To think about Hillary Clinton is to enter a maze of counterfactuals. The smaller what-ifs and the bigger, more fundamental ones chain together in infinite combinations. There is the flurry of 2016 election questions: What if she had seen off competition from Bernie Sanders earlier in the Democratic primary? What if she’d been spared more investigation into her emails in October? What if she had campaigned harder in Michigan and Wisconsin? Then there are more personal, existential questions: What if she’d run for office earlier in life, putting her own ambitions ahead of Bill’s? What if she’d declined to stand by him through the scandals of his career? What if they’d never met?

More than any other politician of recent years, Hillary Clinton has served as a way of glimpsing what might have been. Screenwriters have been imagining varieties of Hillary for over a decade—in Veep’s Selina Meyer, CBS’s Madam Secretary, House of Cards’s Claire Underwood—while two much-discussed, unproduced screenplays romanticize her early life and potential. The Hillary Clinton extended universe has something for all ages: For children, there is A Girl Named Hillary, as well as Chelsea Clinton’s She Persisted franchise; for teens, there is Hillary and Chelsea’s co-authored Book of Gutsy Women. There’s her memoir on the ordeal of 2016, What Happened, and the four-part Hulu documentary series on the same events, which radiates disdain not only for Donald Trump but also for Sanders’s challenge from the left. Rarely have roads not taken been so obsessively explored.

