Randolph Bourne came to hate his colleagues at The New Republic. He would later consider them toadies, more intent on sharing a drink with power than speaking truth to it. One of his most famous essays implicitly shredded Croly and Lippmann for supporting World War I: “Their thought becomes little more than a description and justification of what is going on.”

In the emerging bohemia of Greenwich Village, Bourne seemed the perfect emblem of the nonconformist. For starters, there was his appearance. An obstetrician’s forceps and a childhood case of spinal tuberculosis had turned him into a homunculus—short, bent, and ugly. Then there was his radical politics. He venerated youth culture and the young, which is why the New Left came to revere him in the sixties. Most of his essays for The New Republic were about education, a subject that consumed many of the magazine’s other thinkers, with its promise of creating a new breed of citizen. (Bourne was a devotee of John Dewey, before he angrily turned against the philosopher over his support for the war—and the philosopher turned against him, successfully insisting that Bourne be removed from the masthead of The Dial.) But when Bourne wrote about education, there was always an extra hint of rebellion, a paper airplane thrown across the room with a bomb buried in its belly.

—Franklin Foer, former TNR editor, Insurrections of the Mind: 100 Years of Politics and Culture in America

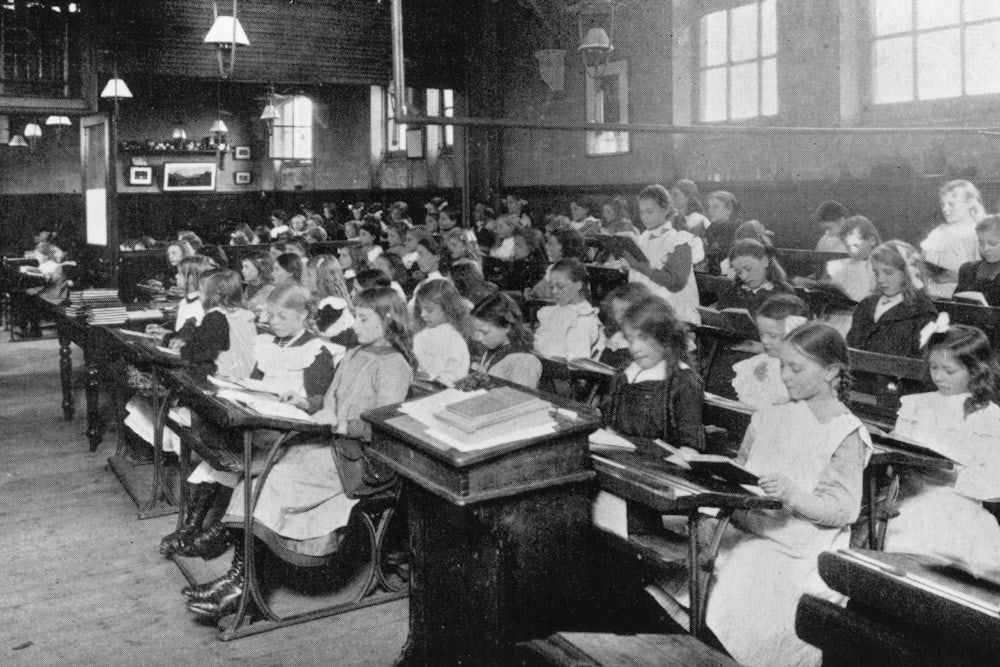

The other day I amused myself by slipping into a recitation at the suburban high school where I had once studied as a boy. The teacher let me sit, like one of the pupils, at an empty desk in the back of the room, and for an hour I had before my eyes the interesting drama of the American school as it unfolds itself day after day in how many thousands of classrooms throughout the land. I had gone primarily to study the teacher, but I soon found that the pupils, after they had forgotten my presence, demanded most of my attention.

Their attitude toward the teacher, a young man just out of college and amazingly conscientious and persevering, was that good-humored tolerance which has to take the place of enthusiastic interest in our American school. They seemed to like the teacher and recognize fully his good intentions, but their attitude was a delightful one of all making the best of a bad bargain, and co-operating loyally with him in slowly putting the hour out of its agony. This good-natured acceptance of the inevitable, this perfunctory going through by its devotees of the ritual of education, was my first striking impression, and the key to the reflections that I began to weave.

As I sank down to my seat I felt all that queer sense of depression, still familiar after ten years, that sensation, in coming into the schoolroom, of suddenly passing into a helpless, impersonal world, where expression could be achieved and curiosity asserted only in the most formal and difficult way. And the class began immediately to divide itself for me, as I looked around it, into the artificially depressed like myself, commonly called the “good” children, and the artificially stimulated, commonly known as the “bad,” and the envy and despair of every “good” child. For to these “bad” children, who are, of course, simply those with more self-assertion and initiative than the rest, all the careful network of discipline and order is simply a direct and irresistible challenge.

