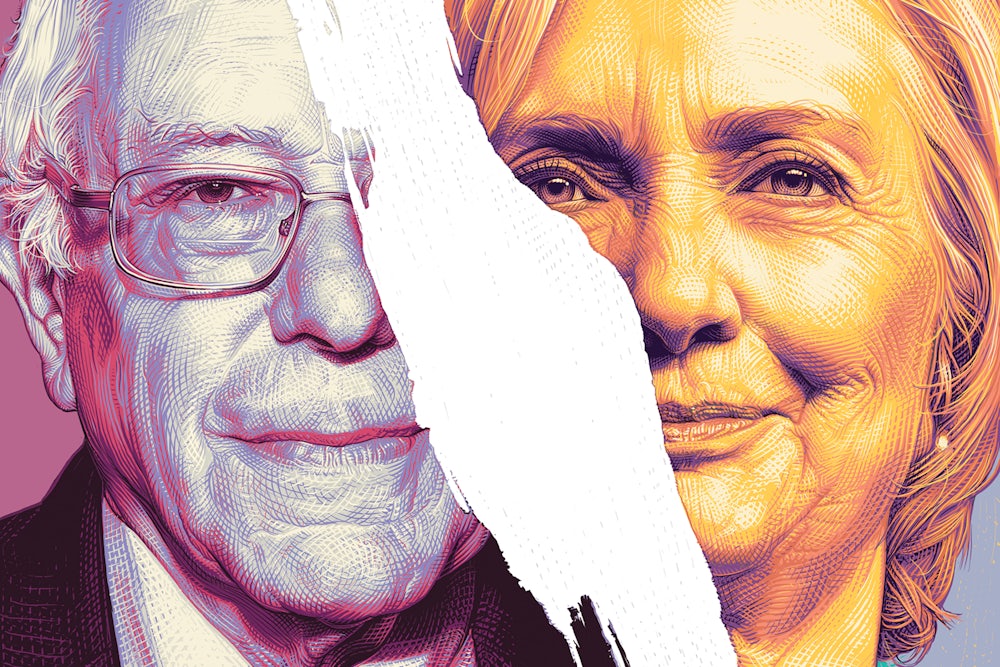

Throughout most of the 2016 presidential primaries, the media focused on the noisy and reactionary rift among Republicans. Until the battle between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders turned acrimonious in the home stretch, far less attention was paid to the equally momentous divisions within the Democratic Party. The Clinton-Sanders race wasn’t just about two candidates; instead, it underscored a series of deep and growing fissures among Democrats, along a wide range of complex fault lines—from age and race to gender and ideology. And these disagreements won’t fade with a gracious bow-out from Sanders, or a victory in November over Donald Trump. For all the talk of the Democrats’ need for “unity,” it would be a serious mistake to paper over the differences that came to the fore in this year’s primaries. More than ten million Democrats turned out in force this year to reject the party establishment’s cautious centrism and cozy relationship with Wall Street. Unless Democrats heed that message, they will miss a historic opportunity to forge a broad-based and lasting liberal majority.

To help make sense of what’s causing the split, and where it’s headed, we turned to 23 leading historians, political scientists, pollsters, artists, and activists. Taken together, their insights reinforce the need for a truly inclusive and vigorous debate over the party’s future. “There can be no settlement of a great cause without discussion,” observed William Jennings Bryan, the original Democratic populist insurgent. “And people will not discuss a cause until their attention is drawn to it.”

It goes way, way back

By Rick Perlstein

The schism between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders is knit into the DNA of the modern Democratic Party, in two interrelated ways. The first is ideological: the battle of left versus right.

Start in 1924, when the party cleaved nearly in two. That year, at Madison Square Garden, the Democratic convention took a record 103 ballots and 16 days to resolve a fight between the party’s urban wing and its conservative opponents. How conservative? Well, the convention was nicknamed the “Klanbake,” because one of the great issues at stake was—no kidding—whether the KKK was a good or a bad thing. The divide was so heated that tens of thousands of hooded Klansmen held a rally and burned crosses to try to bully the party into meeting their demands.

Eight years later, under Franklin Roosevelt, the party’s urban, modernist wing established what would become a long hegemony over its reactionary, Southern one. But that hegemony remained sharply contested from the very beginning. In 1937, bipartisan opponents of FDR banded together to forge the “Conservative Manifesto.” Co-authored by a Southern Democrat, the manifesto called for lowering taxes on the wealthy, slashing government spending, and championing private enterprise. Hillary Clinton’s eagerness to please Wall Street can be traced, in part, to that ideological split during the New Deal.

Indeed, over the years, many of the most “liberal” Democrats have remained sharply conservative on economic questions. Eugene McCarthy, the “peacenik” candidate of 1968, ended up backing Ronald Reagan. Dan Rostenkowski, the lunch-pail chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, proposed a tax package in 1981 that was more corporate-friendly than Reagan’s. Jerry Brown of California, long derided as “Governor Moonbeam,” campaigned for president in 1992 on a regressive flat tax. That same year, Bill and Hillary Clinton won the White House with the business-funded support of the Democratic Leadership Council, which sought to downplay the “big government” solutions championed by FDR.

