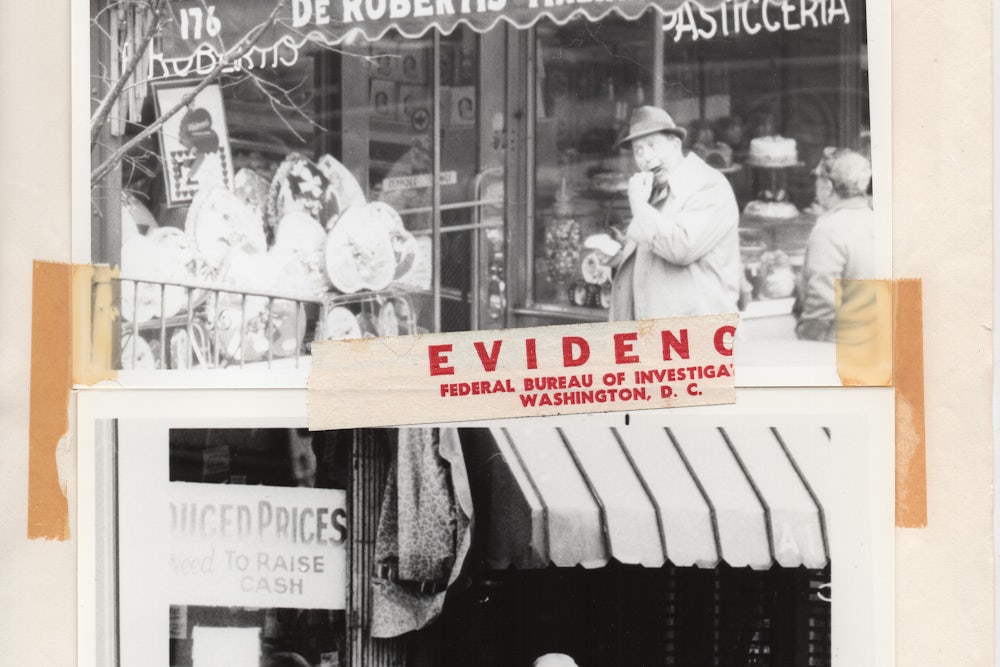

It’s 1980, and Joe Cantamessa is dressed as a television repairman. He’s actually with the Federal Bureau of Investigation: Paul Castellano, head of the Gambino mob family and the New York City Mafia’s “Boss of Bosses,” loves TV. A whiz at barely legal covert operations, Cantamessa messed with the target’s wiring until Castellano called the TV company to complain. Now Cantamessa stands in his borrowed boilersuit, hemming and hawing over a set that is malfunctioning because his colleagues outside are causing it to. He gets a mob underling to hold the flashlight while he installs the fateful bug.

We hear all this from a white-haired Cantamessa, recalling his youth while seated inside a dark sedan parked, for some reason, under a New York City bridge. Such are the creative flourishes added by director Sam Hobkinson to his three-part documentary, Fear City: New York vs. the Mafia, now available to stream on Netflix.

