On a spring evening in 1955, Gwen Verdon and Bob Fosse met for the first time. She was the bigger star of the two, but technically he held much of the power. She was a famous Broadway dancer and actress from Culver City, California, who had worked her way up from the chorus line to the lead; with her corona of red curls and an overdose of natural comedic timing, she was an irrepressible talent. In 1954, she won her first Tony Award, for playing the role of Eve in a ballet number about the Garden of Eden in Cole Porter’s Can-Can. Her Tony was something of a surprise; Verdon’s co-star in Can-Can, the French actress Lilo, was allegedly so jealous of Verdon’s charisma that she demanded that Verdon’s part be cut down after the out-of-town previews. Wounded by this slight, Verdon announced that she was quitting the show, and possibly dancing altogether. Still, she gave the performance, and, according to The New York Times, “She was already back in her dressing room for a costume change when one of the producers came pounding in to tell her that the audience was chanting her name and cheering.”

Bob Fosse was a young choreographer, fresh off his first Broadway show, The Pajama Game. The producer Hal Prince hired him to choreograph Damn Yankees, a Faustian musical about a man who makes a deal with the devil to become a baseball champ, and told Fosse that he wanted to cast Verdon as Lola, an irresistible temptress who had been a plain woman before she, too, sold her soul. Fosse was not sure, however, that Verdon was up to the task. The key to playing Lola was not just kittenish sex appeal, but also a wry world-weariness; she got the immortal youth she desired, but learned that seducing men for hundreds of years is exhausting work. Fosse needed to be sure that Verdon could really sell Lola’s ironic detachment to the audience. So Prince scheduled an audition.

The two dancers met after dark at Walton’s Warehouse, a rehearsal space in midtown Manhattan. According to Sam Wasson, whose biography, Fosse, appeared in 2013,

she saw a crumpled, soft-talking dance tramp, and he saw the sweetest, hottest dancing comedienne of the age. One with a reputation. Underneath her smile, he had heard, Verdon could be a difficult collaborator, a high-class snob with an ironclad pedigree and an almost pathological aversion to the kind of heigh-ho Broadway jumping around she called animated wallpaper.

Which is to say: Both sashayed into the room with high standards. Verdon, who had already been working as a junior choreographer for years as an assistant to the Broadway legend Jack Cole (his work included Kismet and Man of La Mancha), had her own ideas about what constituted interesting dancing. Because she was a woman, and it was 1955, this made her “difficult.” Fosse was stubborn, picky, and precise. Because he was a man, and it was 1955, this made him a rising star.

We can never really know exactly what happened the first night that Fosse and Verdon met; we only have the spoils of their collaboration. Damn Yankees ran for 1,019 performances. Verdon won her second Tony, appearing on the cover of the cast album in a tight black leotard and sheer thigh-high stockings. Her big number, “Whatever Lola Wants (Lola Gets),” when she performs a striptease in the baseball locker room, became an instant classic, a routine that future dancers would study for its fine line between seduction and humor. Fosse, who was married to the dancer Joan McCracken when he started working on Damn Yankees, entered into a romantic affair with Verdon and ultimately left his wife for her. By 1960, the pair were married, and in 1963, Verdon gave birth to their daughter, Nicole. The two were true creative partners: Although Fosse came up with the ideas for his jerky, hyper-specific movements (“Bob choreographs down to the second joint of your little finger,” Verdon once said), Verdon’s innate playfulness and deep well of technical knowledge helped Fosse’s steps come alive on the stage. They had a rare creative symbiosis, an electric synergy.

