Joni Culver was born in Iowa in 1970 and raised by a mother who felt, at times, isolated by a farm life spent cooking and cleaning. At seven, asked as part of a second-grade project to name a potential career, the future U.S. senator offered three—Nurse, Farmer’s Wife, and Miss America. By the time she was a high school junior in Coke-bottle glasses and braces, Miss America seemed a less plausible outcome, and Joni was unduly grateful for the attention of a classmate who soon became her boyfriend. When this boyfriend hit her in front of her friends, she made excuses for him. When she was accepted to Iowa State, he was displeased, and when she returned home during her second semester, he raped her. Joni joined the ROTC. It was in this capacity that she met Gail Ernst, a divorced Army supervisor 17 years her senior. When they married, she followed him to Savannah, Georgia, where she sold women’s shoes at a mall. While her husband was overseas, she told him she was pregnant, and when the ultrasound technician told her she was having a girl, she worried he would be very disappointed.

They moved back to Iowa, and Joni joined the National Guard. She was promoted in 2002, the only woman officer. Male officers found her presence disconcerting. “I’m sorry,” one told her later. “I just didn’t know how to mentor a woman.” In 2003, when her daughter was still a toddler, she was deployed for a full year to Kuwait, where her unit was charged with trucking missiles and mail and mattresses to the front. A commander from another battalion repeatedly came on to her; there was no one to whom she could report him. A group of troops hung around the female shower trailer, taking pictures when a door opened. When she—a captain—told them to stop, they ignored her. Back in Iowa, her service as a lieutenant colonel in the National Guard was low-status within the military, which ate at her. She found that when she tried to tell war stories to her husband, he interrupted her to share stories of his own. He joked about killing his ex.

What does it mean to be a Republican woman running for office in 2020? There are currently 13 Republican women in the House. There are 16 Republican House members named “Michael” or “Mike.” More Republican women than ever before are running, but they face such improbable paths to elected office that in November their numbers will improve only slightly, if at all. This is largely because the party apparatus does not support them. “On the Republican side, there is this misconception that it is somebody’s ‘turn,’” said Julie Conway of VIEW PAC, a political action committee that exclusively supports Republican women, “and there are a lot more guys in the state House or Senate or mayors of towns waiting for the congressmen to retire than there are women.” “Unless all the cards are falling right for you,” said Jennifer Lim, founder of the nonprofit Republican Women for Progress, “there will be someone else the party is running, usually an old white guy named Greg or Mike, or maybe a young white guy named Greg or Mike.” But it’s bleaker than just a sclerotic system intent on perpetuating itself, because Republican primaries involve Republican voters. A survey conducted by Republican Women for Progress found that 71 percent of Republican voters do not think the current number of women in Congress to be a problem, which is simply to say voters do not see electing more women as a worthwhile goal. When she was head of recruitment for the National Republican Congressional Committee, New York Representative Elise Stefanik recruited 100 Republican women to run. Ninety-nine of them lost.*

Given their numbers, Republican women have little power, as a bloc, in Congress. They get less credit when they speak out against the president, and are criticized more when they fall in line, a rule to which this profile is no exception. Republican women must appear feminine, but not too feminine, and while they must overcome the mundane sexism of any popularity contest, they cannot generally appeal to gender as a source of competence, which would be seen as playing identity politics. The Republican women running in 2020 have a certain sheen, as if they have just walked off set. They are asked to be everything at once; “Mother, Soldier, Leader,” reads Joni Ernst’s web page, though traditional Midwestern motherhood and concurrent military service are presumably in tension. It is harder to get Republican women to run, and when they do, the opposition spends more, on average, to defeat them. Democrats are in fact spending millions to replace Iowa’s junior senator with first-time candidate Theresa Greenfield, and it may work; as of late August, Greenfield and Ernst are tied. Joni Ernst is a woman fighting to keep her seat at a time when women are abandoning her party en masse, among colleagues for whom recruiting women is not a priority, appealing to voters for whom the scope of acceptable female identity is contracting.

