At the start of 1873, Leo Tolstoy was fresh from the success of War and Peace and aware that the world was expecting an equally monumental work of art, something that would match that book (he refused to call it a novel) in historical scope and philosophic profundity. As such, he was consumed with writing a primer to teach Russian children the alphabet. He was sure it would be his legacy. “My proud hopes are these,” he wrote to a friend, “that two generations of all Russian children, from those of the tsar to those of the peasants, will learn using only this primer, and they will get their first poetic impressions from it, and that, having written this primer, it will be possible for me to die peacefully.”

Perhaps it was this obsession with letters, the beauty of their shape and the world of possibilities encoded in each one, that can explain the curious second proposal scene between Kitty and Levin in Anna Karenina (she rejected his first) in which the two communicate using just the first letter of each word they want to say. “He wrote the initial letters, w, y, a, m, t, c, b, d, t, m, n, o, t,” and Kitty understands intuitively that Levin is asking her. “When you answered me, ‘that cannot be,’ did you mean never or then?” Only t, only “then” it turns out, to Levin’s great happiness. In Creating Anna Karenina, Bob Blaisdell does not make this connection between Tolstoy’s work on the alphabet book and this scene from the novel, but it is the type of parallelism between the great Russian author’s life and art that interests him.

A professor of English at the City University of New York (Kingsborough), Blaisdell learned Russian in order to read the Anna Karenina novel in the original (after having first reread the novel in the English translation upwards of 20 times). The work of a Tolstoy superfan rather than a Tolstoy scholar per se, Creating Anna Karenina is an informal and chatty effort to understand what Tolstoy was up to in the four years he spent composing the novel. As it turns out, Blaisdell tells us, he was drinking copious amounts of “koumiss” (fermented mare’s milk) to stave off tuberculosis, penning vociferous calls for agrarian reform, learning Ancient Greek with the help of a priest, and trying to find a governess to tend to his growing family. The latter situation had gotten particularly desperate; Tolstoy wrote to a friend begging for references. “Nationality is of no matter: German, French, English, Russian—as long as it’s European and Christian. Salary—everything I can give.” Blaisdell wonders if Tolstoy had this stress in mind when he decided to open Anna Karenina with the story of a house torn to pieces by a governess’s dismissal (though of course in the novel it happens under more adulterous circumstances).

It is a big stretch, and Blaisdell knows as much, but his book is more of a playful experiment than a strict study. In its study of the comings and goings of the Tolstoy household at the time of the novel’s composition, Creating Anna Karenina asks if one of the world’s greatest novels was in fact just as much a product of everyday minutia—like who stops by for a visit with what kind of gossip to tell—as it was the culmination of long-simmering ideas about morality and desire. The result is a work in many ways more instructive about the creative process than about Anna Karenina specifically, a consideration of how distractions, familial interference, and side projects resulted in Tolstoy writing one of the world’s greatest novels.

The inspiration behind the character of Anna Karenina is widely considered to be a 37-year-old woman named Anna Stepanova, who worked as a housekeeper for one of Tolstoy’s neighbors. She and her husband regularly argued about his flirtations with governesses. Finally, she became so consumed with jealousy that she threw herself under a train but not before sending off a letter addressed to her husband, which reportedly read, “You are my killer; you will be happy with her if murderers can be happy. If you want to see me, you can view my body on the rails of Yasenki.” As the family knew the woman well, Tolstoy personally went to observe the autopsy; his wife wrote to a friend that he “was terribly shaken. He had known Anna Stepanovna as a tall, stout woman, Russian in face and character, a brunette with grey eyes, not beautiful but attractive.” The episode happened in 1872, just a year before Tolstoy first sketched out the character of Anna Karenina, who likewise had gray eyes.

