It is often said of the writer Rebecca Solnit that her work “resonates.” It’s hard to find an article about her that doesn’t include that word. At a time when feminism is about finding others who have lived on the same frequency (#metoo, #yesallwomen), a thinker like Solnit, who gravitates toward identifying common denominators in the female experience (mansplaining, gaslighting, silencing, etc.) is primed to resonate.

Nowhere is resonance better measured than on social media, where Solnit’s work is shared and circulated expeditiously. On her Facebook page, which has over 150,000 followers, she shares news articles, political commentary, and posts that read like magazine essays; it has become an online community unto itself for feminists looking for digital platforms to express rage, hope, and everything in between. That her work feels tailor-made for the kind of collective experience social media enables is no coincidence. Solnit’s rise to new levels of fame stems from one of her essays, “Men Explain Things to Me,” going viral online. (She had in fact published nearly a dozen books by the time that essay appeared.) The piece, written originally for the Los Angeles Times, popularized the word mansplaining, a term that accomplished the rare feat of articulating a familiar but as-yet-unrecognized experience.

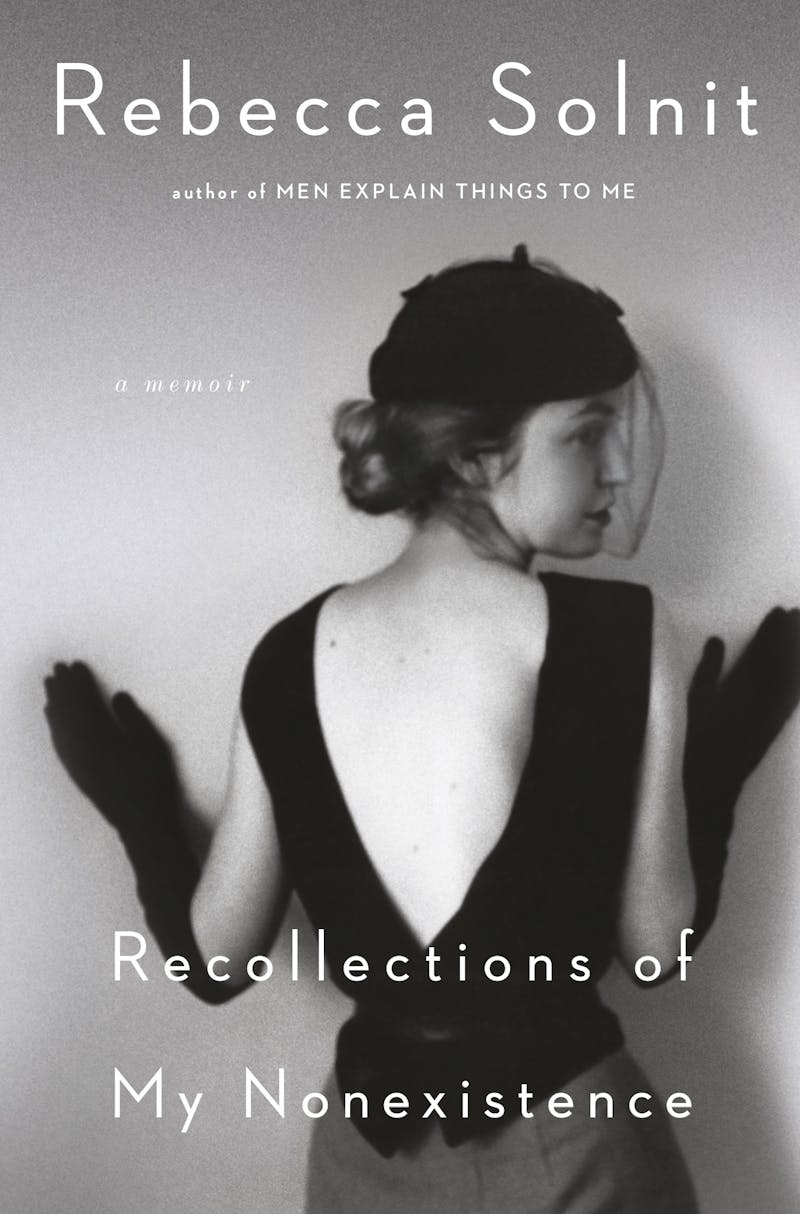

Solnit’s new book, Recollections of My Nonexistence, takes us to her formative years, when she was experiencing patterns of misogyny she could not name (and, as she explains, therefore could not fight). “I was often unaware of what and why I was resisting,” she reflects, “and so my defiance was murky, incoherent, erratic.” She came to see this condition, and that of all women, as a kind of imperative toward nonexistence. The book, a memoir and creative autobiography, is meant as an antidote, a guide to avoiding self-effacement in a world where women are routinely disappeared and quieted down. “I can wish that the young woman who came after me might skip some of the old obstacles,” she writes, “and some of my writing has been toward that end, at least by naming these obstacles.”

The memoir revisits many of the concepts—mansplaining, gaslighting, street harassment, the transformative power of women’s stories—that appear both in Solnit’s previous work and in the online feminist ecosystem that has supported it. The result feels perhaps too familiar, a book so focused on existing conversations, so tightly structured around relatable insights, that it feels—dare I say it—designed to do little more than resonate online.

