One day, while driving home to Berkeley after a poorly attended reading in Marin County, Ayelet Waldman found herself weighing the option of pulling the steering wheel hard to the right and plunging off the Richmond Bridge. “The thought was more than idle, less than concrete,” she recalls, “and though I managed to make it across safely, I was so shaken by the experience that I called a psychiatrist.” The doctor diagnosed her with a form of bipolar disorder, and Waldman began a fraught, seven-year journey to alter her mood through prescription drugs, a list so long that she was “able to recite symptoms and side effects for anything … shrinks might prescribe, like the soothing voice-over at the end of a drug commercial.” She was on a search for something, anything, that would quiet the voices, the maniac creativity, the irritable moods that caused her to melt down over the smallest mistakes. That’s when she began taking LSD.

Lysergic acid diethylamide is in the midst of a renaissance of sorts, a nonprescription throwback for an overmedicated generation. As pot goes mainstream—the natural solution to a variety of ills—LSD is close behind, in popularity if not legality. By 1970, two years after possession of LSD became illegal, an estimated two million Americans had used the drug; by 2015, more than 25 million had. In A Really Good Day: How Microdosing Made a Mega Difference in My Mood, My Marriage, and My Life, Waldman explores her own experience of taking teeny, “subtherapeutic” doses of the drug. This “microdose,” about a tenth of your typical trip-inducing tab, is “low enough to elicit no adverse side effects, yet high enough for a measurable cellular response.” Her book is both a diatribe and diary. She offers a polemic on a racist War on Drugs that allows her, a middle-class white woman, to use illegal substances with ease, as well as a daily record of the improved mood and increased focus she experiences each time she takes two drops of acid under the tongue. Microdosing advocates argue that LSD is a safer and more reliable alternative to many prescription drugs, particularly those intended to treat mood disorders, depression, anxiety, and ADHD. Respite is what Waldman is chasing, a gradual tempering, drop by drop, of our fractured, frazzled selves. If the 1960s were about touching the void, microdosing is about pulling back from it.

I’d been on prescription antidepressants for about a year when I opened Waldman’s book. To say that mental illness runs in my own family would be an understatement. After listening to a very abridged version of my family medical history, my psychiatrist called me the “poster child for mental health screenings before marriage.” My sister, gripped with undiagnosed postpartum psychosis, once fantasized, as Waldman did, about driving off a bridge with her infant daughter in the car, and my mother killed herself by overdosing on OxyContin and other legal drugs a month before I graduated from college. Battle is the stock verb of illness—we battle cancer, depression, and addiction. But I cannot in good conscience say I battle my depression and anxiety. Rather, my madness and I are conjoined twins, fused at the head and hip: Together always, we lurch along in an adequate, improvised shuffle.

Like Waldman, I worry about the negative effects of taking an SSRI long-term. The daughter of hippies, a flower grandchild, I don’t trust the pharmaceutical industry to prioritize my wellness over their profits. I’ve long agreed with Waldman that “practitioners, even the best ones, still lack a complete understanding of the complexity and nuance both of the many psychological mood disorders and of the many pharmaceuticals available to treat them.” So when I finished the prologue to A Really Good Day, I set the book down and left my therapist a voicemail announcing my plan to wean myself off Celexa. Then I went on reading. I did not mention the new-old mystic’s medicine beckoning me—the third eye, the open door.

It’s surprisingly simple to get LSD. I asked a few friends, who asked a few of their friends, and the envelope arrived just a few days later with a friendly, letter-pressed postcard. Spliced into the card, via some impressive amateur surgery, was a tiny blue plastic envelope. Inside that was a piece of plain white paper divided with black lines into ten perfect squares: ten tabs of acid, 100 microdoses at a dollar each.

LSD has been illegal in the state of California since 1966, six months after LIFE magazine published a scare piece about “the exploding threat of the mind drug that got out of control.” At its invention, LSD was highly controlled—first synthesized in 1938 by Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann, an employee of what is now Novartis, one of the world’s largest multinational pharmaceutical companies. Hofmann was attempting to isolate and replicate a profitable analeptic based on compounds that naturally occur in ergot, a fungus. He did not discover LSD’s psychoactive properties until five years later, when he ran a self-experiment in which he took 250 micrograms of acid—25 times the amount Waldman takes every few days—went for a bike ride, and thought he was dying.

“My surroundings had now transformed themselves in more terrifying ways,” Hofmann recounted. “The lady next door, whom I scarcely recognized, brought me milk—in the course of the evening I drank more than two liters. She was no longer Mrs. R, but rather a malevolent, insidious witch with a colored mask.”