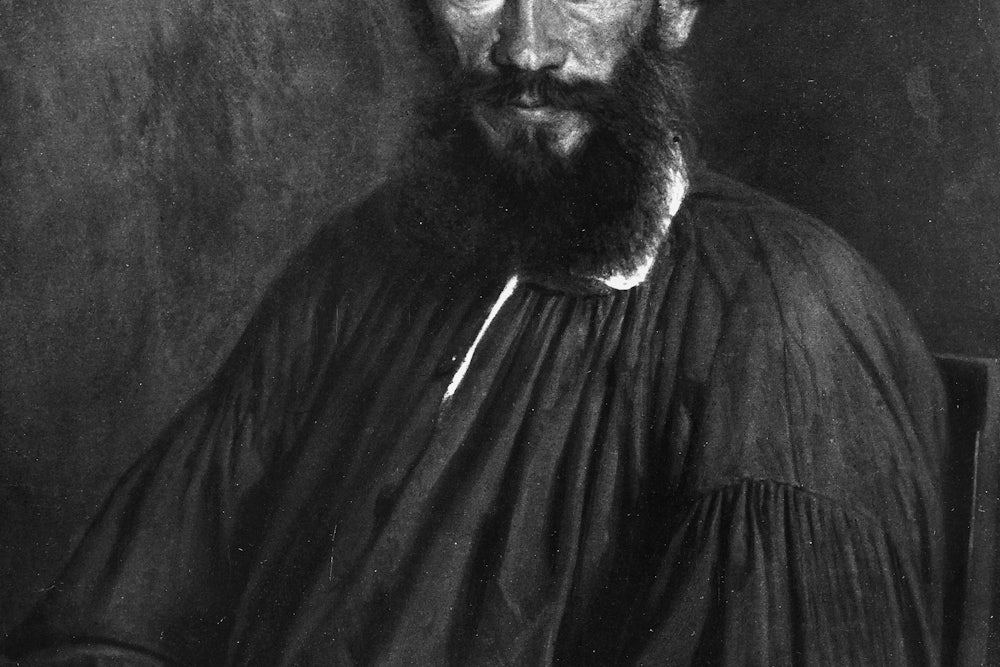

In March of 1873, Tolstoy told his wife, Sophia, that he had written a page-and-a-half and was “pleased with it.” She assumed he was referring to the major book he had been planning to write about Peter the Great, a fitting historical epic to follow War and Peace. Before this revelation, Tolstoy had been struggling greatly to write. “My work is not moving” he wrote his friend, the poet Afanasy Fet. To another, he complained, “Everything has been arranged so as to distract me: acquaintances, hunting, a court session in October with me as a juryman, and then the painter,” the latter referring to the portrait artist who had been sent to Tolstoy’s estate to paint him on behalf of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

The artist, Blaisdell writes, did however prove useful in offering some gossip from the capital. Anna Suvorina, the wife of a prominent publicist, was shot to death in a hotel in Saint Petersburg by a young man who had been in love with her. After killing Suvorina, the young man took his own life. The press was transfixed by the story as it combined society gossip with a crime of passion, and it all unfolded in one of the capital’s glitziest hotels. Tolstoy, too, was fascinated when he heard about it from the portraitist and asked a friend to send him “any details of the murder.” Blaisdell sees the episode as an example of Tolstoy’s growing fascination with suicide: Tolstoy’s editor, Mikhail Katkov, soon afterward lost a brother to suicide, and in his conversion memoir, A Confession (1881), Tolstoy admitted that he too had contemplated ending his own life around this time. Linking these stories with Anna’s suicide (and her lover Vronsky’s attempt to do so), Blaisdell identifies a larger epidemic of suicides that was sweeping the country, a symptom of a deeper, collective depression rather than just the result of a single love affair gone awry. Indeed, the failures of Tsar Alexander II’s reforms to lead to meaningful change had blanketed Russian society of the 1870s with a sense of disorientation and dread. In the next decade, Alexander II would die at the hands of a suicide bomber.