A county auditor is an elected position for someone who keeps the county’s books. At a 2003 budget meeting in Montgomery County, Iowa, tension over budgetary matters was sufficiently high that the sitting auditor, 50-year-old Connie Magnuson, appears to have punched the county supervisor, a 52-year-old woman, in the shoulder. (Magnuson’s lawyer claimed it was a “tap.”) According to Ernst, the GOP approached her husband and her mother while she was overseas to ask whether she might run for auditor against Magnuson. This kind of tale is typical of Ernst, whose self-mythology involves a woman clean of ambition rising to power by doing a series of favors for other people. Ernst won, removed the deadbolts and security cameras her paranoid predecessor had installed in the office, and by all accounts ably defused the drama surrounding the job. While she was working, Ernst came to believe, her husband was having an affair with their daughter’s babysitter. Standing on the landing of the stairs in their home in Red Oak, she confronted him, at which point, according to Joni, Gail grabbed her neck, threw her down, and pounded her head into the floor.

U.S. senator from Iowa is not a job that becomes available with great frequency. When Democrat Tom Harkin announced that he would not seek reelection in 2013, he had been serving for 28 years, all of them as a junior senator to Chuck Grassley, who had been serving for 33. The dull white lawyer in line for this job, the foregone conclusion, was Democrat Bruce Braley, a congressman whom Harkin had mentored. Meanwhile, the low-stakes Republican primary was a sadly comic microcosm of the party we would come to know three years later. Candidates included Matt Whitaker, whose “masculine toilet” would come to light during his also-comic stint as acting attorney general of the United States; Sam Clovis, who would later be under investigation for colluding with Russia to interfere in the 2016 election; and a former energy executive named Mark Jacobs, who seemed, in 2014, to be the kind of capable, business-minded candidate Iowans could be expected to elect. According to Ernst, who was by that point a state senator, people kept asking her to run, too—a farmer in church, locals in town, a colleague in the state Senate—and so she deferred to their judgment. This apparent demand for an Ernst candidacy did not reach very far. Four months before the election, 74 percent of Republican adults in Iowa were not familiar with her. But it was Ernst who attracted the attention of David and Charles Koch, and Ernst whom they invited to an exclusive Koch networking event in Albuquerque. Soon she had her own shadowy PAC, Trees of Liberty, traceable back to the Kochs, which spent its money attacking Jacobs.

The connection that would most matter to Ernst’s campaign would be to a Republican strategist named Todd Harris. Harris filmed Joni in a neighbor’s barn in a plaid shirt and a thick outdoor vest, an outfit too crisp for the farm and too casual for the boardroom. She reads as feminine, but not soft. Her teeth are perfect, her short hair practical and dated, the hair of someone who does not care to keep up and will not make you feel bad for your own failure to do so. “I’m Joni Ernst,” she says, smiling. “I grew up castrating hogs on an Iowa farm. So when I get to Washington, I’ll know how to cut pork.” Jump cut to a squealing hog, three words with hard stops: Mother. Soldier. Conservative. “Washington’s full of big spenders. Let’s make ’em squeal.”

The ad is remarkable in its ability, within the space of 30 seconds, to weave together disparate, conflicting associations circling the Republican id: motherhood, the military, rural life, austerity, red meat, white working-class authenticity, and a kind of winking womanly aggression. Crucially, the ad was easy to mock, which liberals reliably did. Within 72 hours, the ad, a $9,000 project that did not run with any particular frequency in Iowa markets, had been viewed on YouTube 400,000 times. Ernst’s political identity was now that of a conservative who speaks truth to power; a farm-strong rural woman willing to take down the elites who make rules for rural men. If Joni Ernst had been trying to fit in, she would not have centered her campaign on pig castration. The campaign released a second ad, in which its leather-clad candidate, “a lieutenant colonel who carries more than just lipstick in her purse,” rolls up to a shooting range on a Harley, loads a gun, and fires. Joni had short-circuited some sexist impulse, found a way to avoid the trade-off between femininity and strength. “It’s like whoa, nobody’s going to push her around,” Sarah Palin told Iowans at an Ernst fundraiser. In pink text on a backdrop behind her: “Heels on, gloves off.”