By midcentury, LSD had made its way to American hospitals, where researchers intended to use it to induce and study psychosis. Inconveniently, doctors and staff observed that the drug meant to make people insane was more likely to induce in patients a sense of well-being, or even euphoria. The transition of LSD from lab to therapist’s couch was spurred by Dr. Sidney Cohen, who administered LSD to himself and other “normal people” at the Veterans Administration in Los Angeles. In 1956, Cohen filmed a housewife before she took LSD: She sits in her good dress with good posture and a perfect manicure, visibly pleased when Cohen informs her that she is a “very stable and well-balanced person” according to a “series of psychological tests.” Then she drinks a glass of water laced with LSD. Soon the drug kicks in, and her movements grow playful and sensual. “It’s like you’re released, or you’re free,” she says, her face turned heavenward. “Everything is one. You have nothing to do with it. I am one with what I am.” When was the last time you felt at one with what you are?

Researchers suspected that LSD could facilitate creativity, cure alcoholism, and cheer sullen grad students. But in 1962, The FDA tightened regulations on the approval of new drugs, which restricted the legal supply of LSD. The result was a black market rife with unregulated doses, experimentation, and contamination. During the “Pink Wedge Incident” of 1967, a shipment of LSD laced with another psychotropic drug caused a rash of panic attacks in Haight-Ashbury.

If cocaine kept Wall Street humming at all hours in the 1980s, LSD today keeps the ideas flowing in Silicon Valley’s creative economy, solving problems that require both concentration and connectedness. Microdosing is offered as an improvement over Adderall and Ritalin, the analog ancestors of modern-day smart drugs. Old-school ADHD methamphetamines, it would seem, clang unpleasantly against Silicon Valley’s namaste vibe. Today’s microdosers “are not looking to have a trip with their friends out in nature,” an anonymous doser recently explained to Wired. “They are looking at it as a tool.” One software developer speaks of microdosing as though it were a widget one might download for “optimizing mental activities.” The cynic’s working definition might read, “microdose (noun): the practice of ingesting a small dose of a once-countercultural drug that made everyone from Nixon to Joan Didion flinch in order to make worker bees more productive; Timothy Leary’s worst nightmare; a late-capitalist miracle.”

Productivity is not Waldman’s purpose—pre-LSD, she could write a book in a matter of weeks—but neither is non-productivity, the glazed-over stoner effect. Waldman is instead insistent on the therapeutic value of microdosing. There is nothing, it seems, that LSD isn’t good for, no worry it can’t soothe, no problem it can’t solve. Once an afternoon delight of recreational trippers and high-school seniors, LSD has become a drug of power users: engineers, salesmen, computer scientists, entrepreneurs, writers, the anxious, the depressed. The trip isn’t the thing; instead, microdosing helps maintain a fragmented, frenzied order, little by little, one day at a time.

Waldman is good company; she is candid, goofy, and beyond knowledgeable about the drugs she takes to stabilize her mood, and the risks she takes in procuring them. Her expertise on the subject is twofold: She is a former federal public defender and a law school professor who taught a seminar on the War on Drugs at the University of California at Berkeley.

Waldman goes to great length to establish her averageness. She has “never been what you would call a regular drug user,” never bought illegal drugs from a dealer, barely even drinks. Sure, she’s done some drugs—“more than some people my age, less than Presidents Obama and Bush”—but Waldman is at pains to present herself as “the mom surreptitiously checking her phone at Back to School Night, the woman standing behind you in Starbucks ordering the skinny vanilla latte.” She rhetorically aligns herself with women who are, as her kids would say “totally basic,” while exposing a slightly condescending and very white notion of who those women are. By the book’s end, however, these apparently unintended missteps turn out to be a conscious strategy deployed for a higher purpose. Come for mom’s mental health memoir, stay for the careful and convincing polemic against the War on Drugs.

I graduated from high school in 2002, when LSD use among 18-year-olds was on the decline after hitting an all-time high in 1996. I remember learning the origins of the drug in middle school, where I was named “Outstanding D.A.R.E Student of the Year,” an honor that came with a brand-new satin jacket emblazoned with the D.A.R.E logo. The story we were told went something like this: LSD is a dangerous chemical developed by the U.S. military as a weapon of psychological warfare. The army had indeed conducted experiments with LSD on its soldiers in the 1950s through the 1970s, as had the CIA. But psychosis, it turned out, was not the best instrument of war. Patients dosed with LSD would laugh and cry, and reported seeing and hearing things. Old stigmas die hard: Today, D.A.R.E still lists LSD as a “potent hallucinogen that has a high potential for abuse and currently has no accepted medical use in treatment in the United States.”