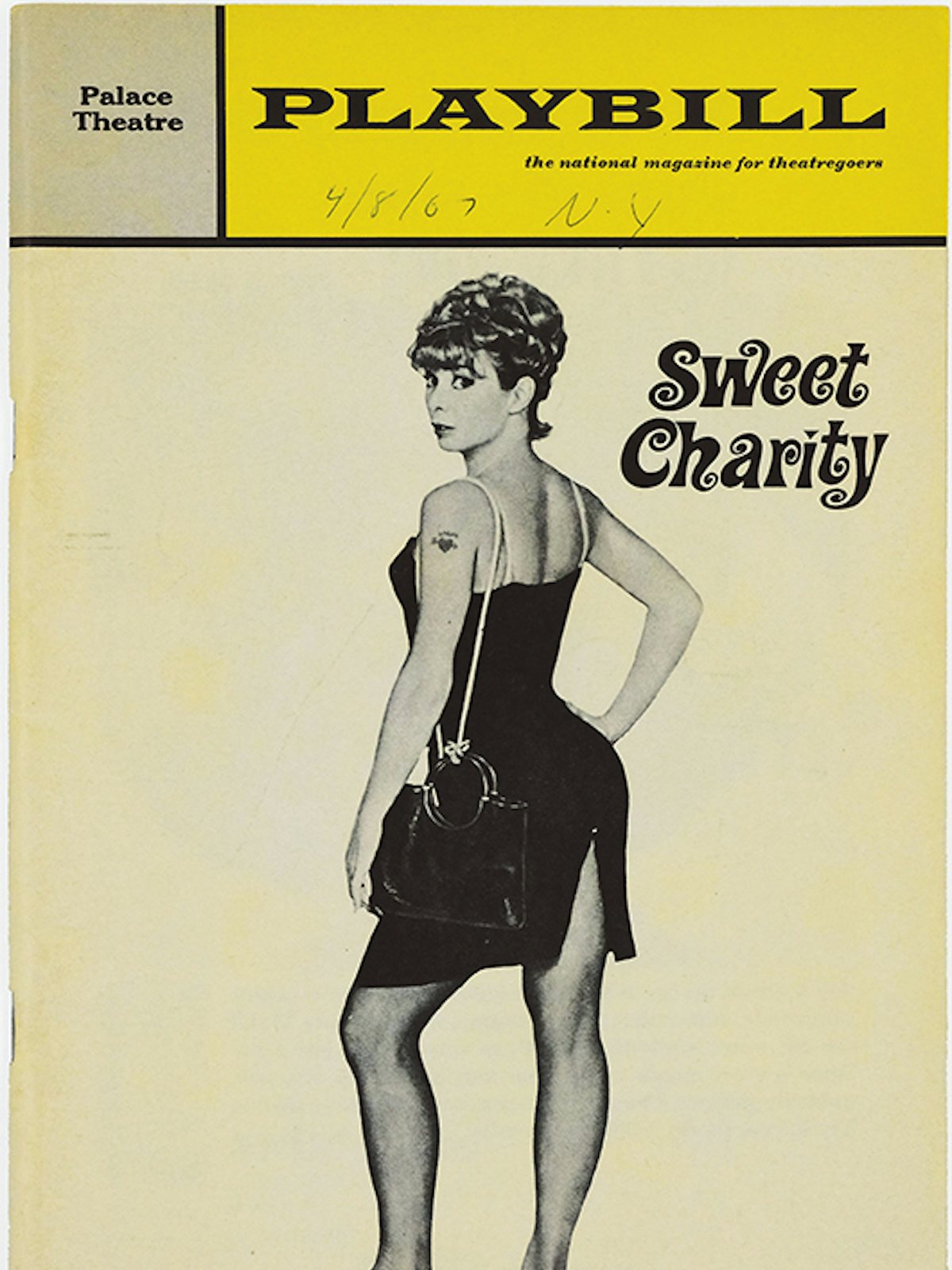

And yet despite Verdon’s magnetic power, she has receded from history, while Fosse’s legacy has been cemented and celebrated several times over. In 1969, Fosse made the leap from Broadway to Hollywood, directing his first film, an adaptation of the stage musical Sweet Charity. Verdon played the lead role (a gutsy hostess in a New York dance hall) in the musical on Broadway and received raves, but the producers at Universal thought they needed a more bankable (and younger) name to carry off the screen version and brought in Shirley MacLaine. As Fosse’s wife, Verdon still lent her skills to the film, providing the choreography for iconic numbers like “Big Spender.” Fosse’s infidelities led the pair to separate, but they kept working together. Verdon originated the role of Roxie Hart in Chicago on Broadway, and she also worked with him on two later projects, Dancin’ and All That Jazz.

Fosse gets much of the credit for infusing Broadway with his sleek, fastidious style, all those little fist pops, hat tips, and hip isolations that became his signature. In 1999, the musical Fosse, an homage to his greatest numbers, opened on Broadway. Co-directed and choreographed by Ann Reinking, Fosse’s romantic and creative partner after Verdon (and her replacement as Roxie in the Broadway revival), the show contributed to the legend of Fosse as a solo genius, the singular visionary of the toe flick. But Verdon was also involved; she served as the artistic adviser on the show, one of her last acts before she died in 2000. When she reflected on her life, she often credited Fosse extravagantly with drawing her talent out of her. “I was a great dancer when he got hold of me, but he developed me, he created me,” she said.

What she did not say was that she also created him—she held up his mythology, she propagated it. They were locked, for better or worse, in an endless mambo, even as one of the partners was spinning out of the spotlight.

Film and television have lately brought a new rush of women’s stories into the foreground, particularly in period pieces; there’s The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Hidden Figures, The Favourite, Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Feud: Bette and Joan. Several more shows that attempt to recover forgotten or distant women are in development for television: a comedic version of Emily Dickinson’s youth, starring Hailee Steinfeld; a Netflix drama starring Octavia Spencer as Madam C.J. Walker, a black beauty entrepreneur in the early 1900s. There is an urgency to these stories, which both serve as a corrective and make good business sense. Hollywood has finally realized that women’s stories can sell too.

