I worried when I saw the trailer for The Deuce, a grimy new drama series from David Simon (The Wire, Treme, Show Me a Hero) and George Pelecanos (a veteran crime writer who worked with Simon on The Wire), that it would repeat last year’s 1970s nostalgia trip, the glossy HBO series Vinyl. Created by Martin Scorsese and Mick Jagger, Vinyl was a careening louche-fest, with record executives snorting cocaine off mirrored tables and wearing pants that lowered their sperm count. The show promised viewers a passport to a grittier (read: more authentic) time, when the city still had a “soul” and one might haphazardly wander into a Ramones show any night of the week. It thrived on the kind of unearned, glitzy danger that comes with simply evoking ’70s Manhattan.

Fortunately, The Deuce is no exercise in misplaced nostalgia. It has plenty of terror and grit, beginning with an early-morning mugging in the summer of 1971. Vincent Martino—a mustachioed bar manager played by James Franco doing his best blue-collar Brooklyn accent—is assaulted while dropping off the bar’s cash take, and pleads for his life at gunpoint before being pelted in the face and left bleeding on the sidewalk. When he staggers home, his wife (a bouffanted Zoe Kazan) is nowhere to be found. She has gone out boozing, leaving their kids with her mother. Later that morning, as Vince smokes a predawn cigarette as he starts his Manhattan shift, he crosses paths with Darlene (Dominique Fishback), a baby-faced prostitute from the sticks of North Carolina. They exchange the kind of glance that can only be shared by two people who understand each other’s misery. Both are living out their own “summers of hell.”

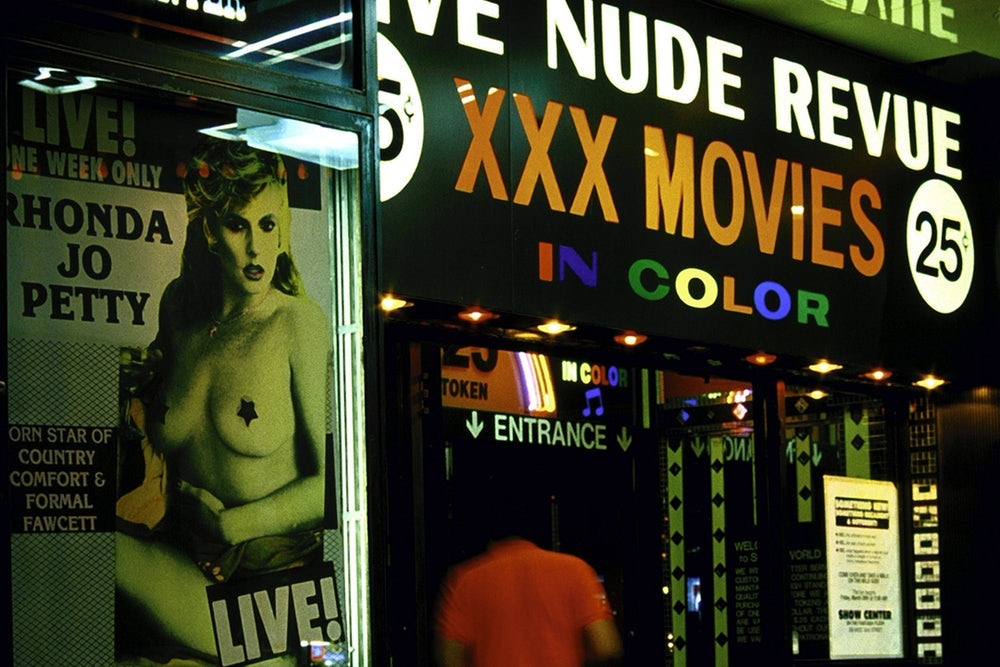

The Times Square of The Deuce is not just infernal but well on its way to collapse. The show gets its title from the ’70s-era nickname for the mangy strip of 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues, which was then depravity central. City services were tapped dry; sewage workers went on strike; and the part of town that’s now home to M&M’s World and The Lion King was overrun with smutty movie theaters, massage parlors, and X-rated bookshops, many of which were often raided by the police. That summer, according to The New York Times, the cops hit eight sex shows in one night, arresting 20 people. Mayor John Lindsay declared a crackdown on prostitution in Midtown that was focused on curbing the supply rather than eliminating the demand. “There are maybe 3,000 of us in the city,” one sex worker told the Times in 1971, “and if we each have ten customers a day that’s 30,000 men who paid out.”

Her turf is the world portrayed in The Deuce. The show attempts to capture what happened at a very particular neon intersection of vice and suffering and capitalistic hustles. The series covers a decade of change. Just when Gerald Ford was telling New York to drop dead and the Bronx was burning to the ground, new enterprises began to prosper. The pornography industry defeated regulations and became big business—by the end of The Deuce’s first season, Deep Throat has hit movie theaters—and Times Square nightlife ventures (from peep booths to rock clubs), many underpinned by crime syndicate investments, are cutting deals with the cops and raking in cash.

As in The Wire, all the dirty money is inevitably accompanied by violence, blight, and a pervasive sense of hopelessness. In a scene halfway through the season, two prostitutes stand outside a sleazy Chinese restaurant as it rains. A young newcomer named Lori (a smart-alecky Emily Meade, who delivers impeccable eyebrow-acting all season) grumbles about the downpour. Eileen (Maggie Gyllenhaal), who goes by the street name Candy, is a veteran sex worker who wears a curly blond Orphan Annie wig and a perpetual sigh. (Gyllenhaal also serves as a producer of The Deuce, a role she asked for as a condition to playing Candy, she says, because she “wanted some kind of guarantee that they wanted not just my body but also my mind.”) A daisy-duked Fantine in platform sandals, Eileen works to support a child in the suburbs. When Lori suggests not turning tricks because of the bad weather, Eileen snorts at the thought. She has been around long enough to know that you can’t take a rain check on survival.