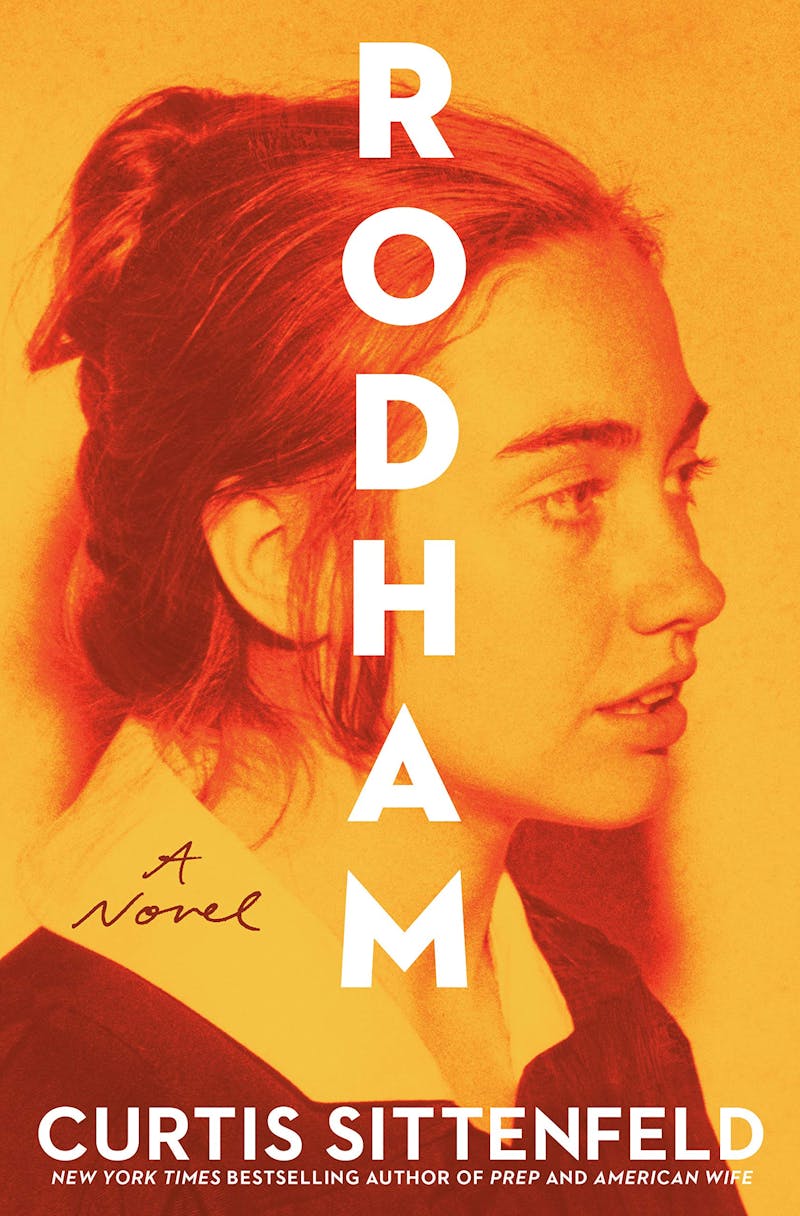

This is the terrain on which Curtis Sittenfeld’s novel Rodham plays out, the story of an exceptional young woman whose brilliance and verve for leadership are recognized early in life—from her rousing commencement speech at Wellesley, celebrated at the time in LIFE magazine, to her triumphs at Yale Law School—and who wins the prize of the presidency in 2016. As the title suggests, that victory is not the only counterfactual woven into the book. This is an alternate universe, in which Hillary doesn’t marry Bill to become Hillary Rodham Clinton but remains Hillary Rodham, retaining a certain integrity as she’s liberated from this man’s ambitions and catastrophes, and from the many compromises of a life with him. The version of Hillary we get here is a kind of politics nun. “In the White House, on a typical weeknight,” she recalls, “I make my nest in the Living Room,” surrounded by books and papers, sustained by cups of tea and her commitment to public service.

That soothing image makes a stark contrast with the reality of Donald Trump’s evening binges on Fox News. But the way the novel arrives at a Hillary presidency is an unexpectedly tangled one. It is not the story of a woman shorn of a problematic man and finally able to shine. Rather than a fantasy of Hillary’s potential fulfilled, it reimagines major parts of her character, removing from her any of the major flaws or contradictions that could hamper a politician in the MeToo era. Perhaps the strangest aspect of Rodham is that in crafting an exemplary version of Hillary Clinton, the book—apparently unwittingly—presents a harsh critique of the person we know today.

Before the novel gets to its fork in history, there is a lot of self-consciously steamy sex. The first chunk of the book hews closely to the true story of Hillary and Bill meeting at Yale Law School in the 1970s, dating, and moving to Arkansas, where Bill long planned to begin his political career. Much of the well-known biography of both figures features heavily here, upcycled into a painful kind of exposition. Hillary recounts passages of her actual commencement speech; Bill introduces himself, in case we didn’t know, as the man from Hope. The pair grows closer as he shares the familiar origin story. “When my mother was pregnant with me, my father was killed in a car accident”; then came his stepfather, “a mean old drunk.”

The vivid descriptions of sex seem to be Sittenfeld’s way of differentiating her fiction from the biographies and memoirs she cites as source material in her acknowledgments. Come-ons as self-satisfied as “you’re the smartest person at Yale” lead to raptures of intellectual and sexual recognition. (“I really enjoy discussing theology with you,” he says. “And then he plunged inside me,” she recalls.) When house-sitting for a friend, they have sex in the hot tub every night: “It’s like we’re ingredients in a soup,” Bill tells her. For all the cringe-inducing detail, the point here is to capture how much Hillary is sacrificing when she separates from Bill. She’s spent her early life at a remove from her peers, caught in the “loneliness of being good at something”; now here is a person who both desires and respects her, someone with whom she can envision a future. “Strategizing made me feel as close to him as sex,” she reflects, at the high point of their relationship.

As in life, we see the relationship tested when Bill is casually, compulsively unfaithful, and when Hillary realizes that living in Fayetteville, Arkansas, won’t afford her the same professional opportunities she’d have in Boston or Chicago. But the turning point comes during Bill’s 1974 run for Congress. As Hillary Rodham is walking through a grocery store parking lot, she finds a woman waiting for her at her car. The woman explains that she was a volunteer on the campaign, and that Bill Clinton sexually assaulted her. The incident she describes bears a striking similarity to Juanita Broaddrick’s allegation that Bill Clinton assaulted her when she was working on his 1978 gubernatorial campaign. It’s the first of several similar reports in the novel, each of which resembles those of Clinton’s real-life accusers (none of whom are mentioned by name).

