiness of this apartment. Look at my work. Isn’t it all embarrassing?” The source of her embarrassment is hard to parse—it is certainly more than the simple juxtaposition of a bygone religious fervor with the quiet sterility of her graduate student apartment. There’s a broader sense of bewilderment that her life before bears so little resemblance to one she leads now, and perhaps this embarrassment over having departed so drastically from her origins is in fact something more akin to shame. Despite a change in scope, in Transcendent Kingdom Gyasi is still plumbing the questions that guided Homegoing. Gyasi has returned to her roots, and they run deeper now.