Waldman vanquishes many of D.A.R.E’s “just say no” boogeymen, among them meth mouth, acid flashbacks, and the loss of spinal fluid allegedly caused by MDMA, which Waldman and her husband use to supplement their conventional couples therapy. Eventually, Waldman’s honest and intelligent ethos takes the form of a humane, well-reasoned, and absolutely necessary argument for a major overhaul of America’s drug policy. The book triumphantly coheres in a lucid manifesto of how and why the racist, immoral undertaking called the War on Drugs has failed.

Drug criminalization has long been an effective tool of marginalization in America. John Hudak’s Marijuana: A Short History explains how the use of the word “marijuana” was itself a propaganda tool advanced by fearmongers to “vilify” Mexicans and Mexican-Americans after the Spanish-American War, so much so that some cannabis reformers still refuse to use the word. But of all the lies Mr. and Mrs. Reagan told me, the one I was most gratified and embarrassed to have Waldman demolish is the long-held assertion that most recreational drug users in America are black. White people, in fact, do more drugs than black people, and this is true using a variety of metrics. That I needed, at least on some level, this fact-based corrective has everything to do with my own whiteness, which still falls prey to myths about black people that are left unchecked by my everyday, white experiences.

Waldman adds her voice to those of doctors, therapists, and researchers in opposition to scientific censorship and in support of “a world free of a drug market controlled by vicious criminal syndicates, where hundreds of thousands are murdered and hundreds of thousands more die of drug reactions and overdose, where millions are incarcerated, and where none can gain legal access to drugs that have the potential for markedly improving their lives.” She has a convert in me. Yet I found her book at times too careful. Her lawyerly argument refines rather than resists the binary between medicinal and recreational drugs, a rigid distinction long held by squares and used in some states to craft legislation decriminalizing medical marijuana, thereby preempting all-out legalization. Waldman includes powerful anecdotes of the injustices visited by federal drug policy upon her former clients, typically people of color. But what really stings is her decision to aim her book at affluent moms. A Really Good Day is a passionate, persuasive argument for drug decriminalization disguised as an accessible memoir about one mother’s zany LSD experiment.

I consider my own zany experiment. I’ve flipped over the postcard every few days, checking to see that the LSD blotter paper is still there. The truth is, I haven’t yet found the time to switch to another alteration in mood. Instead, as I transition from my antidepressant, I reach for a more available form of microdosing: marijuana. Like LSD, marijuana has what Waldman calls “a very low toxicity level and a large safety range.” It also enables me to read and write again after a long, melancholy drought.

If being a woman is crazy-making, Waldman argues, being a woman who makes art is a kind of schizophrenia. “Though I am proud of my books, there is a vicious voice in my head that tells me I’m worthless,” she writes. “Every single time I sit down to work, I hear that ugly whisper in my ear.” I suspect most female artists have at least two voices in their head: one voice saying we’re either property or prey, and another voice, perhaps our own, which says only one word, one syllable, but says it again and again and again, a relentless chugging: make, make, make, make.

As a diary, A Really Good Day is unabashedly indebted to Virginia Woolf. Waldman searches for a room of her own throughout, tired of squatting in her husband’s studio, longing for an office of her own where she can paint the dark walls white, where she can calm her voices of creative doubt. Waldman’s fears of a bad trip—“The prospect of being locked in my own ugly mind terrifies me”—echo those of the unnamed narrator in “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s late-nineteenth-century short story of a woman whose postpartum bed rest becomes a prison of paternalism and insanity. (Her plight, “hysterical neurosis,” was in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 1980.)

Together, these mixed messages give female artists an ironic advantage: We are constantly asked to see the world through another’s gaze. But what if our art-making makes us mad? Waldman looks back on a time when she wrote three novels in six months with concern rather than pride: “This type of sublime creative energy is characteristic of the elevated and productive mood state known as hypomania.” There are many words she doesn’t use to describe her tremendous creativity, among them inspiration and genius. Waldman emphasizes—and overemphasizes—that every drug she takes has a therapeutic purpose. If a person uses drugs to relieve physical or psychological pain, to alleviate a frozen shoulder, nausea from chemo, or anxiety, isn’t she doing so in order to be happy?