When Hillary eventually confronts Bill about the encounter in the parking lot, it becomes one of five reasons she can think of for breaking up with him. The way she conceptualizes the alleged crime, however, leaves no room for ambiguity: “Already, he’d been accused of assault.” And as time goes by, her narrative about the end of the relationship hardens into one in which the assault was the breaking point. Later, she’ll hesitate to vouch for him when campaign reporters call her. (“How can I when you could be publicly accused of rape at any time?”) She’s clear on the reason he should never become president: “He’s a sexual predator.”

This is the novel’s third big counterfactual: What if Hillary Clinton had chosen to believe a victim of sexual assault over loyalty to the man she loved? The fictional Hillary’s clarity on the question allows Sittenfeld to imagine the glories of her political ascendancy, but it doesn’t connect back to the actually existing Hillary Clinton very smoothly. The most charitable reading of the parking lot encounter is that it gives the fictional Hillary the chance to see the worst side of Bill before she enmeshes her life more tightly with his. It’s notable that this incident takes place in 1974, four years before the one Broaddrick has described; by 1978, the Clintons had already been married three years, and Broaddrick’s story would not become public for another 20 years. Nonetheless, the moral certainty of the fictional Hillary Rodham makes an awkward contrast with real Hillary Clinton’s position on similar stories, which remains at best unclear.

That dissonance is hard to ignore through the rest of the novel. Her break from Bill is the choice that enables her to become an accomplished and well-connected law professor at Northwestern, politically one to watch in her thirties, and a United States senator by her forties. Her main regrets center on loneliness and the problems of dating while becoming ever busier and more prominent. It’s also a turning point for Bill: Without someone of Hillary’s acumen and intelligence by his side, his 1992 presidential bid falls apart when he’s grilled on 60 Minutes about his affair with “a cabaret singer in Little Rock” (again, not named). It’s a moment of vindication for the Hillary Rodham character in the novel, as is her later discovery that Bill has settled a sexual harassment lawsuit for $850,000. Her distance from him is her most consistently reinforced moral position.

Perhaps a bigger problem for the book as a work of fiction is its trouble imagining just how Hillary Rodham would have turned out absent the privileges and the traumas of her time as first lady and her decades at the very top level of American politics and global power. This character has none of the determined pragmatism, none of the insistence on courage in the face of intractable problems, of the Hillary Clinton who titled her 2014 memoir Hard Choices. It would be hard to see her running on experience the way her real-life counterpart did in 2016: She shows little interest in national security, and one can imagine the press criticizing her for lack of a coherent foreign policy. This Hillary is not asking who you want answering the phone at 3 a.m. and doesn’t seem to be the candidate who “already knows the world’s leaders, knows the military.” (Henry Kissinger, described by the real Hillary as a “friend,” is a guest at a political soirée later in the novel, but, like ships that pass in the night, he and Hillary Rodham do not appear to know each other.)

What remains of Hillary Clinton in this character is a familiar awkwardness on the campaign trail. There is an embarrassing incident in which Hillary Rodham attempts to go viral, releasing a video of herself asking, “Does this hat make me look on fleek?” There is her single-minded cultivation of a cancer patient named Misty LaPointe, whom she meets at a rally and magnanimously connects with “her team”; after a few friendly texts, it transpires that her motive is to get Misty, an Iowan, to announce her to the crowds at a crucial campaign stop. Throughout the book, she talks like a politician; the novel has the taut cadences of a stringently focus-grouped narrative. Her sentences are even-handed to a fault and tinged with insincerity, even when she’s discussing sports with family. “This season does seem promising, but I’m trying not to get my hopes up,” she texts her brothers.

Then, because I’d learned from giving speeches that ending with the negative half of a mixed sentiment made the whole thing seem pessimistic, I deleted what I’d written and typed instead, I’m trying not to get my hopes up, but this season does seem promising.

What makes this version of Hillary run? Without a guiding philosophy, Senator Rodham turns out to be a surreal composite of women in politics. In the middle stretches of the book, she sounds a lot like Elizabeth Warren, a policy aficionado, law professor, and intellectual whose pitch to voters is that she will do a good job. But then she leans hard into packaging herself as a no-nonsense mid-Westerner with a big heart, Illinois’s answer to Amy Klobuchar. Also reminiscent of Klobuchar (and the basis for a scene in Veep) is Senator Rodham’s most distinctive scandal, as she’s attacked for making an aide shave her legs. Klobuchar and Warren’s memoirs are cited in the novel’s acknowledgments, along with books by Kamala Harris and Kirsten Gillibrand. It’s hard to know what to make of this amalgam, which seems to assume these politicians are more or less interchangeable and doesn’t really engage in what shapes a person’s agenda, their commitments, the trajectory of their career. They’re all women.