Which brings us to the second strand in the party’s divided DNA: It’s sociological.

Slate’s Jamelle Bouie has pointed out the pattern’s clocklike consistency: Since the beginning of the modern primary process in 1972, the Democratic divide has settled into a battle between an “insurgent” and the “establishment.” But Bouie errs, I think, in labeling every insurgent as “liberal.” Just look at Brown in 1992—an insurgent who was conservative on economic issues. Or Hubert Humphrey in 1968 and 1972—an establishment favorite whose signature legislative initiatives, including centralized planning boards to dictate industrial production, were more socialist than those of Sanders.

This year, however, the traditional order of battle aligns with crystalline precision. Clinton, endorsed by 205 out of 232 Democratic members of Congress, is clearly the establishment’s pick—and also, increasingly, that of Wall Street masters of the universe terrified by the prospect of Donald Trump. Sanders represents the guerrilla faction, arrayed this time behind the economically populist banner of FDR.

Does history tell us anything about how Democrats can bridge their long-running divide and forge a stronger, more unified party? Sanders would do well to remember that sore loserdom never helps. (“George McGovern is going to lose,” a leading Democrat supposedly vowed after Humphrey lost the nomination in 1972, “because we’re going to make him lose.”) And Clinton needs to recognize that campaigning on economic liberalism is almost always a good political bet. (Even at the height of Reagan’s morning-in-America blather in 1984, barely a third of American voters favored his plans to reduce the deficit by slashing social programs.)

If Hillary has any doubts about embracing the economic agenda laid out by Sanders, she should ask the insurgent of 1992: William Jefferson Clinton. The man who ended a dozen years of presidential exile for the Democrats didn’t do it simply by promising to get tough on crime and to “end welfare as we know it.” He also pledged $80 billion in federal investments to improve America’s cities and to create four million new jobs—not to mention, of course, a plan to deliver health care to all Americans.

Rick perlstein is a historian and the author of Nixonland and The Invisible Bridge.

It’s Obama’s fault for raising our hopes

Jacob Hacker, professor of political science at Yale and co-author of Winner-Take-All Politics: We’ve now had almost eight years of a Democratic presidency. And with the exception of the policy breakthroughs in 2009 and 2010, they’ve been viewed as relatively lean years by many in the Democratic Party. There’s a sense of, “We went with someone within the system, and look what happened—Republicans still tried to crush that person. So let’s go for the whole thing.” There’s a sense that supporting the Democratic establishment and going the conventional route hasn’t been that productive.

Mychal Denzel Smith, author of Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching: A lot of young people who showed up to vote for Obama were voting for the very first time. But now they’re looking at the ways economic inequality persists, and they’re saying, “Oh, the Democratic Party doesn’t actually stand against that.” They’re looking at the deaths of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, the two big linchpins in the Black Lives Matter movement, and they’re like, “Oh, Democrats are actually the architects of the policies that have affected and continue to define young black life in terms of systemic, institutionalized racism.” So you have young folks getting into the Democratic Party and realizing they don’t have a place.

Astra Taylor, author of The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age: This is in part a symptom of the expectations that people had for the Obama administration that weren’t met. It got its first major expression through Occupy Wall Street, and it’s still playing out. Because nothing has changed, and people know that.

Ruy Teixeira, co-author of The Emerging Democratic Majority: You can make the case that Obama has been a very successful and progressive president, but people are impatient. What used to keep people in line, so to speak, when they had these kinds of dissatisfactions was, “Oh, I’m really frustrated, but what can we do? The country is so right-wing. We’ve got to worry about the national debt—there’s no room in the system for change.” Now there’s much more of a sense of possibility. The Democratic Party has contributed to this transformation by becoming more liberal, and by ceasing to be obsessed with the national debt and the deficit.

Elaine Kamarck, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of Primary Politics: Here’s the irony—the Bernie people are the Obama people. They’re all the young people; that’s the Obama coalition. They’re frustrated because under Obama, nothing much happened that they liked. They’re taking it out on Hillary, which is unfortunate, since she’s much more capable of making something happen.

Jedediah Purdy, Professor of Law at Duke and author of After Nature: The disappointment in Obama took a while to set in. The Obama campaign had the form and rhetoric of transformative politics, but not the substance. Many of us believed or hoped the substance might follow the form; but it didn’t. It turns out you need a program that challenges existing power and aims to reshape it. So Sanders represents the continuation of these insurgent energies. Clinton is also the continuation of Obama, but the Obama of governance, not of the campaign.

It’s Hillary’s fault for lowering our hopes

John Judis, former senior editor at The New Republic and co-author of The Emerging Democratic Majority: In 1984, you had Walter Mondale, a candidate of the Democratic establishment, pitted against a young upstart, Gary Hart. The split wasn’t left-right—it was young-old, energetic-tired, vision-pragmatism. Bernie, for all his 74 years, represents something still of the rebellious Sixties that appeals to young voters, while Hillary represents a tired incrementalism—utterly uninspiring and rooted largely in identity politics and special interest groups, rather than in any vision for the future.

