Ronald Reagan began laying the groundwork for his 1980 presidential run almost immediately after his defeat in his campaign for the 1976 Republican nomination. The work consisted primarily of hundreds of speeches in hotel ballrooms across the country. The most important addressed high-minded fora like the Foreign Policy Association in New York and the Public Affairs Council in Washington, D.C., from texts carefully worked over by many hands in order to present the former governor as a dignified statesman in the broad center of respectable opinion.

The vast majority, however, were stops on what Reagan termed the “mashed potato circuit.” It was there that, for a $5,000 fee, Reagan presented the same sort of fantastical anti-big government parables he’d been offering up to gatherings of trade organizations, civic clubs, conservative groups, and (for a discount) Republican organizations since the early 1960s—with plenty of loony Cold War panic stirred in for good measure. For instance, the time in Palm Beach, Florida, in 1977, when he fantastically claimed that the Soviet Union had sent 20 million young people into the countryside to practice reconstructing their society in the event of nuclear war. The Soviets had supposedly also “dispersed their industry” in preparation for an ultimatum the Kremlin intended to issue to the United States “as early as next year and at least by 1981”: Surrender, or face Armageddon. According to Reagan, the Soviets believed “that if there was such a nuclear exchange, they could destroy us and we couldn’t destroy them.”

He sounded like Dr. Strangelove. Which presented quite the dilemma for the Reagan aides who wrote those statesmanlike speeches, like Peter Hannaford and Michael Deaver—who hoped to reassure establishment elites that, despite what you might have heard about Ronald Reagan being a dangerous extremist, he actually was one of them.

By 1978, any number of initiatives were underway to advance that crucial political goal. One went by the acronym PTWWT. That stood for “People to Whom We Talk”: a continually updated list distributed to reporters to reassure them of Reagan’s association with distinguished foreign policy personages like Henry Kissinger, NATO commander Alexander Haig, and Harry Rowen of the RAND Corporation.

A related effort was the “SP Program”: a formal process for staffers to draft letters to opinion leaders for the governor to “sign personally.”

You can find them filed away in the papers of Hannaford and Deaver at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. They frequently praised books and articles the recipient had written. On December 14, 1978, for example, an SP letter went out to The New York Times’s most liberal columnist Anthony Lewis, responding to his piece about famous Kennedy assassination conspiracy theorist Mark Lane. “It is probably safe to say that over the years, had we compared notes, we would have found ourselves in disagreement on many issues,” the letter ran. “But when your column ‘The Mark of Zorro’ caught up with me on my return from Europe the other day, I found myself in agreement with every paragraph. Perhaps we can become co-chairmen of the Ad Hoc Committee to Tune Out Mark Lane.… Thanks for saying what needed saying.… Sincerely, Ronald Reagan.”

The rightward-tending Democratic Party intellectuals of the 1960s and ’70s—the “neoconservatives”—were a special focus. For instance, an SP letter went out to “Norman and Midge”: Norman Podhoretz, editor of Commentary, and his wife Midge Decter, of Harper’s. It had Reagan claiming to have “finally caught up with the Sunday New York Times of June 11 and your article ‘The Cold War Again.’ I think you made an excellent point about the semantic differential in the U.S. and Soviet interpretations of agreements such as SALT I and SALT II.”

Another special focus was moderate Republican elected officials. “Dear Pete,” a letter ran to Delaware’s Governor du Pont. “I saw an item the other day about your signing into law a bill which allows Delaware motorcyclists to ride without helmets. I agree with your remark that anyone who does so is ‘damn foolish,’ but I agree wholeheartedly with your action. We went through the same thing in Sacramento, with the same conclusion—it just wasn’t any of government’s business.”