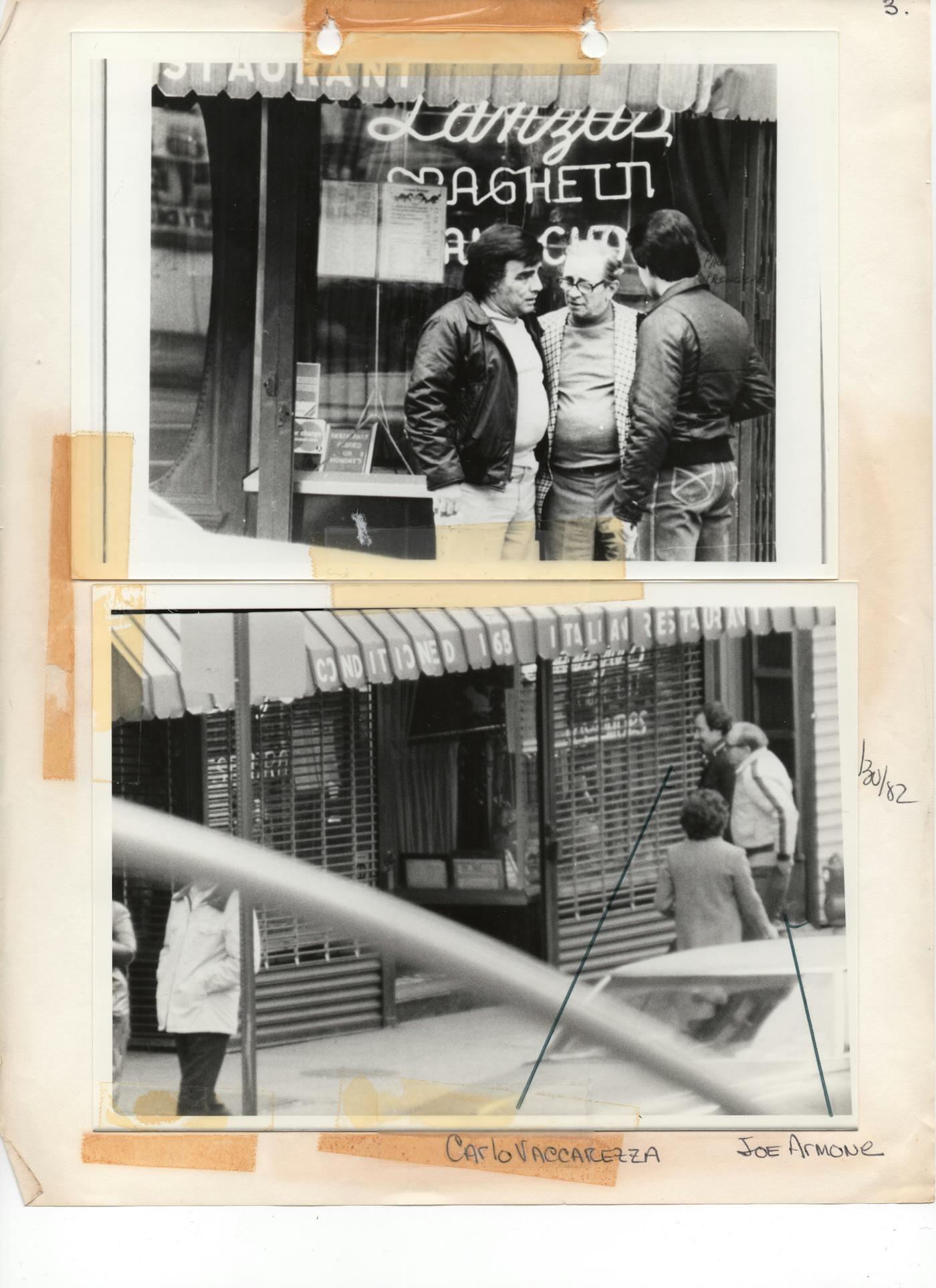

Hobkinson’s documentary focuses on the families Gambino, Lucchese, Genovese, Bonanno, and Colombo, who ran a shadow government across New York from the 1930s to the 1980s. Cutting archival footage with the FBI’s own surveillance tapes, photographs, and agents (retired now, but all with intense, flashing eyes), he first lays out the scene in 1979.

The mob controlled New York’s restaurants, gasoline, construction, trucking, trash management, retail—everything. From the trucking teamsters to the fish business, they puppeteered the labor unions, calling in strikes to get their way and throwing the odd construction worker out of a window if they didn’t. As New York’s skyscrapers flew up over the 1970s, so did the mob’s profits. The Mafia essentially skimmed 2 percent off the top of the entire city, the talking heads explain, for decades.

The best testimony comes from former mobsters themselves: Compared to cops, they’re entertaining to watch. Johnny Alite, a former heavy for John Gotti who turned state’s witness, and Michael Franzese, a Colombo family loan shark who did 10 years inside, both describe their old jobs for the camera. Franzese would lend out cash at obscene rates of interest, then forcibly “partner” with his clients with whatever business they had to give him. He got a Chevrolet dealership that way—which just goes to show that, whether legal or illegal, predatory lending tends to have the same outcome.

Law enforcement gets the most lines, however. Hobkinson introduces the ragtag gang of enforcers who sliced the heads off the city’s Mafia hydra. From the cops on the street (e.g., Roy Lindley DeVecchio or Joe Cantamessa) to the lawyers (e.g., John Savarese) who would help drag the Mafia into court, they’re almost all Italian-American themselves.