What makes Fosse/Verdon, a new eight-part miniseries airing on FX, an interesting spin on this formula is that it is only half a woman’s story. It really is a biography of a love affair (adapted primarily from Wasson’s biography) that attempts to split its sympathies between its characters: In the stylized, Vaseline-lensed world of the show, Fosse (Sam Rockwell) is indeed a maverick, a bad boy of the theatrical establishment whose jazz hands are just too hot for the critics to comprehend. Verdon (a captivating Michelle Williams, doing her best trans-Atlantic accent) is a radiant performer, who is also a long-suffering amanuensis, the devoted wife who puts up for years with her husband’s philandering because she believes he still brings out the best in her. It is clear that the director, Thomas Kail, who also directed the Broadway musical Hamilton (Hamilton’s creator and star, Lin-Manuel Miranda, is an executive producer on Fosse/Verdon), wanted to tell both sides of the story—the tortured maestro, his beleaguered muse. Yet, at least in the show’s early episodes, his take on the story is more style than substance, a razzle-dazzle gloss over twisty, messy lives, an occasion for a sparkly musical extravaganza rather than an attempt to plumb the depths of co-dependent creativity.

What this means is that Fosse/Verdon, as a period piece, is undeniably beautiful. Every detail is exquisitely correct, down to the way a dancer holds her entire leg on a brass beam during the opening moments of the pilot, when Verdon is choreographing “Big Spender.” This is a production, like The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, that impresses the viewer with its considerable budget for sumptuous historical stylings. The Fosses’ Manhattan apartment is a jungle of houseplants and crown moldings, and Williams’s wardrobe captures Verdon’s whimsical energy: She wears crop tops, leotards, bottle green evening gowns. Both Williams and Rockwell look like they are having more fun than they are frankly used to, which puts the viewer at ease. Both of the lead actors are Oscar nominees, A-list movie stars who don’t tend to gravitate toward television projects. The first few moments of the first episode show exactly why Rockwell and Williams must have signed on for the ride; they get to tap-dance at each other, take on defunct accents, and wear a whole closet’s worth of fedoras and evening gloves. They are both having the time of their lives at a very public costume party.

But what does it all add up to? Why tell this story, and why now? It’s a question I kept turning over while watching the second episode, which flashes back to the day that Fosse and Verdon met, and unspools all the infidelities and indignities that came after, ending on the moment when Verdon decides to walk away from the marriage at last, after Fosse has cheated on her with a German translator while making Cabaret. There is something undeniably glamorous about their story—the prince and princess of American dance—and something undeniably magical in the work they crafted together. In 2019, this story should be an act of reclamation, at least for Verdon; of her agency, of her contributions, of her pain. But instead of focusing on her interiority, on developing her feelings of betrayal and resentment as more than Douglas Sirk-esque melodrama, it often shows her dancing around and on top of her emotions. In the second episode, Verdon and Fosse have a blowup on the beach; Verdon yells about the marriage, how she has put up with Fosse’s dalliances for the very last time. Something about this eleventh-hour speech rings a bit hollow, or at least unearned. Williams does the very best with the material she has, but the script should have given her—and Verdon—better.

The dancing is where the show should shine, and moments such as the “Big Spender” scene do deliver real visual pleasure. Perhaps it doesn’t need to do much more than that; some might argue that drawing attention to this era of bold choreography is reason enough to justify the show’s existence. Every physical movement in the show is purposeful and exact, just how Fosse and Verdon would have wanted it. There is not a thrust out of place. Between the verisimilitude of the movement, and the cameo appearances from a cocktail party full of historical characters (Hal Prince! Liza Minnelli! Joel Grey! Paddy Chayefsky! Chita Rivera! Jerry Orbach!), perhaps Fosse/Verdon does everything it set out to do. It’s a confection, full of spangles and name dropping and box steps.

And yet, I found myself wanting more, particularly for Verdon. Williams throws herself into the role (and finds a worthy foil in Rockwell, who manages, as his character ages, to look balding and dapper at the same time), and she milks every moment she can from the material. But we still aren’t seeing just what was happening behind the curtain. I realized that what I truly wanted to see was an entire show about Verdon: her youth on the edges of Hollywood, where her father worked as an electrician at MGM studios and her mother was a former vaudeville star. Her childhood in orthopedic boots, when her classmates called her “Gimpy” and she worried that she’d never walk normally—she started dancing as a Hail Mary effort. Her first marriage, an elopement with a journalist, and her first child, a baby she gave her parents to raise so she could move to New York and pursue her dream of dancing full-time. This entire history is only given a slight kiss in Wasson’s biography, where he pauses to describe the fifteen-year-old Verdon as having had “a killer rack.”

Those short paragraphs made me long for an entire book, just as Williams’s scenes made me yearn for Verdon’s full life story. Fosse/Verdon is a pas de deux, a story about two people colliding and combusting. Part of me wishes it was a solo.