That dance is evanescent might be its most significant aspect, just as it’s said that death gives meaning to life. But culture depends on preservation. This tension seems impossible to reconcile. We know Merce Cunningham was one of our great dancers and choreographers, but if we were born too late, or in the wrong place, or just weren’t paying attention, did we forever miss our chance to understand why?

Yes, we have video. Right now, at the Museum of Modern Art, you can watch Cunningham dance his 1964 Antic Meet, and it is of course a pleasure to watch him do so. But grainy archival evidence can’t really deliver transcendence, and who will pause in their museumgoing to absorb the full 27 minutes?

On the centenary of Cunningham’s birth, two works aim to honor the man and his art: Alla Kovgan’s documentary Cunningham and the epistolary collection Love, Icebox: Letters from John Cage to Merce Cunningham. Over the 50 years that Cunningham was active, he collaborated with leading figures in the arts (everyone from Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg to Radiohead and Rei Kawakubo). He trained younger dancers, his influence one of the clearest measures of his significance. Cunningham and his contemporaries came off as tricksters but prized clarity. His dances surely seemed as disorienting as those Rauschenbergs at first; it’s worth being reminded that the dances, too, were masterpieces.

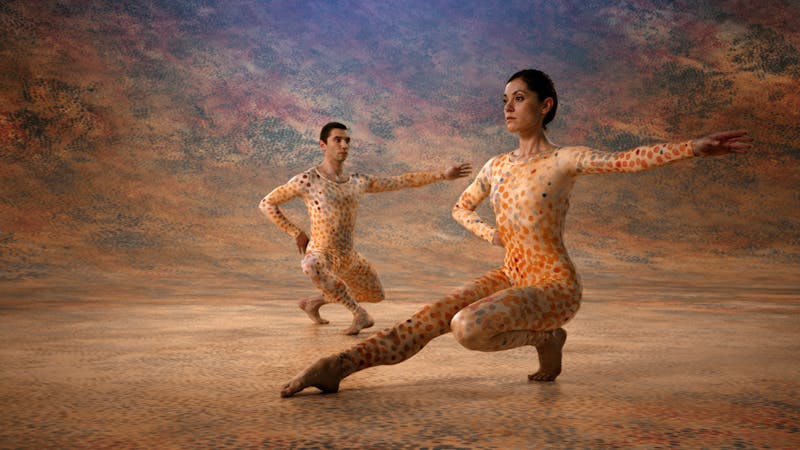

Cunningham is not quite a biographical portrait, though we do hear a bit from Cunningham himself, and there’s footage of his old performances. There is helpful context—here’s Cunningham with (speaking of tricksters) Andy Warhol, dancers moving through the pop artist’s helium-filled Silver Clouds; here he is making a splash on the London stage (imagine any modern dancer making a splash?). But Kovgan is creating a collage of sorts, the highlight of which is 3-D footage of contemporary dancers performing Cunningham’s choreography.

I find watching anything in 3-D disorienting (this might be simply because I wear eyeglasses, and having to sport two pairs for the length of a film is annoying), but it is a novel way to experience dance. The scale of the screen overwhelms, so these bodies are larger than you’d ever encounter in life. The camera is not passive, but dynamic, weaving between the performers; the viewer almost inhabits the perspective of Cunningham himself, appraising the work.

Kovgan shoots her dancers on a city rooftop, in a sunlit studio, in a verdant garden, against an exuberantly painted backdrop; these are less recreations than reinterpretations. Her argument is that Cunningham’s work still matters, and it’s left to the dancers to persuade us.

Maybe it’s more than a 90-minute film can accomplish. I wanted each dance sequence to be longer, to feel my mind drift away as it does when I’m seated in an auditorium. At one point, Cunningham explains the dancer’s task: “We don’t interpret something. We do something.” He argued for a dance that was a visual experience, like painting. I like the intellectual rigor of this assertion—it feels so high Modern—but it’s obviously not quite the truth. We look at Cunningham’s dancers in motion and see birds on the shore or human gestures of love, joy, anger. We hear the music of Satie or John Cage, and it sounds either beautiful or sinister, soothing or strange.

We sit in the audience, enthralled or bored, and ask ourselves: What does it all mean? That’s the nature of interacting with art. When I watch dance, comprehension feels elusive, maybe because I don’t see dance often enough or know what I’m meant to be looking for. But it’s all the more difficult to arrive at your own interpretation when you only experience the dance in snippets.