It has never much mattered that outside this persistent branding effort, Ernst is not good at projecting authenticity. In interviews, she has a kind of stunned polish, as if steeling herself for attack. Her answers are scripted, safe, oft-repeated talking points devoid even of the small personal flourish of most media-shy politicians. There is no easy back and forth, no thinking aloud or rapport building. “Well, and, again…,” she begins many of her answers, unable to sound anything but irritated as she inevitably reverts to script. Even much later, in an interview about her marriage in which she is overcome with grief, her words remain distanced from the immediacy of her emotion, as if she is failing at a task she has assigned herself. It is also unclear, possibly even to herself, what Joni Ernst believes. In interviews, former colleagues in Iowa describe her as “coachable” and “packaged,” words that deny her agency in her own rise to power. There is sexism in this, but there is also the difficulty of identifying a single issue on which Ernst appears willing to break with both voters and the party.

In her 2014 primary, Joni, massively outspent by the front-runner, came from behind and easily won, at which point she was again the underdog. Democrats promptly dug up Facebook posts in which Gail Ernst called Hillary Clinton a “lying hag,” joked about shooting an ex-wife, and claimed that Janet Napolitano’s Department of Homeland Security was hoarding ammunition to prepare for civil unrest. (“And am I suppose [sic] to give up my guns?” Gail wrote. “As if! Traitorous skank!”) “I’m appalled by my husband’s remarks,” said Joni Ernst in a statement. “I’ve addressed this issue with my husband, and that’s between us,” though of course the statement itself confirmed that it was not.

Because Joni was not the chosen one, the male lawyer mentored by the sitting senator, she could not rely on the same chains of validation. “There were a lot of Republican operatives who didn’t take her seriously for a while,” said Conway of VIEW PAC. “She worked extremely hard. When a guy is running, men talk to each other. ‘Have you heard about Bob Smith? He’s fantastic.’ Now all the guys love Bob Smith. Joni had to spend so much more time proving herself to individuals than guys do. And she did it.” One would assume that working this hard would involve a touch of the ambition to which Joni will not admit, but there is also the drive to be taken seriously by an audience she presumes underestimates her. “My fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Sundberg, was my greatest advocate,” she writes in her memoir with a kind of sweetly bruised pride. “When I took the Iowa Basic Skills Test, she rushed to tell me that I scored in the 95–99 percentage range for all Iowa students, and she was jumping up and down, hugging me.”

As this stellar test taker knocked on doors, tape emerged of Braley deriding farmers at a private event. It was similarly helpful to Joni, castrater of swine, that he had publicly complained about the lack of “towel service” in the Senate gym. And so the first woman elected to federal office from Iowa ascended to the Senate, where pants on women were not allowed until 1993 and the pool was male-only until 2011—and where, she says, at her own swearing-in ceremony, Joe Biden addressed her husband as “Senator,” before instructing him to build a fence around the house to keep boys away from their daughter. When she told Gail about volunteer opportunities for senatorial spouses, he said he “wasn’t about to hang out with a bunch of women.” He rarely came to D.C. He called her, in conversation, a “feminazi.” He accused her of “going out with men” when she had meals with colleagues.