The book’s greatest departure from the present is its least thought-out twist. Having missed his chance in 1992, Bill Clinton comes back to challenge Hillary in the Democratic primary for the 2016 election. It’s Bill—who’s now made billions of dollars in tech and has been indulging in a Silicon Valley lifestyle of sex parties and veganism along the way—who becomes her antagonist, rather than Donald Trump, who decides not to run. It’s at Bill’s rallies that crowds excoriate Hillary, chanting, “Shut her up! Shut her up!” And it is Bill who pauses to let the chanting take its full effect. There’s a lot here that doesn’t make sense, especially when you consider that Bill is, in this scenario, still running as a Democrat, speaking to Democratic primary voters—a very different crowd than those at Trump’s rallies—and that his policies, Hillary acknowledges, closely resemble her own.

The purpose of this swerve in the plot seems to be to underscore that any version of Hillary running in 2016 would have attracted unheard-of levels of vitriol, whatever her record, whoever her opponent. Any possibility of her defeat is chalked up to a potent but formless and context-free sexism, which allows Sittenfeld to ignore any number of other factors that contribute to or detract from political success. The other purpose of the Bill-Trump switch seems to be to serve up a unique form of revenge on Donald Trump, stripping him of any ability to do serious harm to her and reducing his role in the story to that of a comical side character.

Trump is not the only significant figure from 2016 to be erased in Rodham. When Hillary steps up to the Democratic debate stage to contend with him, she also faces Martin O’Malley and Jim Webb—the person who is missing is Bernie Sanders. Perhaps the book’s most concentrated form of revenge is served on the senator from Vermont, who, in the real world, presented the most compelling critiques of Hillary’s politics, pushing her leftward on the issue of a $15 minimum wage and putting forward visions for free college and Medicare for All that have outlived his primary bid.

Sanders’s absence reveals a larger weakness of Rodham, which is its curiously limited view of what is at stake in American politics today. Not only is there no rising democratic social movement on the margins of this novel, it’s as if the 2008 crisis and Great Recession never happened. The 2016 election in Rodham turns out to be a contest between a sleazy Bill with his neoliberal platform and a respectable Hillary with a similar offering. The tensions unleashed and amplified by Trump’s run are missing here. So is the split within the Democratic Party and the broader generational divide between struggling young people and a set of more financially secure older voters. Granted, this is an alternate history. But surely the butterfly effect of Hillary and Bill’s breakup didn’t prevent the widening of these major rifts in society?

Rodham’s escapism takes a perversely narrow form. There’s no great political battlefield here on which Sittenfeld’s Hillary can fight to get to the presidency. With no substantial opposition from left or right, with no actual issues at stake, the arena turns out to be very small, and she never really gets to show what she’s made of. If the Hillary fantasy genre promises endless possibility, Rodham sets its sights a little lower, rewriting history only to make tweaks in the desired outcome. Nowhere is this clearer than in President Rodham’s pick for vice president: “I ended up going with the Virginia governor, Terry McAuliffe,” she explains. Sittenfeld has created a whole alternate universe in order to replace the most forgettable running mate in history with one of the most servile members of Clintonland. It’s not much to get fired up about. As Hillary gently jokes, “Terry is a decade younger than I am—we are just pale and stale.”

There’s no engagement here with the problem of where everything went wrong four years ago. The book is more interested in exploring Hillary’s sex life and her long-standing rivalry with one person—Bill—than in understanding her as a political actor with designs on a whole country. We learn more about old flames than ideology or strategy. Some of those intimate moments are handled with an unexpected subtlety, capturing the ways that competence and responsibility can leave powerful women isolated. It’s ultimately a lonely story. To imagine a different future for the country requires more than imagining a single person’s life had gone differently.