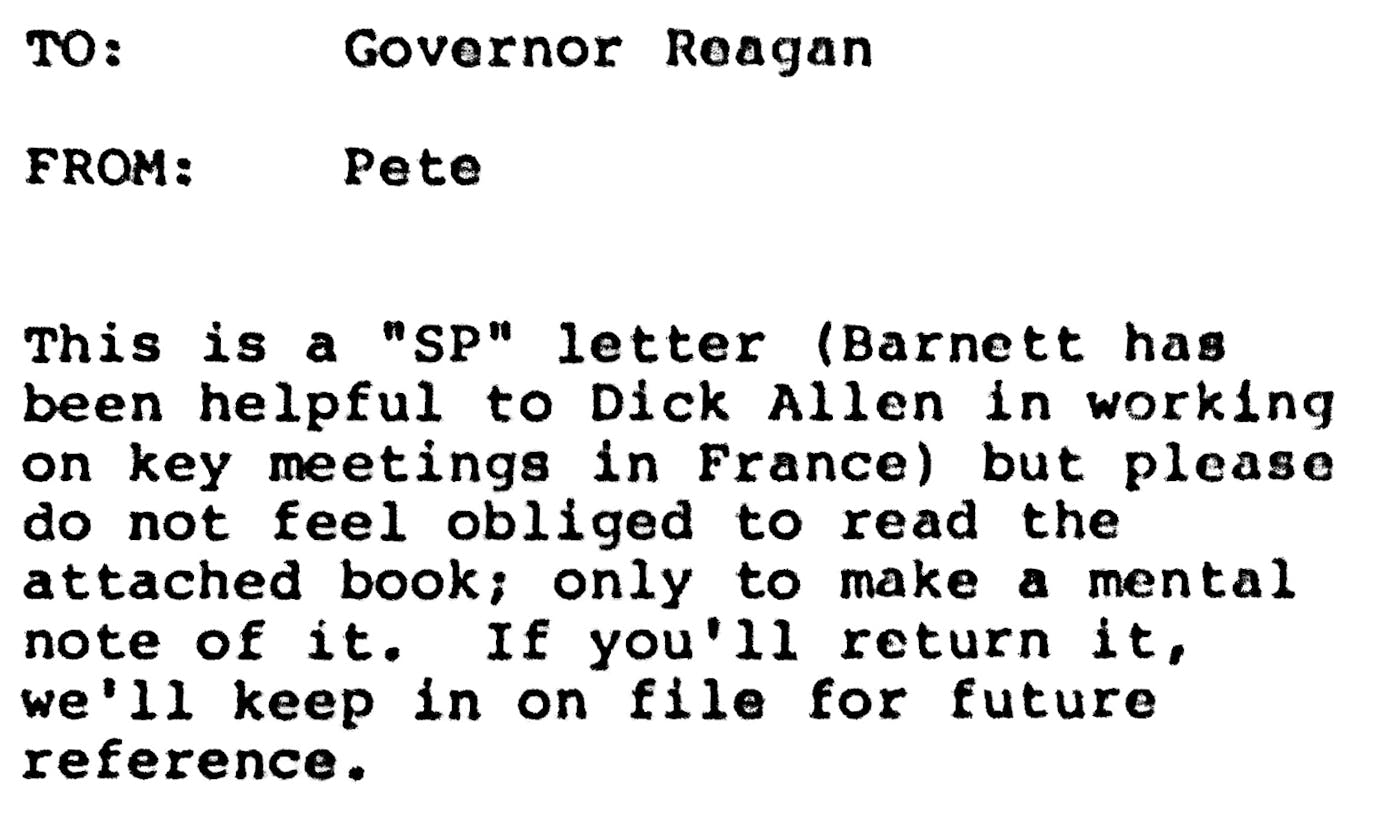

The more naïve among these

correspondents would have been mightily disillusioned if they saw the sausage

being made. One SP letter thanked a think tank intellectual for sending along an

“absorbing but sobering” book. It went to Reagan for his signature with a cover

note: “Please do not feel obligated to read the attached book.” Another was to

the Catholic intellectual Michael Novak, praising him in a way that suggested

Reagan had just newly encountered his work—even though the standard speech

Reagan was then delivering included a line about how liberalism these days was

a creed that only the rich could afford, quoting one Michael Novak. A

missive to Harper’s Washington editor Tom Bethel on his “interesting,

informative” piece, “The Liberal Carter” was forwarded for Reagan’s signature on

August 3, 1978—along with a thoughtful request, apparently to a secretary, to “send

article along to RR to read.”