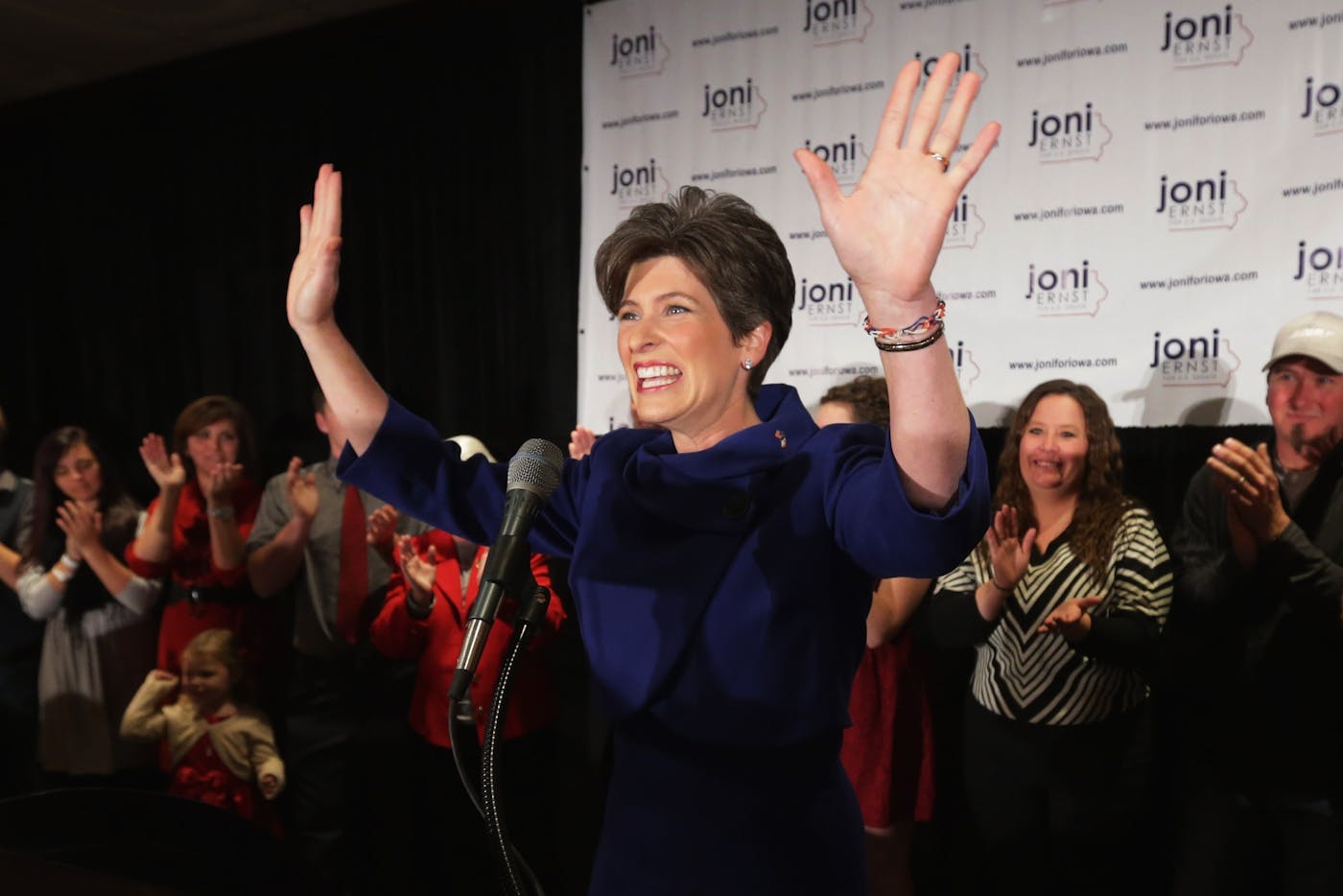

He was right to fear that she was outgrowing him. Joni Culver Ernst, perpetually underestimated, must have felt a sense of liberation as she moved her things from Iowa to D.C. She had grown up on a farm, attended a state school, come to power without the connections of most of her colleagues. She was young and fresh and attractive and poised, and she had won against terrific odds. She was asked to deliver the response to President Obama’s State of the Union less than a month after she arrived, which is to say that in four years she had gone from “Montgomery County auditor who doesn’t punch people” to the face of the Republican Party. She had overcome a rape, an alleged assault, the disdain and insecurity of her own husband, and she had outcompeted men with more resources and experience. She was putting space between herself and her marriage, and, in another sort of story, the best would be yet to come.

“Growing up,” Joni Ernst told Americans in January 2015, after Obama’s penultimate State of the Union, “I had only one good pair of shoes.” On display here was that robotically smooth delivery, that ability to float above whatever bad-faith monologue she happens to be delivering. Here too was that slightly exasperated pose of womanly maturity. She had gone to Washington, after all, to clean up the mess the men had made of it, those “big spenders” who had failed at the basic task of household budgeting. “On rainy school days, my mom would slip plastic bread bags over [my feet] to keep them dry. But I was never embarrassed. Because the school bus would be filled with rows and rows of young Iowans with bread bags slipped over their feet.” Iowans might note that she got the mechanics of the bread bag situation wrong (“insane,” “ridiculous,” and “you would soon develop a hole in the bag” are responses I got when I asked a group of older women from Joni’s hometown); the fact was you put bags inside your old, hole-ridden boots, not over your shoes in place of boots, as Joni maintained. But the bread bag comment (#breadbags) prompted the kind of mocking tweets Joni had always used to her advantage.