The party hasn’t kept up with its base

Jill Filipovic, lawyer and political columnist: The party itself has been stuck in some old ideas for a while. You’ve been seeing movement around the edges, whether from Elizabeth Warren or these grassroots movements for income inequality. The pro-choice movement, for example, is a key part of the Democratic base that has liberalized and modernized and completely changed its messaging in a way that the party is now just catching up to. So you get these internal discords that dredge up a lot of bad feelings.

Danielle Allen, Director of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard: In the last 20 years, we’ve collectively experienced various forms of social acceleration. Rates of change in social dynamics have increased across the spectrum, from income inequality to mass incarceration to immigration to the effects of globalization and the restructuring of the economy. When you have an acceleration of social transformation, there’s a lag problem. The reigning policy paradigms will be out of sync with the actual needs on the ground. That’s what we’re experiencing now.

Jedediah Purdy: The people who have been drawn to the Sanders campaign have no love for or confidence in elites, Hillary’s habitus. And why should they? They’ve seen growing inequality and insecurity, the naked corruption of politics by oligarchic money, total cynicism in the political class of consultants and pundits, and wars so stupid and destructive that Trump can say as much and win the GOP primaries. There’s a whole world that people are surging to reject.

Bernie’s supporters aren’t living in reality

David Simon, creator of The Wire: I got no regard for purism. What makes Bernie so admirable is he genuinely believes everything that comes out of his mouth. It’s incredibly refreshing. If he didn’t have to govern with people who don’t believe what he’s saying, what a fine world it would be.

I look at the hyperbole from Bernie supporters that lands on my doorstep. Either it’s stuff they believe—in which case they’re drinking the Kool-Aid, so they’re not even speaking in the vernacular of reality. Or what they’re doing is venal and destructive. That level of hyperbole, which Bernie himself is not responsible for, is disappointing. The truth is, it’s not just your friends who have utility in politics—sometimes it’s the people who are against you on every other issue. If you can’t play that game, then what did you go into politics for?

Theda Skocpol, Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard: A lot of Bernie supporters are upper-middle-class people. I’m surrounded by them in Cambridge. I’m not saying they’re hypocritical. I’m just saying they’re overplaying their hand by celebrating his focus on reining in the super-rich as the only way that we can talk about improving economic equality.

ELAINE KAMARCK: This is part of a bigger problem with American presidential politics selling snake oil to the voters. Everybody from Trump with his stupid fucking wall, to Sanders with, “Oh, free college for everybody.” Of all the dumb things—let’s go ahead and give all the rich kids in America a nice break. That’s not progressive, I’m sorry. But people want to believe in Peter Pan. And he’s just not there.

Mark Green, former public advocate of New York and author of Bright, Infinite Future: A Generational Memoir on the Progressive Rise: There’s a lot of adrenaline in primaries between purity and plausibility. Sanders is the most popular insurgent in American history to get this close to a nomination, and to help define the Democratic agenda. I admire his guts to run in the first place, and I get why his combination of Bulworth and Eugene Debs makes him such an appealing candidate. But the programmatic differences between a walking wish list like Sanders and a pragmatic progressive like Clinton are dwarfed by the differences between either of them and the first proto-fascist president.

There’s a double standard against Hillary

Jill Filipovic: The dovetailing of gender and wealth in this election is really striking. I don’t remember a lot of Democrats ripping John Kerry to shreds for being wealthy when he ran for president. But it’s been interesting to see Clinton demonized for her Goldman Sachs speeches. For some Democrats, that seems to be inherently disqualifying. Obviously, money would be an issue even if she were a male candidate, because this is an election that’s about income inequality. But the sense that she’s somehow undeserving, that does strike me as gendered.

Theda Skocpol: Older women support Clinton because they’ve witnessed her career, and she’s always been into economic redistribution. Some Sanders followers have been quite sexist in things they’ve said; that’s very apparent to older women. A friend who studies abortion politics tells me that the nasty tweets she’s gotten from Bernie supporters for backing Hillary are worse than anything she gets from the right wing.

Amanda Marcotte, politics writer for Salon:What you’re seeing is a huge drift in the party, away from having our leadership be just a bunch of white men who claim to speak for everybody else. We’re moving to a party that puts women’s interests at the center, that considers the votes of people of color just as valuable as the votes of white people. Unfortunately, some of the support for Sanders comes from people who are uncomfortable with that change and are looking to a benevolent, white patriarch to save them.

ELAINE KAMARCK: Clinton is being penalized because she has a realistic view of what can be done, and that leads people to mistake her for some kind of bad conservative. She’s not. She’s extraordinarily liberal, particularly on children and families. But because she’s been around a while, when Sanders comes out with this new radical stuff, they think, “Oh, he’s the one whose heart is in the right place.” But listen, she took on Wall Street before he did, in a way that hit their bottom line. If people really want to get something done, they’d vote for her.

Mark Green: Look, there’s a debate I have with my friend Ralph Nader. He sees Hillary as more Wall Street, and I see her as more Wellesley. She’s as smart as anyone, grounded, practical, engaging, and unlike most testosterone-fueled male politicians, actually listens more than lectures. So she’s not as dynamic a candidate as Bill and Barack? Who is? That’s an unfair comparison. But if I had to bet, I’d guess she’ll be as consequential and good a president as either of them.