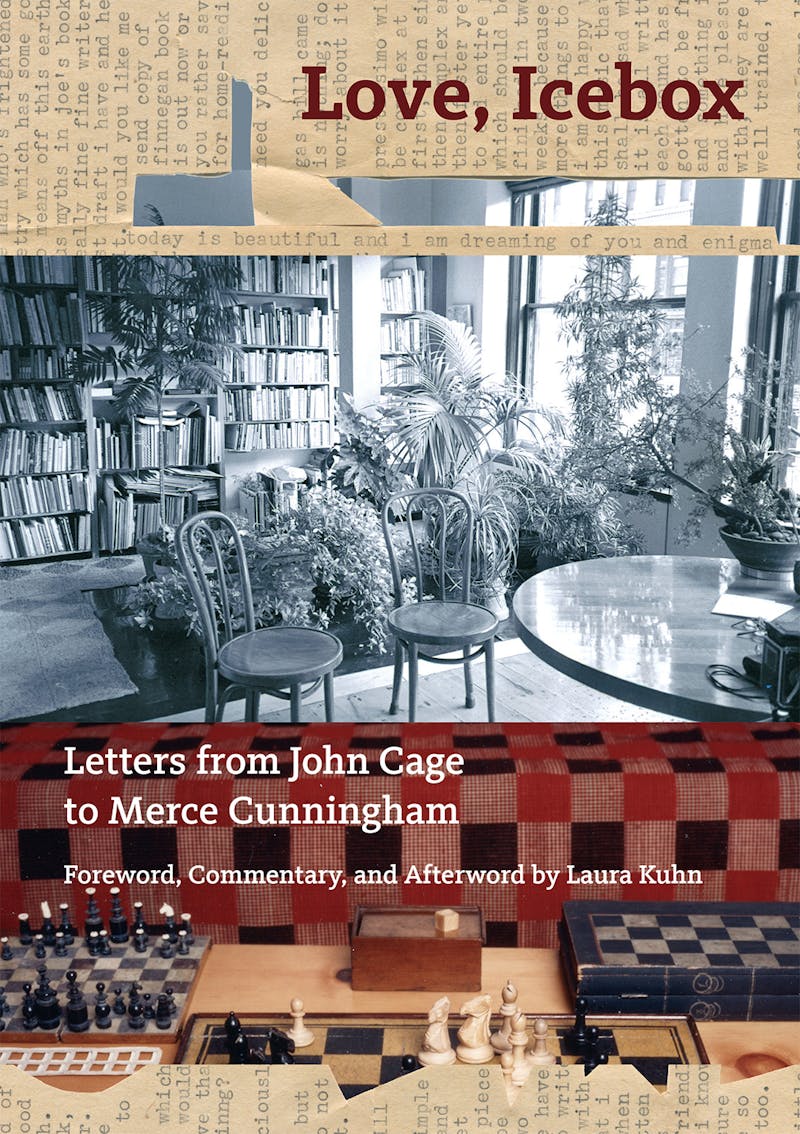

If Kovgan’s movie aims to give us Cunningham the artist, Love, Icebox gives us a bit more of Cunningham the man. Assembled by Laura Kuhn, the director of the John Cage Trust and a trustee of the Merce Cunningham Trust, the book is an intimate look inside the long-standing romantic and creative collaboration between two of the titans of the Modernist avant-garde: Merce, the fierce dancer, and John, the cerebral composer.

If Kovgan’s documentary shows us Cunningham’s fame, Kuhn’s book tells us how audiences might not have known the men’s partnership to be a romantic one, despite it being well understood among their circle. There is a sense that they were predisposed to being private but were also simply held hostage to the mores of their time.

One of the most delightful things about the letters is how horny they are. In one, Cage refers to his own penis as “enigma,” and Cunningham’s as “his little friend.” Cage adds a postscript to a 1943 missive: “Starved for a good long fuck with you,” then worries, “Maybe you’re getting angry or disgusted because I write too full of desire and getting sexy.” But he can’t help himself, closing with, “I am in oestrus now thinking of you—such a full-fledged need.”

We only hear from Cage on these pages, a person who turns out to be so far from my perception of him based on his work, with its interest in cool mathematics or chance and accident. There’s passion here, and even if the men were private, they’re our queer ancestors, so it’s nice to see that passion entered into the record. The letters tell us about Cunningham insofar as he’s the beloved, therefore both their audience and their object. In an early letter, Cage flatters: “I was amazed that the reviews didn’t headline your work. But they didn’t. No one recognizes Nijinsky when they see him.” Is this an attempt at seduction, or was Cunningham the greatest of our dancers?

I accept that he was, even if this is maddeningly hard to judge. Maybe the loveliest thing about Love, Icebox is its art. The book is punctuated with snapshots of the couple’s 18th Street loft, which looks just as you’d expect it to: flooded with light, full of houseplants, crammed with art and papers and meaningful bric-a-brac, the kind of New York homestead that seems only to live on in simulacra, as art-directed television location.

This film and this book are meant only to supplement the work that Cunningham created. The ghosts of that work haunt the internet, and his namesake trust is devoted to ensuring it’s still performed and that dancers are educated in Cunningham’s favored techniques. Still, you have to accept that the work fundamentally died with Cunningham, in 2009. An artist this great gets something close to immortality—these aren’t the first and won’t be the last testaments to him. But this is just how it goes: We know the name of this dancer, but dance is meant to disappear.