If there was embellishment around the edges, there was a truth at the center of the brand: Joni Ernst really was a farm girl who had castrated hogs. (“I’ll never forget the slimy feel of the testicles as I reached in and yanked them out,” she wrote later.) She had convinced voters that she was antagonistic to elites while doing precisely nothing to antagonize them, and she may well have been able to keep walking this tightrope under the relatively stable presidency of a Clinton or a Cruz. In Congress, she used her position to introduce a series of anodyne bills with names such as the “Global War on Terrorism War Memorial Act” or “A bill to designate the facility of the United States Postal Service located at 615 6th Avenue SE in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, as the ‘Sgt. 1st Class Terryl L. Pasker Post Office Building.’” Chuck Grassley called her “a good Republican senator,” and being good came with rewards. By 2019, she was one of two GOP women on the Judiciary Committee and the vice chairman of the Senate Republican Conference.

While in D.C., Ernst maintained, she went through her husband’s email and found that he’d been having a long-standing affair with a high school sweetheart. It was he who asked for the divorce from his far more successful wife; she could not convince him otherwise. And so they divided up their Harleys and their guns, their Hyundai and Explorer and Corvette, and he moved to Punta Gorda, Florida, with his girlfriend. Gail reportedly denied having an affair, accused her of her own, and sued, incredibly, for alimony. In court records, Ernst claimed that Donald Trump had asked her to be considered for vice president, but that she had withdrawn her name. “I continued to make sacrifices and not soar higher out of concern for Gail and our family,” she wrote. Soar higher, was the claim; the implication being that for 26 years he had pinned her down.

She had intended these details to be private, but when an Iowan alt-monthly discovered the documents, it appeared that Gail had failed to have them sealed. Her allegation of physical abuse was now national news, alongside the fact that she had withdrawn from consideration for the vice presidency. (Gail Ernst did not address the claim of physical abuse in news reports from the time.) After a tour of a hospital in Iowa, reporters asked her a series of questions about the divorce filings. She gave, at first, her usual clipped, careful, repetitive answers, but as reporters pressed, she seemed to run out of talking points. “I wanted those documents to be sealed, I think both of us did,” said Ernst, as if she were describing something very unpleasant and very far away. “I was now forced out as a survivor, and I think every survivor should have the right to decide when it’s their time to tell a story”—and here, her voice began to break—“and when it’s not their time to tell a story, and unfortunately that was taken away from me.”

Ernst would learn, over the following 18 months, how to talk about her abusive marriage, the vocabulary and the syntax of an experience that has been processed and made useful. But as she learned to talk about the experience of abuse, it was inconvenient that she was constantly called upon to defend Donald Trump. Her strategy, in dealing with a party leader accused by 25 separate women of sexual misconduct, was sometimes to distance herself verbally, but rarely to attract attention to herself by drawing a clear line of disagreement. She was careful. Asked about the Access Hollywood tape, she said she was a “realist” who “did not trust Hillary Clinton,” though one would imagine she might feel a certain kinship with a hardworking woman forced to answer for a man’s chaos.

Ernst had been called a “breakout star” the day after her election. Trump was not the kind of leader who made it possible for stars to break out. She was asked about a domestic abuser on Trump’s staff (“you can’t justify that,” she said of Trump’s response), and she was asked about Trump responding to a rape allegation with the words “she’s not my type,” and she was asked about tax returns. In 2019, she went viral not for a folksy speech about pig cutting or bag wearing but because she had been cornered at a community center in Templeton, Iowa.

“Where is the line?” asked Amy Haskins, a mother of seven, in oversize flannel with sunglasses perched on top of her head, a look that would appear very real when the clip caught fire, an outfit in which one could, say, ride a Harley or castrate a pig. She wished to know why the president was asking international leaders to investigate Joe Biden when southwest Iowa was underwater, crops were going unsold, and she could not obtain health insurance given a fibromyalgia diagnosis. “When are you guys going to say enough?”