Poverty is fueling the divide

By Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

The Democratic Party today engages in delusional happy talk about economic recovery, while a staggering 47 million Americans are struggling in poverty. As the rich remain as wealthy as ever, working-class people continue to see their wages stagnate. In the 1970s, 61 percent of Americans fell into that vague but stable category of “middle class.” Today that number has fallen to 50 percent. African Americans, the core of the Democratic Party base, continue to be plagued by dead-end jobs and diminished prospects. Fifty-four percent of black workers make less than $15 an hour. Thirty-eight percent of black children live in poverty. More than a quarter of black households battle with hunger.

This is the heart of the crisis within the Democratic Party. Eight years ago, the party ran on hope: “Yes, we can” and “Change we can believe in.” Pundits openly wondered whether the United States was on the cusp of becoming a “postracial” nation; on the eve of Obama’s first inauguration, 69 percent of black Americans believed that Martin Luther King’s “dream” had been fulfilled. Today, the tune is quite different: Millions of Americans are more disillusioned and cynical than ever about the ability of the state to provide a decent life for them and their families.

Bernie Sanders tapped into the palpable disgust at America’s new Gilded Age, and it’s a revulsion that will not be quieted with a few platitudes from Hillary Clinton to “give the middle class a raise.” Yet the Democratic leadership continues to treat Sanders as an unfortunate nuisance. The party keeps charging ahead the way it always has, as Clinton pivots to her right to appeal to disgruntled Republican voters. As long as the party has no challengers to its left, the thinking goes, its base has nowhere else to go.

This strategy may lead Clinton to victory in November. But there is a danger here: In winning the battle, she very well may lose the war being waged within the Democratic ranks. The inattention to growing inequality, racial injustice, and deteriorating quality of life will likely result in ordinary people voting with their feet and simply opting out of the coming election, and future ones as well. Millions of Americans already do not vote, because most elected officials are out of touch with their daily struggles, and because there is little correlation between voting and an improvement in their lives. By continuing to ignore the issues Sanders has raised, Clinton and the rest of the party establishment risk losing a huge swath of the Democratic electorate for years to come.

There is a way out. More and more voters are identifying as independents. This demonstrates that people want real choices—as opposed to politics driven by sound bites, political action committees, and billionaire candidates. The wide support for both Sanders and Trump points to the incredible vacuum that exists in organized politics. If the movements against police racism and violence were to combine with the growing activism among the disaffected, from low-wage workers to housing advocates, we could build a political party that actually represents the interests of the poor and working class, and leave the Democrats and the Republicans to the plutocrats who already own both parties’ hearts and minds.

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, an assistant professor at Princeton, Is the author of From #blacklivesmatter to Black Liberation.

It’s the economy, stupid

John Judis: There have been insurgencies before—George Wallace in ’64 and ’72—that were radical. What made Wallace radical was the split in the party over civil rights. What makes Sanders radical is the lingering rage over the Great Recession.

If you want to move the question up a level theoretically, you can talk about the failure of “new Democrat” politics to deliver prosperity or economy security. Clinton and the Democrats in Washington don’t understand the level of anxiety that Americans, and particularly the young, feel about their economic prospects. It can’t be addressed by charts showing the drop in the unemployment rate.

Brett Flehinger, historian at Harvard and author of The 1912 Election and the Power of Progressivism: The Democratic Party has done a poor job of delivering on the economic promises of equality. That’s what’s opened up the possibility for Sanders. It’s what he’s believed in for 20-plus years. But the question is: What’s making it resonate now? It’s the failure of the party to liberalize, since Bill Clinton.

Jacob Hacker: There’s a feeling of, “Really? This is it? This is the recovery we’ve been promised?” It’s been a long, difficult path since 2008 and the financial crisis. Even Democratic voters who are doing pretty well are feeling that something has gone seriously awry.

This may be the first time in my life that there’s been a full-throated critique of the Democratic Party as being excessively beholden to money and too willing to work within the system. You saw echoes of this in the Howard Dean campaign, and you saw it much more forcefully in 2000 with Ralph Nader. But Nader was not running within the Democratic Party; he was clearly playing a spoiler role. Whereas Sanders is essentially trying to take the Democratic Party in a different direction.

Jedediah purdy: Bernie’s campaign is the first to put class politics at its center. Not poverty, which liberal elites have always been comfortable addressing, and not “We are the 99 percent,” which is populist in a more fantastical sense, but class more concretely: the jobs and communities of blue-collar people, the decline of the middle class, the cost of education.

Mark Hugo Lopez, director of Hispanic research at the Pew Research Center: When you ask Clinton supporters, or people who see Clinton favorably, you’ll find that more than half will say that, compared to 50 years ago, life is better in America today. Whereas among Sanders supporters, one-third will say that things are actually worse.