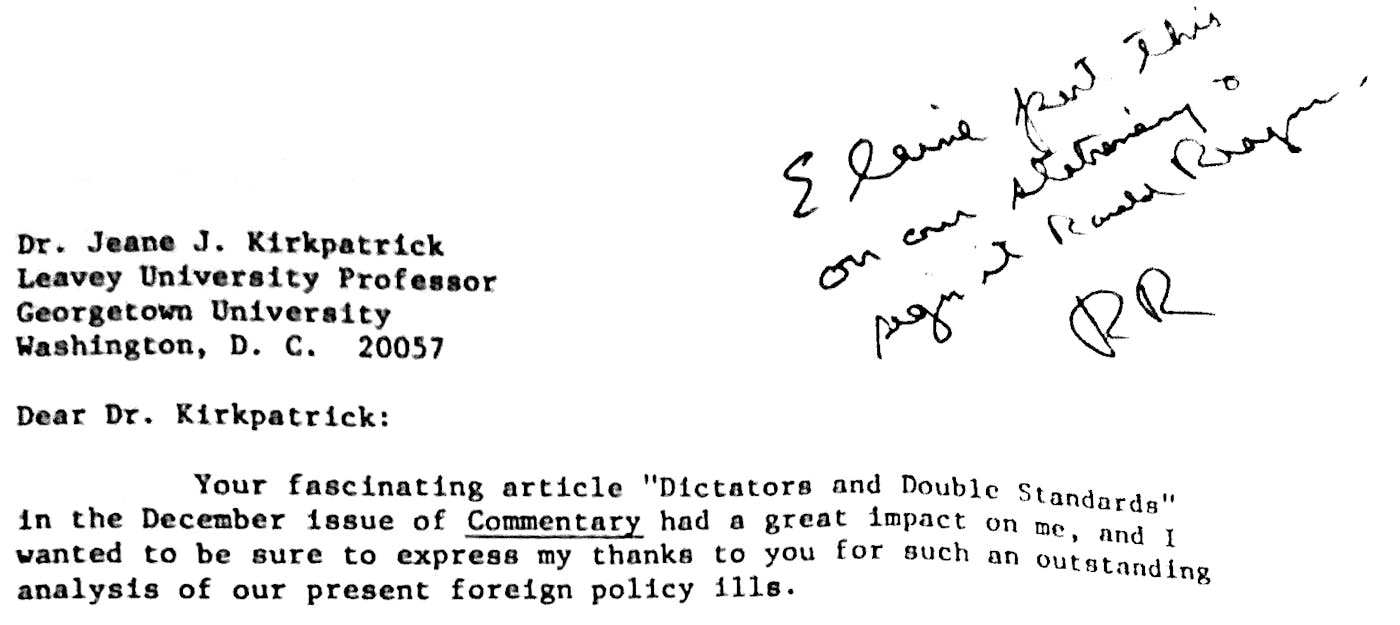

Another went to the author of an article in Commentary magazine: “Your approach is so different from ordinary analyses of policy matters that I found myself reexamining a number of the premises and views which have governed my thinking in recent years.” The article, by a neoconservative Georgetown professor named Jeane Kirkpatrick, was called “Dictatorships and Double Standards” and later became famous for outlining the Cold War rationale for supporting friendly authoritarian regimes in the name of countering the red menace—in other words, for maintaining a single standard against communism. The SP response was almost comical because the supposedly novel argument that had hit Reagan with the force of a ton of bricks was identical to one he had been repeating for years—for instance, telling an audience of 2,000 at the Waldorf Astoria in a speech quoted in The New York Times that human rights policy must follow “a single, not a double standard.”

