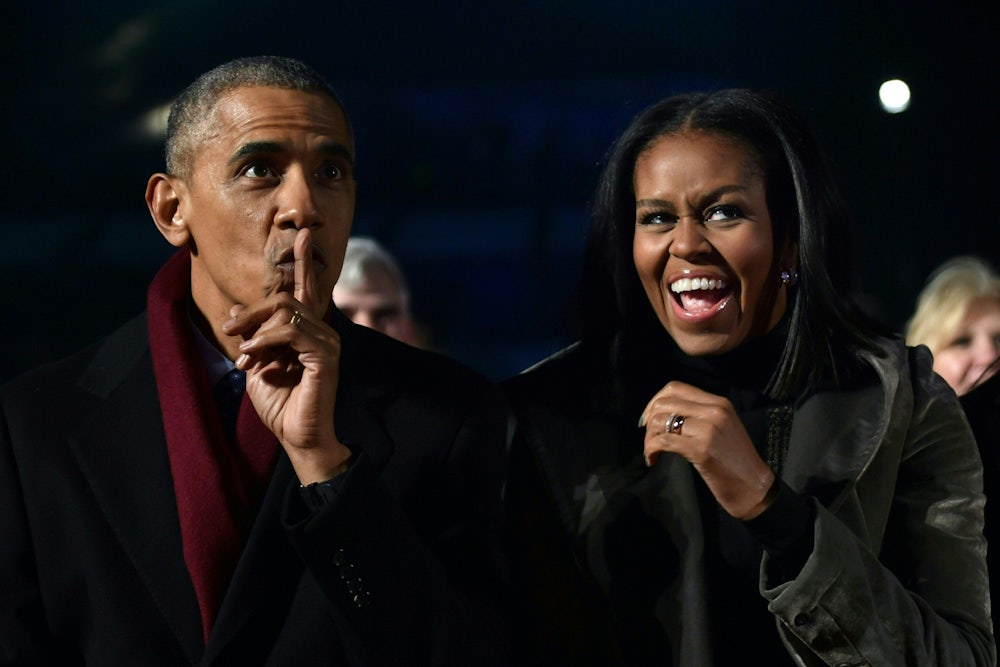

Netflix is on a buying spree. Over the last several months, the company has announced a $100 million partnership with Grey’s Anatomy creator Shonda Rhimes and a $300 million deal with TV’s man of the moment Ryan Murphy, both of which will last multiple years. Netflix has also announced a plan to flood its streaming service with content, including some 700 original projects, a staggering number for a company that has been making shows and movies for less than a decade. And on Monday, Netflix formalized a “high 8-figure deal” deal with Barack and Michelle Obama, which suggests that their TV contract will be worth a bit more than the $65 million book deal the couple signed with Penguin Random House a year ago.

The details of the Obama project are scarce, but it is nevertheless useful in parsing Netflix’s intentions. Its competitors—particularly Amazon and Disney, which is launching its streaming service in 2019—are investing in ultra-big-budget shows set in recognizable pieces of intellectual property: The Lord of the Rings in the case of the former, Marvel and Star Wars for the latter. Netflix, in contrast, is investing in the kinds of programs that you see all the time on traditional television: sitcoms, police procedurals, talk shows. It suggests that Netflix is content to replicate television as we know it—and the results are deliberately less than spectacular.

According to preliminary reporting, the Obamas will be creating programs that could include “scripted series, unscripted series, docu-series, documentaries, and features”—which is another way of saying that no one really has any idea what they’re going to be doing, including Netflix and the Obamas. With network television in disarray, Netflix is pitching itself as a safe space for creators—a place where people like Murphy and Rhimes and the Obamas can pursue projects they want to pursue, with little intervention.

This has always been central to Netflix’s mission. When it launched its first scripted series, an adaptation of the British show House of Cards, in 2011, it “offered total creative control of the production,” according to Wired, even though the show was the most expensive drama being produced at the time. This innovation doubled as a piece of branding: Many directors are wary of working with Netflix, since most marketing is done within the platform, which means that many shows struggle to find an audience; for many filmmakers, the fact that Netflix films are not widely released is considered a dealbreaker. What Netflix had to offer was creative control and deep pockets.

A New York Times report from March gave two clues about what the Obamas would do with that control:

In one possible show idea, Mr. Obama could moderate conversations on topics that dominated his presidency—health care, voting rights, immigration, foreign policy, climate change—and that have continued to divide a polarized American electorate during President Trump’s time in office. Another program could feature Mrs. Obama on topics, like nutrition, that she championed in the White House. The former president and first lady could also lend their brand—and their endorsement—to documentaries or fictional programming on Netflix that align with their beliefs and values.

Not exactly riveting programming (though, given the charisma of the Obamas, it certainly wouldn’t be unwatchable). These shows would seem to echo David Letterman’s My Next Guest Needs No Introduction, the lackluster monthly talk show for which Letterman is being paid $2 million an episode. My Next Guest doesn’t try to do much besides low-stakes conversation—the only notable moment in its short run so far has been Tina Fey calling Letterman out for not hiring enough women when he helmed The Late Show. It’s otherwise a pleasant enough hour for people who miss seeing Letterman regularly appear on television.

Disney is focusing its new streaming platform on loyalty—on attracting customers who already can’t get enough of its animated features, who obsess over the ending of Avengers: Infinity War, who watch every Star Wars spinoff multiple times. Amazon is heading in a similar direction, trying to cement Amazon Prime as a streaming king with a Game of Thrones-like, epoch-defining fantasy show that people can’t stop talking about. (Its Lord of the Rings spinoff is rumored to revolve around a young Aragorn, while CEO Jeff Bezos reportedly has high hopes for The Expanse, which Amazon is on the verge of acquiring from Syfy.)

Netflix’s strategy for maintaining its dominance in the face of this kind of competition is to cede Reddit and YouTube to its competitors. The network doesn’t seem interested in making shows that people obsess over, so much as it is in making shows that people watch after dinner. It’s a different kind of appointment television: Not programming that you anxiously wait for over the course of a week, but the kind you flick on every day.

HBO, which started the content revolution in the mid-1990s, ran away from “television” with its slogan, “It’s not TV, It’s HBO.” Amazon and Disney are following the HBO model, putting their efforts into producing programming that is decidedly not TV-ish. Netflix may be giving creative control to people like Murphy, Rhimes, and the Obamas, but it’s doing the opposite. Broadcast television might be facing existential uncertainties right now, but Netflix, armed with 125 million subscribers and an immense bank account, thinks it has figured out the easiest way to survive: Pay hundreds of millions of dollars to make the kind of TV people already watch.