Democrats are too fixated on white workers

Jill Filipovic: The class-based concerns that a lot of the loudest voices in the Sanders contingent of the Democratic Party focus on are the concerns of the white working class, and they aren’t bringing a lot of race analysis into it. The income-inequality argument makes a case, particularly to the white working class, in a way that seems to have alienated African Americans and, to a lesser extent, the Hispanic vote.

Mychal Denzel Smith: Look at every demographic breakdown of who votes. The strongest Democratic Party voters are black women. So why is it that you’re so zeroed in and focused on regaining the white working-class vote? What value does that have to you, as opposed to appeasing the voters that are actually there for you? Democrats want it both ways. They want to attract the white working-class voter again, but what they don’t accept is that the reason they lost that voter is because of Republican appeals to racism. So the Democrats want to be the party of anti-racism but also win back the racists. You can’t do that! Why would you want a coalition of those people? It doesn’t make sense.

Democrats have neglected white workers

David Simon: There’s certainly something unique about this moment, and the populist rebellion that has affected both the Republican and Democratic parties. And I think it’s earned. Both parties can be rightly accused, not to the same degree, of having ignored and abandoned the working class and the middle-middle class for the past 30 years.

Millennials of color are tired of waiting

Alan Abramowitz, professor of political science at Emory and author of The Polarized Public? Why American Government Is So Dysfunctional: Why are African Americans so loyal to the Clintons? Part of it is just familiarity. They feel a comfort level with the Clintons, and they really like Bill Clinton, especially older African American voters. But there’s a generational divide even among African American voters. Younger African Americans and Latinos are not as supportive of Clinton.

Mark Hugo Lopez: I was in Chicago recently, and I was surprised when a young Latina college student stood up and described how much she did not like Clinton. She actually said, “I hate Hillary Clinton.” That’s the phrase she used, which drew a round of applause from everybody in the room.

Johnetta Elzie, a leader of Black Lives Matter: I don’t think anyone was ready to deal with black millennials. I just don’t believe that anyone in politics who is running on a national scale knows how to address young black or brown people in a way that’s different from how they addressed our elders. Because we’re not the same.

I remember when Hillary got shut down by some young black students in Atlanta. They wanted to know, “What does she even know about young black people in this neighborhood and what we go through?” John Lewis basically told them, “You need to wait to speak to Hillary. Just be polite, ask questions, yada yada.” And people were like, “But you were a protester before you were a politician! You know what it is, you know the sense of urgency, you know what it means to be told to wait and to know that we don’t have time to wait.”

Mychal Denzel Smith: Throughout our history, progressive movements have often left out the idea of ending racism. Then they go to communities of color and say, “What choice do you have but to join with us—to put aside your concerns about the differences that we experience in terms of racism?” In this election, the movement on the ground has at least pushed Democrats to adopt the language of anti-racism. They’ve had to say things like “institutionalized racism”—they’re learning the language on the fly. The problem is, they understand that they don’t actually have to move on these issues, because they have Trump to run against. All they have to do is say, “Look at how crazy the other option is. Where else are you going to go?”

Authenticity is gender biased

By Rivka Galchen

In an early scene in Stendhal’s The Red and the Black, a carpenter’s son hired as a tutor for a wealthy family dons a tailored black suit provided by his new employer. The black suit was a new and radical thing in this era, one in which bakers dressed like bakers, nobility like nobility. In a black suit, one’s social class was cloaked—a form of what back then was often termed hypocrisy.

Lately, as I’ve followed the contest between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, I’ve found myself thinking of The Red and the Black, and its play with antiquated notions of authenticity. The passionate support for Sanders has, one hopes, much to do with excitement about his insistent expression of a platform of economic populism. But it would be naïve to think it doesn’t also have to do with his appearance, his way of speaking. There is authenticity, and there is appearing authentic. These two things may mostly align—as they largely but not entirely do with Sanders. (Most anti-establishment figures avoid 35 years in government.) Or they may almost perfectly not align—as in the case of Donald Trump. (A liar celebrated for speaking the truth.) Either way, it’s worth investigating authenticity in our political thinking, both to understand its power and to consider how it helps or hurts the kind of effective, forward-looking agenda that we hope will emerge from a fractured Democratic Party.

One problem with authenticity as a campaign tactic is its unsettling, subconscious alliance with those who benefit from the status quo. If you’re not who you say you are—if you’re moving on the social ladder, or are not in “your place”—you’re inauthentic. Keeping it real subtly advocates for keeping it just like it is.

The semiotics of Sanders’s political authenticity—dishevelment, raised voice, being unyielding—are available to male politicians in a way they are not to women (and to whites in a way they are not to blacks or Hispanics or Asians). Black women in politics don’t have the option to wear their hair “natural”; nearly all white women appear to have blowouts, even Elizabeth Warren. It’s nonsense, and yet the only politically viable option, and therefore not nonsense.

It’s not just that research has shown that women are perceived to talk too much even when they talk less, or that men who display anger are influential while women who do so are not. It’s that there is no such thing as “masculine wiles.” The phrase just doesn’t exist. This doesn’t mean that calling into question Clinton’s authenticity and trustworthiness—the fault line along which the Democratic Party has riven—is pure misogyny. It just means that it’s not purely not misogyny.