Solnit grew up in a troubled household in a suburb of San Francisco. After a brief stint in Paris as a teenager, she returned to northern California where she took the GED at 15 and graduated from San Francisco State University in 1981 at age 20. The year before, she moved into an apartment in a predominately African American neighborhood near the city’s Panhandle district. “Later on I’d come to understand gentrification and the role that I likely played as a pale face making the neighborhood more palatable to other pale faces,” she writes, “but I had no sense at the start that things would change and how that worked.” Solnit would spend the next two decades in this studio apartment, writing near her bay window on a desk gifted to her by a friend who was nearly stabbed to death by an ex-boyfriend. “Now I wonder,” she reflects, “if everything I have ever written is a counterweight to that attempt to reduce a young woman to nothing.”

One of the strengths of the book is the way Solnit manages to think through nonexistence as both a weapon and a shield. In an early chapter, she writes about how she learned the “art of nonexistence” as a young teenager, trying to avoid the gaze of older men, including some in her own family. “At twelve and thirteen and fourteen and fifteen, I had been pursued and pressured for sex by adult men on the edge of my familial and social circles.” Throughout her adolescence and young adulthood, Solnit begins looking for ways to exist as little as possible, from turning thin to the point of frailty to becoming constantly aware of exits and escapes: “I became expert at fading and slipping and sneaking away, backing off, squirming out of tight situations … at gradually disengaging, or suddenly absenting myself.” Solnit often writes about her decision to become a writer as a desire to name the various violences that chased her. It is also possible that the life of an author—tucked away in archives, working quietly in writing nooks—presented a way to live a life physically out of view.

Nonexistence can also be literal for Solnit, as the chapter “Annihilators” makes clear. The 1970s and 1980s saw a spike in the number of serial killers, leading to a general sense of anxiety across the country, one most keenly felt by young women who were their primary targets. “It was the era” Solnit explains “of the Night Stalker and the middle-aged white man known as the Trailside Killer (who raped and killed women hikers on the trails I hiked on) and the Pillow-case Rapist and the Beauty Queen Killer and the Green River Killer and the Ski Mask Rapist and many other men who rampaged up and down the Pacific Coast without nicknames.” Solnit recalls a harrowing story of walking home following a New Year’s Party and being followed closely by a man on a dark, empty street. While she ultimately finds her way out of the situation, the trauma stays with her; it is one of the most detailed and specific memories that Solnit recalls from this period in her life.

Solnit is especially attuned to the normalization of violence against women in popular culture and belles lettres. In this way, Recollections of My Nonexistence is often closer to a work of cultural criticism than memoir—though in combining the two, it asks us to think about how much our sense of self-worth and social value is shaped by the cues we get from films, books, and television. “In the arts,” she notes, “the torture and death of a beautiful woman or a young woman or both was forever being portrayed as erotic, exciting, satisfying.” She alludes to the work of Alfred Hitchcock, Brian De Palma, and David Lynch, directors whose signature works centered on murdered women (Psycho, Twin Peaks, etc.): “Legions of women were being killed in movies, in songs, in novels, and in the world, and each death was a little wound, a little weight, a little message that it could have been me.” For Solnit, the aestheticization of these stories amounts to a kind of delegitimization of the very real fears she harbored at the time about her safety. It “was a kind of collective gaslighting” she writes, tantamount to “[living] in a war that no one around me would acknowledge as a war.”

It is hard to disagree with anything Solnit says here, but one wonders if that is a shortcoming. Though Solnit makes references, largely in asides, to the ways women’s experiences are complicated by race, class, and sexual orientation, there is little real mining of these disjunctures. In Recollections of My Nonexistence, women and minorities largely exist as innocent, interesting figures who add “vitality” to spaces, who fit neatly into Solnit’s worldview wherein misogyny is largely a thing that straight white men (and Kanye West) do.

She passes by black churches and revels in the idea that she is “never too far from devotion,” but does not consider the potential collision of Christian modesty with feminist ideas about sexual liberation. She writes that she likes living in California because it “faces Asia” but does not engage with the unique contours of Pacific feminism. The gay men in the Castro make great friends for Solnit—“Oh, how I was free to be funny or dramatic or preposterous around them,” she exclaims—but the capacity of queer men to enact misogyny is never explored.

A few years ago, Viviane Fairbank of The Walrus wrote a piece titled “Why I Don’t Read Rebecca Solnit,” that articulated some of the same anxieties I hold about Solnit’s relatively unquestioned status as an important voice in contemporary feminism. For Fairbank, Solnit’s writing embodies a new, watered-down ethos of feminist solidarity, “call it ‘pop feminism,’—that addresses only topics we can safely agree on.” Fairbank traces Solnit’s belief in the power of women’s stories to the consciousness-raising work of 1960s feminists, reminding us that these stories were meant to lead to “debate that triggers policy change, social reform, or even popular demonstrations. Solnit never makes it past anecdotal evidence.” Likewise, I kept waiting for this book to spin out more, to think, for instance, about how nonexistence functions under capitalism through the erasure of women’s labor, or what it means when women become not invisible but indeed hypervisible as justifications for military intervention (i.e., the U.S. government’s insistence that its invasion would “liberate” Afghan women).

While Solnit has written extensively elsewhere on climate and anti-nuclear activism, those issues often recede into the background in Recollections of My Nonexistence. There is a distinct lack of politics as policy here, perhaps because a truly feminist political vision might make some of Solnit’s white and upper-middle-class readers uncomfortable. But that is what happens when resonance is treated as an ethos in and of itself; we begin to silence ourselves, and solidarity becomes little more than a new kind of nonexistence.