Blaisdell threads these biographical resonances throughout Creating Anna Karenina, presenting a view of Tolstoy’s life that makes the writing of Anna Karenina feel almost inevitable. As well as the crimes of passion that seem to abound in Tolstoy’s social circle, there is also the summer he spends on the Russian steppe witnessing firsthand the poor implementation of the government’s agrarian reforms. Such experiences, scholars agree, no doubt played a role in his fashioning of the character of Konstantin Levin, who functions in the novel as a kind of mirror of Tolstoy, a wealthy landowner who tries to settle his crisis of faith by laboring alongside peasants in the fields.

Despite these sources for inspiration seemingly all around him, Tolstoy still struggled to write throughout 1872. His breakthrough the following March came when by chance he started leafing through the collected works of Alexander Pushkin. Suddenly, for reasons unclear, Tolstoy was jolted into action and sketched the entire plot of Anna Karenina in short order. As he wrote to a friend at the time, “I thought up characters and events, began to go on with it, then of course changed it, and suddenly all the threads became so well and truly tied up that the result was a novel which I finished in draft form today, a very lively, impassioned and well-finished novel which I’m very pleased with and which will be ready in 2 weeks-time if God gives me strength.”

Two weeks turned into four years, as it happens. After submitting the first installment, which was published in The Russian Herald (the same journal that earlier published War and Peace and Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment), Tolstoy found himself distracted and disinterested. “My God,” he wrote to his friend, the literary critic Nikolai Strakhov, “if only someone would finish A. Karenina for me! It’s unbearably repulsive.” Tolstoy’s wife Sonia, who did his copying, had been ill from consecutive pregnancies and sick with grief after losing a daughter just hours after giving birth. Tolstoy also absorbed himself into his school for peasant children, further developing his alphabet primer, and often wondered if Anna Karenina was a useless indulgence in comparison with his work on education. The latter half of Blaisdell’s book is rife with letters to friends that show how plagued with self-doubt Tolstoy was at this time. “I’m disgusted with what I’ve written,” he tells Strakhov. “I need to cross it all out and throw it away and disown it and say ‘I’m sorry, I won’t do it again.’”

Such letters are perhaps the highlight of Creating Anna Karenina because they bring us closer to Tolstoy’s inner world and creative process in a book that otherwise feels overly terrestrial. For Blaisdell, the story of how Anna Karenina was made is firmly tied to what Tolstoy’s life looked like on a day-to-day basis—whose governess was seen with whom. This method has its limitations. Blaisdell tells us about the changes that occurred between drafts but offers little insight into why Tolstoy, who initially sketched Anna as contemptible, silly, and unattractive, transformed her into one of literature’s most charismatic and complex heroines.

To do so would require a much deeper engagement with the French novel of adultery, to which Anna Karenina was a direct response. Blaisdell only briefly alludes to the Alexander Dumas fils essay “Man-Woman” (1872), which claimed that men had the right to kill unfaithful wives (the essay ends with the words “Tue-la,” or “kill her”). Despite her grim fate, Tolstoy’s adulteress was treated with relative sympathy and complexity compared to her French antecedents. In ultimately refusing to make Anna a caricature of cruelty or Karenin a totally pure and pitiful soul, Tolstoy undid the conventions of the genre, preferring to explore the potential for anyone to be overtaken by desire.

To read Anna Karenina this way requires not seeing Tolstoy as simply a sui generis artist who stumbled around his estate collecting anecdotes. Like all writers, Tolstoy read voraciously and borrowed extensively; his art was a response to other art as much as it was to daily life. Perhaps Blaisdell has simply fallen for Tolstoy’s tricks, his feats of realism that make you forget you are reading a deeply plotted and contrived work of fiction. The short story writer Isaac Babel said of him: “If the world could write by itself, it would write like Tolstoy.” Or at least like he wrote when he finally got around to the task. The curative mare’s milk, it turns out, was slightly alcoholic; unable to get any writing done, Tolstoy wrote his daughter: “Laziness quite overpowers one when taking koumiss.”