Clinton is often described as the institutional candidate, the establishment. There’s a lot of truth to that. But she’s also the woman who initially kept her name (and her job) as the wife of the governor of Arkansas, who used the role of First Lady as cover to push for socialized health care, and who was instrumental in getting health insurance for eight million children past the Republican gorgons when a full reform failed. Someone who has survived being attacked for nearly 40 years must possess a highly developed sense of what the critic Walter Benjamin calls “cunning and high spirits”—the means by which figures in fairy tales evade the oppressive forces of myth, and mortals evade gods. Somehow she achieved one of the more liberal voting records in the Senate, despite rarely being described as a liberal by either the left or the right.

Perhaps one reason that Clinton’s “firewall” of black support has remained standing is that “authenticity” has less rhetorical force with a historically oppressed people, for whom that strategy—being recognizably who people in power think you ought to be—was never viable. There are, of course, important and substantial criticisms of Clinton. But perhaps when we say that Hillary is inauthentic, we’re simply saying that she is a woman working in the public eye.

Democrats on both sides of the party should consider which tactic best suits the underdogs they feel they are defending, and want to defend. Whoever receives the nomination, perhaps the worry should shift from whether the candidate is cunning to whether the candidate—and the Democratic Party—can be cunning enough.

Rivka Galchen is a novelist and essayist whose most recent book is Little Labors.

The disruption is digital

By Zeynep Tufekci

Insurgents like Bernie Sanders have been the rule, not the exception, in the modern era of Democratic politics. From Eugene McCarthy to Jesse Jackson, the party’s left wing regularly broke ranks to run on quasi-social democratic platforms. But with the exception of George McGovern in 1972, these challengers all fell short of the nomination, partly because they lacked the money to effectively organize and advertise. The party establishment had a virtual monopoly on every political tool needed to win.

Slowly at first—and then with a big, loud bang—digital technologies changed all that. First came Howard Dean, who used the internet to “disrupt” the Democratic Party in 2004. Powered by small online donations and digitally organized neighborhood “meetups,” Dean outraised his big-money rivals and revolutionized the way political campaigns are funded. Four years later, Barack Obama added a digitally fueled ground game to Dean’s fund-raising innovations, creating a campaign machine that could identify and turn out voters with a new level of accuracy. But when Obama’s policies fell short of the left’s expectations, many turned their energies to building a different kind of digital rebellion—this time, outside of electoral politics.

Sparked by a single email in June 2011, Occupy Wall Street exploded in a matter of months into a worldwide movement that mobilized massive street protests—including many who’d sworn off partisan politics as hopelessly corrupted. Occupy demonstrated how the masses could organize without a campaign or a candidate to rally around, opening a space that would soon be joined by Black Lives Matter and other activist groups. It also unleashed a populist fervor on the left. As the 2016 campaign approached, Occupy veterans joined forces with left-leaning activists inside the party. Instead of rejecting traditional politics, they decided to disrupt the Democratic primaries, the way Tea Party activists did to the GOP in 2010 and 2012.

In some ways, it didn’t matter that Sanders was the candidate they rallied behind. His ideological consistency earned him the trust of the left, and they in turn stoked his online fund-raising—producing the flood of $27 average donations that kept him competitive with Hillary Clinton. In the spirit of Occupy, Sanders’s digital operation was more volunteer-driven and dispersed than Obama’s; instead of “Big Data,” the watchword for Sanders was “Big Organizing,” as hundreds of thousands of volunteers effectively ran major parts of the show. A pro-Sanders Reddit group attracted almost a quarter-million subscribers, who helped organize everything from voter-registration drives to phone banks. A legion of young, pro-Sanders coders on Slack produced apps to mobilize volunteers and direct voters to the polls. There was even a BernieBNB app, where people could offer their spare couches to #FeelTheBern organizers.

Ultimately, the Sanders campaign became a lesson in both the potential and the limitations of a digitally fueled uprising. It seems miraculous that a 74-year-old democratic socialist could come so close to beating a candidate with Clinton’s institutional advantages. But Sanders’s superior digital reach couldn’t help him win over African Americans and older women, most of whom favor Clinton. And all his fans on social media could not alter the mainstream media’s narrative that this was yet another noble but doomed insurgency.

Whether or not Clinton wins in November, it’s safe to expect another Democratic insurgency in 2020—and beyond. Digital fund-raising, organizing, and messaging have given the left the weapons not just to tilt at the establishment’s windmills, but to come close to toppling them. Next time, they might just succeed.

Zeynep Tufekci studies technology’s social impacts at the University of North Carolina.

Split? What split?

Ruy Teixeira: I don’t see differences massive enough to provoke any kind of split that has serious consequences. It’s just part of an ongoing shift in the Democratic Party. The party is going to continue to consolidate behind a more aggressive and liberal program, and the Sanders people are a reflection of that. We shouldn’t lose track of the fact that Clinton will be the most liberal presidential candidate the Democrats have run since George McGovern.

Brett Flehinger: In historic terms I don’t think this party is split. I don’t even think the divide is as big as it was in 2000, when a significant portion of Democratic voters either considered Ralph Nader or voted for Nader.