Ernst avoided eye contact and scribbled some mysterious notes on a pad. She was in a blue blazer—not leather, not a warm, farm-ready vest—the prim clothes of a senator on tour.

“You still stand there silent, and your silence is supporting him, and not standing up.... You didn’t pledge an oath to the president. You pledged it to our country.” Ernst gave a long answer on preexisting conditions, and trailed off, but Haskins pressed for an answer to the question about Trump.

“OK,” said Ernst, looking like a woman stuck in an unpleasant customer service experience. “So, President Trump. Um.”

She shook her head and put a hand up, like, what can you do?

“I can say yay nay, whatever, the president is going to say what the president is going to do. It’s up to us as members of Congress to continue working with our allies....”

“I beg your pardon,” said polite Amy Haskins, “but all of our allies? He is pushing aside, he’s making fun of them on Twitter. He calls them names—”

“Well, and, ma’am—I—,” tried Ernst.

“Oh and we love people from North Korea, or we love Russia—”

The senator pursed her lips and raised her eyebrows and settled in to wait.

“It’s a nonanswer answer, and I understand,” said Haskins, sounding as if she genuinely did understand, but also she was going to keep talking.

“I can’t speak for him,” said Ernst. “I can’t speak for him!”

“I know you can’t speak for him, but you can speak for yourself.”

“And I do.... North Korea, not our friend! Russia, not our friend!”

“And what about whistleblowers?”

“Whistleblowers should be protected…. Laws need to be enforced.”

“Yeah, but we’re not hearing it from….”

“That’s because our media’s not covering those issues.”

“You have to say it for our media to cover it.”

The interrogation goes on, 12 minutes of Amy Haskins gently, persistently pressing on power, against the instinctual conflict aversion that afflicts the average Iowan. Fox News reported on the encounter, as did The Washington Post and The Guardian. The clip was played on CNN, which sent a correspondent to Iowa to inquire once again whether it was appropriate for the president to ask a foreign power to investigate a political rival, “yes or no?” In reply, Ernst, shaking her head, said, “Well, again, I think we’re going to have to go back, just as I said last week. We’ll have to wait, all of that information is going to go to Senate Intelligence”—a reply that CNN’s correspondent, echoing Haskins, called a “nonanswer answer.”

These deflections are an embarrassment, especially for a candidate sold as a steely straight-talker. Her practiced deference to the president did not ensure a swift or particularly generous federal response when August’s freak windstorm tossed trees into homes. Ernst’s approval ratings are down, and Iowa’s first woman to congressional office may well be its first one-term senator in decades. In June, Ernst was trailing Greenfield by 3 points. Greenfield released an ad in which she strides by a barn while reminiscing about working on her parents’ farm. She wears a plaid shirt and a thick outdoor vest, an outfit too crisp for the farm and too casual for the boardroom. She reads as feminine, but not soft.

This summer, Ernst released a political memoir titled Daughter of the Heartland, centered on the chauvinism she has encountered and overcome, and from which many of the episodes related here are taken. In that memoir, which details sexist encounters with Joe Biden and Chuck Schumer and Ted Cruz and National Guard officers, the president’s character is summed up as “good listener.” Given only this document, it would be fair to conclude that the president is a patient, benevolent feminist. This is not to say that Daughter of the Heartland is a standard political memoir; it is a series of vignettes about abusive relationships, and the emotional valence it registers will be familiar to many women. There is, for instance, the feeling of deliverance that follows a bad relationship, the sense that finally, one is free to move unencumbered, to stop mopping the mess that follows in the wake of an embarrassing, needy, careless, abusive narcissist. “I wouldn’t have to make excuses for my inappropriate husband anymore!” she writes of her divorce, a moment when it must have been possible to forget that she was heading toward an election year, a rush of relief before she recalled she would spend it making excuses for another man entirely.

* This story originally mischaracterized New York Representative Elise Stefanik’s role at the National Republican Congressional Committee in 2018.