Richard V. Allen—Reagan’s self-promoting chief foreign policy adviser, responsible for the letter Reagan signed—spun an elaborate tale that Kirkpatrick recounted for an oral historian: He claimed he had passed her article to Reagan before he boarded a plane from Washington to California. Reagan supposedly breathlessly called Allen during a stopover in Chicago:

“Who is he?”

“Who is who?”

‘Who is this Jeane Kirkpatrick?”

“Well, first, he’s a she.”

“Reagan wrote to Kirkpatrick in December”: That’s how one Reagan scholar, Steven F. Hayward, puts it, despite the fact that Reagan had not only probably not written it but didn’t even sign it personally. A note from Reagan on a draft read: “Elaine put this on stationary & sign it Ronald Reagan.”

Be that as it may: Flattery worked. Kirkpatrick, in an earlier Commentary article, had criticized the “strain of nativist populism” represented by the New Right, who had called for conservatives to expand their base by attracting what one called “millions of working- and middle-class Americans [who] feel betrayed by a system which they see as ever more alien” by using the most emotional and anti-intellectual appeals possible. Kirkpatrick and her neocon confreres overcame their embarrassment at their down-market coalition partners and made the leap to Reagan nonetheless; Kirkpatrick ended up his United Nations ambassador.

Recipients frequently responded to the SP letters in effusive, highly personal terms. So it was that several rounds of animated correspondence with “Nat”—neoconservative Harvard sociologist Nathan Glazer—followed an SP on the subject of subway graffiti and urban disorder as well as “the relative attractiveness of welfare to work.” It’s possible that Reagan was involved in composing his own side of the exchange, but it’s likely that he was not. It’s almost like a 1970s Turing test—one that every Reagan scholar I’ve read fails. Letters like the one to Kirkpatrick pulled from the “SP File” at Hoover are quoted as if crystalline portraits of the interior of Ronald Reagan’s mind.

Meanwhile, no one seems to ever have noticed—or if they have, they have bent over backward to repress—another entirely separate file of Reagan correspondence. This one is 350 miles south as the crow flies at the Ronald Reagan Library and Museum in Simi Valley, and it depicts a very different sort of fellow indeed. I refer to the letters Ronald Reagan dictated.

These missives go to a very different cast of characters, with not a single overlap with the Hoover cache of which I’m aware: a high proportion are to friends from his Hollywood days and Iowa and Illinois pals to whom he reminisced about past sports glories. They aren’t addressed to liberal New York Times columnists but far-right newspaper publisher William Loeb, just the sort of “nativist populist” against which Kirkpatrick set her sights in Commentary. (One of the signed front-page editorials in his Manchester Union Leader, the only statewide newspaper in New Hampshire, concluded, “When the Russian Communists lead hordes of black terrorists to slaughter whites in South Africa on a large scale, the American white population will have been so brainwashed that instead of reacting to support their fellow whites in South Africa they will sit by and do nothing.… RUSSIANS ARE PREPARING THE AMERICAN MIND TO ACCEPT THE RUSSIAN BLACK CONQUEST OF SOUTH AFRICA. IT IS AS SIMPLE AND DIRECT AS THAT.”) Or another Jeane, an old Reagan friend—newspaper psychic Jeane Dixon.

In one dictation, he muses how “the Old Testament prophesies that would foretell Armageddon” related to recent events in the Middle East. Another went to Dr. George S. Benson, a McCarthyite fundamentalist minister who in the 1950s had turned his tiny segregated Bible college in Searcy, Arkansas, into a factory for hysteric propaganda pamphlets and films about communist infiltration of the U.S.; Reagan concurs with his worry about liberal textbooks subverting young, impressionable minds. It was dictated, as it happened, the same day a Kissingerian telegram drafted by Richard Allen went out under his name, congratulating the newly elected prime minister of Japan and proposing a back-channel political alliance.