I remembered the fearful awe with which I used to watch the exhaustless ingenuity of the “bad” boys of my class to disrupt the peacefully dragging recitation; and behold, I found myself watching intently, along with all the children in my immediate neighborhood, the patient activity of a boy who spent his entire hour in so completely sharpening a lead-pencil that there was nothing left at the end but the lead. Now what normal boy would do so silly a thing or who would look at him in real life? But here, in this artificial atmosphere, his action had a sort of symbolic quality; it was assertion against a stupid authority, a sort of blind resistance against the attempt of the schoolroom to impersonalize him.

The most trivial incident assumed importance; the chiming of the town-clock, the passing automobile, a slip of the tongue, a passing footstep in the hall, would polarize the wandering attention of the entire class like an electric shock. Indeed, a large part of the teacher’s business seemed to be to demagnetize, by some little ingenious touch, his little flock into their original inert and static elements.

For the whole machinery of the classroom was dependent evidently upon this segregation. Here were these thirty children, all more or less acquainted, and so congenial and sympathetic that the slightest touch threw them all together into a solid mass of attention and feeling. Yet they were forced, in accordance with some principle of order, to sit at these stiff little desks, equidistantly apart, and prevented under penalty from communicating with each other. All the lines between them were supposed to be broken. Each existed for the teacher alone. In this incorrigibly social atmosphere, with all the personal influences playing around, they were supposed to be, not a network or a group, but a collection of things, in relation only with the teacher.

These children were spending the sunniest hours of their whole lives, five days a week, in preparing themselves, I assume by the acquisition of knowledge, to take their places in a modern world of industry, ideas and business. What institution, I asked myself, in this grown-up world bore resemblance to this so carefully segregated classroom? I smiled, indeed, when it occurred to me that the only possible thing I could think of was a State Legislature. Was not the teacher a sort of Speaker putting through the business of the session, enforcing a sublimated parliamentary order, forcing his members to address only the chair and avoid any but a formal recognition of their colleagues?

How amused, I thought, would Socrates have been to come upon these thousands of little training-schools for incipient legislators! He might have recognized what admirably experienced and docile Congressmen such a discipline as this would make, if there were the least chance of any of these pupils ever reaching the House, but he might have wondered what earthly connection it had with the atmosphere and business of workshop and factory and office and store and home into which all these children would so obviously be going. He might almost have convinced himself that the business of adult American life was actually run according to the rules of parliamentary order, instead of on the plane of personal intercourse, of quick interchange of ideas, the understanding and the grasping of concrete social situations.

It is the merest platitude, of course, that those people succeed who can best manipulate personal intercourse, who can best express themselves, whose minds arc most flexible and most responsive to others, and that those people would deserve to succeed in any form of society. But has there ever been devised a more ingenious enemy of personal intercourse than the modern classroom, catching, as it does, the child in his most impressionable years? The two great enemies of intercourse are bumptiousness and diffidence, and the classroom is perhaps the most successful instrument yet devised for cultivating both of them.

As I sat and watched these interesting children struggle with these enemies, I reflected that even twist the best of people, thinking cannot be done without talking. For thinking is primarily a social faculty; it requires the stimulus of other minds to excite curiosity, to arouse some emotion. Even private thinking is only a conversation with one’s self. Yet in the classroom the child is evidently expected to think without being able to talk. In such a rigid and silent atmosphere, how could any thinking be done, where there is no stimulus, no personal expression?

While these reflections were running through my head, the hour dragged to its close. As the bell rang for dismissal, a sort of thrill of rejuvenation ran through the building. The “good” children straightened up, threw off their depression and took back their self-respect, the “bad” sobered up, threw off their swollen egotism, and prepared to leave behind them their mischievousness in the room that had created it. Everything suddenly became human again. The brakes were off, and life, with all its fascinations of intrigue and amusement, was flowing once more. The schools streamed away in personal and intensely interested little groups. The real world of business and stimulations and rebounds was thick again here.

If I had been a teacher and watched my children going away, arms around each other, all aglow with talk, I should have been very wistful for the injection of a little of that animation into the dull and halting lessons of the classroom. Was I a horrible “intellectual,” to feel sorry that all this animation and verve of life should be perpetually poured out upon the ephemeral, while thinking is made as difficult as possible, and the expressive and intellectual child made to seem a sort of monstrous pariah?

Now I know all about the logic of the classroom, the economies of time, money, and management that have to be met. I recognize that in the cities the masses that come to the schools require some sort of rigid machinery for their governance. Hand-educated children have had to go the way of handmade buttons. Children have had to be massed together into a schoolroom, just as cotton looms have had to be massed together into a factory. The difficulty is that, unlike cotton looms, massed children make a social group, and that the mind and personality can only be developed by the freely inter-stimulating play of minds in a group. Is it not very curious that we spend so much time on the practice and methods of teaching, and never criticize the very framework itself? Call this thing that goes on in the modern schoolroom schooling, if you like. Only don’t call it education.