Alan Abramowitz: It’s easy to overstate how substantial the divide is. Some of it is more a matter of style, the sense that Clinton and some of these longtime party leaders are tainted by their ties to Wall Street and big money. But it’s not based so much on their issue positions, because Clinton’s issue positions are pretty liberal. Not as far left as Bernie—but then, nobody’s as far left as Bernie. Part of it is a distortion, because you can’t get to Bernie’s left, except maybe on the guns issue. So Bernie can always be the one taking the purist position.

Theda Skocpol: This isn’t a revolution. The phenomenon of having a left challenger to somebody called an establishment Democrat goes way back. It’s been happening my whole life, and I’m not a child. It’s never successful, except in the case of Obama. And Obama had something that the other challengers didn’t: He was able to appeal to blacks. Most of these left candidates appeal to white liberals, and Sanders is certainly in that category. His entire base is white liberals.

Kevin Baker, author of the novel Strivers Row: Democrats have almost always been the party that co-opts and brings in literal outsiders and outside movements. In the late nineteenth century, it was a bizarre coalition between Southern bourbon planters and big-city machines, which each had their own grievances. Then it was an uneasy coalition between those same machines and the agrarian populists brought in by William Jennings Bryan. Then you had the Grand Coalition, the biggest, most diverse coalition in American history, which was the New Deal one: farmers and workers, urbanites and Main Street progressives, blacks, whites, feminists, unionists. It lasted a long time, until it broke down over race and the Vietnam War in the 1960s. Finally, you had the rise of the Democratic Leadership Council and the Clinton-ite and Obama-ite version of more conservative progressivism. But what that coalition left unanswered, for a lot of people in the party and in the country, was just how they were going to make a living in this new world. What we’re seeing now is a very civil contest, relatively speaking, over who is going to lead that coalition.

Don’t worry: Trump will unite us

John Judis: Whatever shortcomings Clinton’s campaign has in creating unity are likely to be overcome by the specter of a Trump America.

Ruy Teixeira: I don’t see the people who support Sanders, particularly the young people, as being radically different from the Clinton folks in terms of what they support. They’ll wind up voting for Hillary when she runs against Trump.

David Simon: If you’re asking me if I think the Democratic Party will heal in the general election, I think it will. Trump helps that a lot. The risks of folding your arms and walking away are fundamental, in a way they might not be with a more viable and coherent candidate. But let’s face it, the idea of this man at the helm of the republic is some scary shit.

Bernie isn’t the future, but his politics are

Alan Abramowitz: Younger voters are the future of the Democratic Party. But Bernie Sanders is not the future of the Democratic Party. The question is: Who’s going to come along who can tap into that combination of idealism and discontent that he represents?

john Judis: Sanders is an old guy, like I am, and not one, I suspect, to build a movement. And I think “movement” is probably the wrong word. What inspires movements is particular causes (Vietnam, civil rights, high taxes) or a party in power that is seen as taking the wrong stance on those issues (George W. Bush for liberals, Barack Obama for Republicans). If Clinton is the next president, I don’t expect a movement to spring up. Instead, I’d expect to see caucuses within the party that take a Bernie Sanders/Elizabeth Warren point of view. But if Trump wins, you will see a movement, whatever Sanders does.

Jacob Hacker: There’s a growing chunk of the Democratic electorate that believes the existing policy ideas that define the mainstream of the party don’t go far enough. The question becomes: What do those folks do after the election? What kind of force will they be within the party going forward? Can they form a strong movement that will press national politicians to move to the left, the way the Tea Party did on the right?

If a Democrat wins in November, you probably can’t get a movement like the Tea Party under Obama, or Move On under Bush. But what you could get—what you would hope to get—is a true grassroots, longer-term movement that tries to move the center of gravity of American politics to the left.

Jedediah Purdy: But what would a movement built out of Sanders supporters be for, exactly? The campaign itself gives some answers. The Sanders campaign is much more distinct from the Clinton campaign, in substance, than Obama’s first campaign was. The Fight for $15, single-payer health care, stronger antitrust law, free college: These are huge, concrete goals. If people can organize around one guy who expresses them but, if elected, could do very little unless we also changed Congress, then we should be able to organize around them to try to change the makeup of political structures from top to bottom. Maybe we need to move into our local Democratic parties. The Moral Majority took over school boards with a specific agenda they could implement. Are there electoral institutions, as well as party institutions, that we should be aiming to reshape in our image?

Danielle Allen: It’s a huge opportunity for Democrats, if they can take all the incoming young participants seriously and give them a real role in digging into hard policy questions. This is a chance to cultivate leaders who can run for office across the landscape—not just national office, but local office. The Republicans have done a much better job, in all honesty, at growing up a generation of younger politicians. Democratic politicians skew older, so that sums up the real question about the Sanders moment: Is this enough of a wake-up call to the Democratic Party to start bringing talent in?

It’s a trap!