Lori, Darlene, and other women who work with pimps often suffer violent, horrifying punishment if they do not perform—one aspect of The Deuce that is brutal and hard to watch. Eileen, who has “no man,” works as her own boss. She won’t suffer the same repercussions if she takes the night off, but she also knows she can’t afford to skip work. She heads to the skin flicks, where a man asks her if she likes movies and immediately unzips his pants in the flea-ridden, red velvet seats. As Eileen gets to work, a giant rat crawls from the floor up to her wig. It is horrifying, humiliating, and a moment of stark clarity; her sorrow is complete.

In Eileen’s case, it isn’t the work that debases her. It’s her lack of control over her life, her alienation, the violence she suffers alone in hotel rooms at the hands of johns who don’t want to pay. She finds respite and agency in the world of filmed pornography, where she discovers that she can make money with a lot less risk. In the second episode, Eileen fills in at a porn shoot in the Bronx, and as she has cold potato soup splashed over her face, you see a twinkle in her eye. In this work, she can use her entrepreneurial spirit to her advantage. She is present at the birth of something.

James Franco plays not only Vince Martino in The Deuce, but also his twin brother, Frankie. If Vince is virtuous, then Frankie, with his gambling debts and libertine reputation, is a bastion of vice. Franco’s weaselly smarm works perfectly as rat fink Frankie, and he brings a smear of buttery tenderness to Vince, who opens a seedy new bar near Times Square called the Hi-Hat, which welcomes prostitutes. When I heard about Franco’s acting stunt, I was skeptical: The duplication trick could easily have become the focus of the show, as the brothers attempt to become smut impresarios with the help of a rotund, industrious mob boss named Rudy Pipilo (Michael Rispoli). In the wrong hands, The Deuce had the potential to turn into a show about the ’70s that focused exclusively on a kind of bygone machismo, a wish fulfillment for Taxi Driver fans who still quote Travis Bickle’s “You talkin’ to me?” when they look in the mirror.

Simon and Pelecanos, however, allow a multitude of characters to share the spotlight. (They also brought in several women to work on the project, including director Michelle MacLaren and crime novelists Megan Abbott and Lisa Lutz in the writers’ room.) The misery is spread around evenly, which feels like a more accurate evocation of ’70s Manhattan than a rhapsodic love letter to the city’s one-time rough edges. We learn the backstory of Darlene, who returns to North Carolina only to lie to her former friends that she is a model in New York; in the process, she dupes a young waitress into coming north on the bus to join the trade. We meet Ruby, an astringent prostitute who is known on the street as “Thunder Thighs” and becomes the tragic clown of the season as she attempts to laugh through her pain. The coterie of pimps who all meet up at Leon’s Diner to eat greasy bacon and talk shop are portrayed as tough, sexist, flamboyant braggarts—but also as unhappy cowards trapped in a system from which they find little respite and no escape.

Gbenga Akinnagbe, an alumnus of The Wire, plays Larry Brown, a slick dresser who constantly holds the threat of physical violence over Darlene; there is no romanticizing his role in her terror, even as Akinnagbe brings an undercurrent of grief to his verbal lashings. As in The Wire, the bleakness of The Deuce is individual, interpersonal, and institutional all at once. The lubricity of Times Square could not have flourished without corrupt (or absent) police, and a great deal of The Deuce is dedicated to showing the many ways in which the NYPD made deals or turned a blind eye to the goings-on. Lawrence Gilliard Jr. is moving as Chris Alston, a cop who finds himself disturbed by the ethical ellipses of working on 42nd Street, and decides to help a gumshoe reporter named Sandra Washington (a splendid Natalie Paul) publish an exposé. Another officer nicknames her “Angela Davis” when she tries to go undercover as a prostitute for a night. Her shoes give her away, Alston says: Street workers don’t wear Bonwit Teller. Washington herself comes up against city crookedness as the NYPD attempts to thwart her exposé.

David Simon has always been a kind of soothsayer of interconnected graft: The police are dirty, the journalists are compromised, the slime begins at home. And, yet, radiant personal stories shine through the muck. No one on The Deuce is having much fun. The sex isn’t prurient, but it isn’t always joyless. The clothes are mostly shabby, the porn shoots are low-budget, the bars are raucous only when a glam band rolls through. But importantly, everyone remains stuck on the same block, living shoulder to shoulder, forced to confront one another. The Deuce is about intractability and cycles; the vortex of poverty and pain that characterized the city in the bankrupt era. Some people manage to get out with plucky innovation; some never will.

Perhaps there is a tacit nostalgia play in this; perhaps today’s New Yorkers dripping with sweat on wi-fi-enabled subway platforms will long for the crackling, seamy city of 40 years ago. But I doubt it. If nothing else, The Deuce shows the ’70s as a hell that no one should want to return to, even if it was a hotbed of creativity. As one aging prostitute puts it on the show: “Daddies, husbands, and pimps, they’re all the same. They love you for who you are, until you try to be someone else. At least pimps are up front about it.” Cities are always changing, and New Yorkers have maybe never loved Times Square. The Deuce is just up front about it.