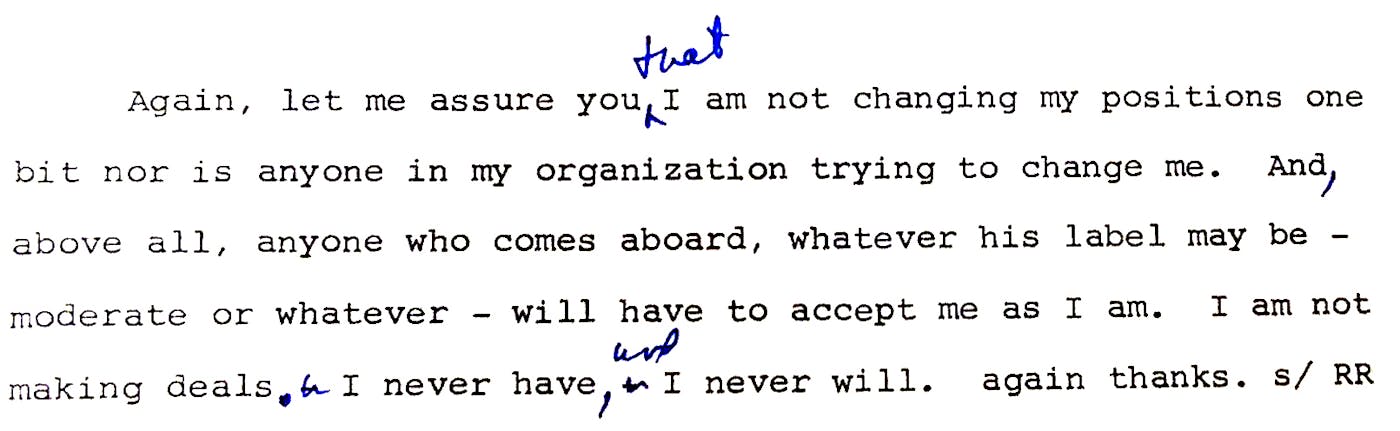

Many dictated letters also went to apparent strangers. These tended to concern the exact same subject: the notion—more and more abroad in the land thanks to his statesmanlike speeches to audiences like the Foreign Policy Association in New York and the Public Affairs Council in Washington, the assurances to media elites concerning “People to Whom We Talk” and all the carefully manufactured SP letters—that he was moderating his ideology. No accusation apparently vexed him more.

In a typical one, Reagan dictated defenses against a series of alleged apostasies. The correspondent had been baffled that he had come out against a 1978 initiative to bar gays from teaching in California schools; Reagan reassures him that “if it ever becomes necessary to have an additional law denying homosexuals the right to advocate their lifestyle, I’ll be the first in line to support it” and also that “I always have been unalterably opposed to gun control.” (This was not true: he signed a strict gun-control law in 1967 after armed Black Panthers visited the Capitol building in Sacramento.) Finally, he said that the only action he had ever taken concerning school integration in California was “a law giving authority over schools to the local school boards in an effort to keep the decisions from being made by judges in our courts.”

He reserved his most defensive language for those accusing him again and again of endorsing Senator Charles Percy of Illinois, a liberal Republican, in the closing days of the 1978 Congressional election. “I realize there were some who thought it was betraying the faith to do that,” he wrote to an old friend. To another, he detailed that he had only spoken for Percy at one single event because he had been veritably ambushed by political friends to do so. “This was the extent of my campaigning for Senator Percy,” Reagan huffed. “I’d be very interested, if you don’t mind, in finding out where you received this erroneous information.”

He had actually spoken for Percy at least four times. The lie was a small one but also quite telling. For, six weeks after that particular dication, he embarked on the most important trip of his 1980 efforts thus far to Washington D.C. His agenda was winning over the likes of Chuck Percy that he should be the party’s consensus pick for the nomination and convincing them that he was no kind of extremist at all. One of his stops was a luncheon hosted by Percy ally, Illinois Governor James Thompson, who had previously said that if Reagan were the nominee, “We wouldn’t recover politically for a generation.”

He was wrong—in part because once

he was in the White House, the same people did such a good job hiding the guy

who dictated those letters from the people who received the ones he merely

signed. It will take a guy whose lunacy it is impossible to hide to

accomplish that trick 40 years later, God be willing.