Astra Taylor: The young thing, this millennial left turn, is great. But there’s a part of me that’s afraid. In the 1960s, the story was the counterculture and the new left. It was Students for a Democratic Society, the civil rights movement, the war in Vietnam. But there’s been a lot of smart revisionist scholarship that says the story of the ’60s was not the new left, it was actually the new right, which spent the decade laying the groundwork for its resurgence. At this moment, when left-wing millennials are getting a lot of attention, my fear is that there’s a conservative counterpoint that I’m just not seeing, because we’re all in our little social and political bubbles. We should study the split between the new left and the new right in the ’60s, and make sure that history doesn’t repeat itself.

The worst thing would be to ignore the split

David Simon: The Democrats are going to win, because they’re up against Trump. But I’m worried they’re going to paper over a fundamental flaw in their coalition, which is: You’ve got to help working people and the middle-middle class. They’re not your guaranteed votes, and you lost them once to Reagan. Maybe you can do without them long-term. But I would get them back because (a) it secures your coalition going forward and (b) it’s the right thing to fucking do.

Jill Filipovic: The brawls that people are having on Twitter every day—I don’t know if that’s healthy for the party. But the bigger debates are really important conversations to be having. Who is our coalition? Who are we representing, and how do we best do that? Do we want to be the center-left party of the ’90s, or should we be serving a more diverse and liberal voter base? I don’t think those conversations are going to destroy the party. I think they’re going to set us in a better direction.

Jacob Hacker: It’s nice to be able to talk about what’s happening on the Democratic side, because all of the focus has been on the Republican side. It’s a bit like living in a house that’s got some peeling paint and holes in the roof. Right next to it is a derelict building that’s practically falling over. And you’re like, “Man, I’ve got a nice house.” But if you just put your hand up and cover up your neighbor’s house so you can’t see it, you’d be like, “Um, I think my house needs some work.” The Democratic Party is kind of like that right now. I want to live there, but I really would love to upgrade it.

The best is yet to come

By Naomi Klein

On the surface, the battle between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders looks like a deep rift, one that threatens to splinter the Democratic Party. But viewed in the sweep of history, it is evidence of something far more positive for the party’s base and beyond: not a rift but a shift—the first tremors of a profound ideological realignment from which a transformative new politics could emerge.

Many of Bernie’s closest advisers—and perhaps even Bernie himself—never imagined the campaign would do so well. And yet it did. The U.S. left—and not some pale imitation of it—actually tasted electoral victory, in state after state after state. The campaign came so close to winning that many of us allowed ourselves to imagine, if only for a few, furtive moments, what the world would look like with a President Sanders.

Even writing those words seems crazy. After all, the working assumption for decades has been that genuinely redistributive policies are so unpopular in the U.S. that they could only be smuggled past the American public if they were wrapped in some sort of centrist disguise. “Fee and dividend” instead of a carbon tax. “Health care reform” instead of universal public health care.

Only now it turns out that left ideas are popular just as they are, utterly unadorned. Really popular—and in the most pro-capitalist country in the world.

It’s not just that Sanders has won 20-plus contests, all while never disavowing his democratic socialism. It’s also that, to keep Sanders from hijacking the nomination, Clinton has been forced to pivot sharply to the left and disavow her own history as a market-friendly centrist. Even Donald Trump threw out the economic playbook entrenched since Reagan—coming out against corporate-friendly trade deals, vowing to protect what’s left of the social safety net, and railing against the influence of money in politics.

Taken together, the evidence is clear: The left just won. Forget the nomination—I mean the argument. Clinton, and the 40-year ideological campaign she represents, has lost the battle of ideas. The spell of neoliberalism has been broken, crushed under the weight of lived experience and a mountain of data.

What for decades was unsayable is now being said out loud—free college tuition, double the minimum wage, 100 percent renewable energy. And the crowds are cheering. With so much encouragement, who knows what’s next? Reparations for slavery and colonialism? A guaranteed annual income? Democratic worker co-ops as the centerpiece of a green jobs program? Why not? The intellectual fencing that has constrained the left’s imagination for so long is lying twisted on the ground.

This broad appetite for systemic change did not begin with Sanders. During the Obama years, a wave of radical new social movements emerged, from Occupy Wall Street and the Fight for $15 to #NoKXL and Black Lives Matter. Sanders harnessed much of this energy—but by no means all of it. His weaknesses reaching certain segments of black and Latino voters in the Democratic base are well known. And for some activists, Sanders has always felt too much like the past to get overly excited about.

Looking beyond this election cycle, this is actually good news. If Sanders could come this far, imagine what a left candidate who was unburdened by his weaknesses could do. A political coalition that started from the premise that economic inequality and climate destabilization are inextricable from systems of racial and gender hierarchy could well build a significantly larger tent than the Sanders campaign managed to erect.

And if that movement has a bold plan for humanizing and democratizing new technology networks and global systems of trade, then it will feel less like a blast from the past, and more like a path to an exciting, never-before-attempted future. Whether coming after one term of Hillary Clinton in 2020, or one term of Donald Trump, that combination—deeply diverse and insistently forward-looking—could well prove unbeatable.

Naomi Klein is the author of This Changes Everything and The Shock Doctrine.

COVER REFERENCE PHOTOS: JAMIE MCCARTHY/GETTY (SANDERS). MANUEL BALCE CENETA/AP (CLINTON)