The most famous of these is, of course, Rudolph Giuliani. The future mayor of New York City was born in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, where his own father worked as an enforcer for a gambling and loan-sharking enterprise at a nearby restaurant. We hear his memories of growing up tough, of the Mafia shaking down mom and pop store owners, forcing them to pay exorbitantly for their trash collection, and so on.

Little Rudolph Giuliani grew up to be the United States associate attorney general from 1981 to 1983, then U.S. attorney for the southern district of New York from 1983 to 1989. As a U.S. attorney, he led the so-called “Mafia Commission Trial,” which used the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, to gather together 11 major gangsters (including bosses from all Five Families) in a single case.

RICO is an unusual law, in that it allows for the prosecution of an enterprise rather than a single person. As its author, professor G. Robert Blakey, explains in Fear City, it was a lecture on the law he gave to the FBI in the late ’70s that revolutionized its approach to crime. Instead of trying to go after individual soldiers, laboriously grinding up the chain of command, it would now simply have to prove that there was an executive board at the top of the Mafia, called The Commission, and that it was the underlying authority behind the city’s violence and corruption.

Giuliani succeeded in sending three heads of the Five Families to jail, but he also caused several of them to be murdered by their own colleagues—including Paul Castellano himself.

The tapes—fruits of the bugs Cantamessa installed—are so lurid that they’re difficult to distinguish from Hollywood fiction. Right at the show’s start, for example, we hear a man named Chuck get a serious warning “Chuck, I’m gonna tell you something. You have that fucking 200 in my hands tomorrow. If you ain’t got the 200 in my hands tomorrow, I’ll break every fucking bone in your body, I swear to my kids, you understand?”

The voice is nasal, its mannered tone so recognizable from The Godfather (or Goodfellas, Casino, Once Upon a Time in America) that it is difficult to remember that this is a documentary.

Decades of sensitive, sophisticated filmmaking about the Mafia means that the average viewer sees a mobster as a human being, not a cartoon murderer.

This is where Fear City falls down. Without providing much in-depth analysis of the mob’s effect on society—horrifying in many cases, to be sure—Hobkinson expects his viewer automatically to be on the FBI’s side. Despite the documentary’s juicy tapes and cinematic subject matter, Hobkinson seems to forget what year we’re living in. If there’s any key theme to 2020’s cultural politics, it’s that American law enforcement, not to mention Rudy Giuliani himself, has completely lost its right to our automatic sympathies. Reagan’s head flashes up in one bit of archival footage, saying that the American family is the key to creating wealth. Isn’t that exactly what the Italian Mafia in New York did—turn family ties into a whole system of social governance?

Mobsters kill people. But so do the police. Fear City takes it for granted that you will sympathize with FBI agent Marilyn Luchts when she calls a relationship between Castellano and a maid named Gloria “sordid” and laughs about the colleague who had to listen to them having sex. That tape came from a bug planted by the police inside a private residence. Castellano was a criminal, sure, but Gloria? She was a regular working-class human being, one in a vulnerable position with her employer, and her treatment at the hands of the FBI (Cantamessa personally lied to her while undercover, extracting her secrets) is downright offensive.

Worst of all, Fear City uses one single bit of archival footage featuring Donald Trump, the most famous landlord in New York City, and one bit of surveillance tape mentioning his name—out of context, meaning you can’t understand it. As Wayne Barrett mentions in his 2016 biography of Trump, however, the businessman’s interests in casinos and real estate means that he constantly did business with the Mafia. The show conspicuously tiptoes around that business, although the information is out there. Beyond the contextual information that all construction in the early 1980s was controlled by the mob, therefore implying that all landlords collaborated with them, Fear City avoids any discussion of the sitting president of the United States of America and his role in the networks the show’s protagonists sought to prosecute.

It’s possible that Giuliani, Trump’s most bizarre and frothing stooge, refused to appear alongside criticism of the president. Whatever the case, that faux political neutrality renders Fear City a celebration of law enforcement and a portrait of Rudy Giuliani’s own mythology—the tough guy who cleaned up New York—rather than a documentary.

In real life, there’s no magical binary dividing the wicked from the virtuous, the thugs from the knights. If a director wants to pretend that there is, he must work to earn his audience’s trust, the same way that the police must earn the citizens’ trust if their work is to have any positive effect. Fear City declines to do that work and therefore fades into the long and indecorous canon of subpar entertainment about bad guys. File it next to City Heat under “Mob films, Dime-store.”