A Really Good Day’s focus on the cessation of pain reads like hard-learned rhetorical savvy from a writer who knows all too well how society trains women, especially mothers, to turn on each other. Waldman lived through a public shaming before outrage theater was the admitted business model of the internet: In 2005, she published an essay in The New York Times declaring her supreme love for her husband over their four children, earning her the ire of haters everywhere. Waldman has plenty of pain—pain that microdosing LSD undeniably soothes—but what about pleasure? Can’t mothers also enjoy drugs? And what if those of us who already do could admit to it without apology?

A friend I’ll call K, a writer and a publicist at an independent press, came for a visit recently. Our husbands were away, working, and they had left us to parent solo for the weekend. Instead, K came over so we could pool our mothering resources. On Saturday, the children woke us at 6 a.m., and we struggled to feed them breakfast. By 7 a.m., K and I each popped a marijuana edible from my stash. It was going to be a very good day, damn it.

K and I were not microdosing for a sub-perceptual experience. We wanted to have fun and be good moms while having that fun. We are both regular recreational drug users with enlightened husbands and drug-friendly families. My mother often spoke of smoking pot and taking LSD while pregnant with me—they helped her quit smoking and drinking—and K had recently discovered a poem written by her mother when K and her two sisters were very young, an ode to “grass in the box / bread in the oven.” Wake and bake was practically our birthright.

Art-making, drug-enjoying mothers are our matrilineage, yet K and I hardly ever see this part of ourselves reflected in the broader culture. If there’s anyone we identify with, it would be Broad City’s Abbi and Ilana, despite their ecstatic childlessness. It’s more likely for a pregnant woman or a mother to be invited to pass the dutch at a party than on TV. Everyone in pop culture gets to blaze with impunity, it would seem, except mothers. Call it the grass ceiling.

“It’s a tricky thing, acid,” a guy called Max tells a young Joan Didion in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, her chronicle of a summer in the Haight. “When a chick takes acid, it’s all right if she’s alone, but when she’s living with somebody this edginess comes out.” Max doesn’t wonder what it does to a woman to flee her parents’ home as a teenager in 1967 and hitch to San Francisco and arrive at the so-called revolution, only to find herself responsible for the cooking, the cleaning, the child-rearing. He’s not what you would call enlightened, that Max. Yet I think he’s onto something. I remember Dr. Cohen’s experiments on that “normal” woman, filmed almost like a freak show: This drug is so powerful it can ignite even the imagination of a dunderheaded housewife.

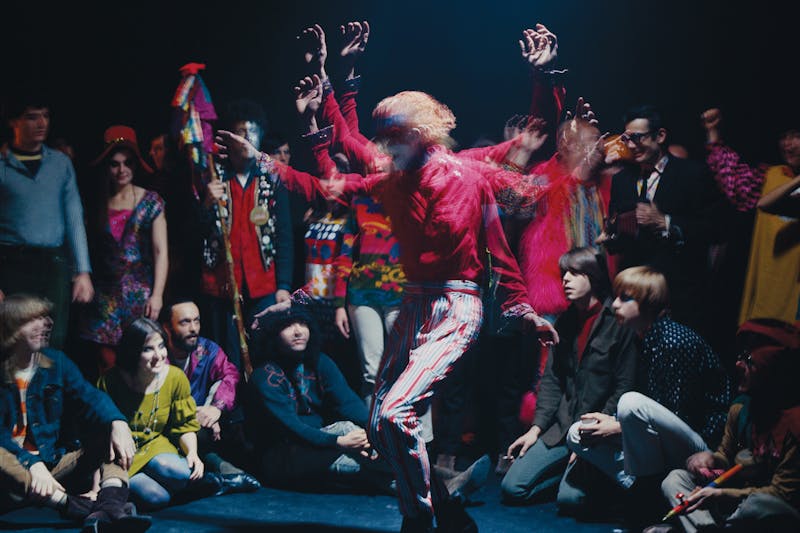

Didion offered “society’s atomization” as an explanation for Haight-Ashbury, and the timely image stuck. Ours too is a fractured time, perhaps even a shattered time, a time of forever war with a rising generation of young people poised to inherit a ruined planet and forced to divest from the values that have left them worse off than their parents: consumption, inequality, selfishness, and greed. Perhaps this is the occasion for the reemergence of mind-altering drugs in an unexpected societal strata. Illegal and semilegal drugs promise all sorts of salve: spiritual, artistic, a surrendered peace between our bifurcated, hysterical selves, maybe even the psychic melding of our fractious existence into something whole, something healed, something beautifully beyond words.

The dying have already begun to microdose. Doctors are starting to use LSD and psilocybin mushrooms in palliative care—a category of caretaking that should include most women, most artists, and all parents of small children. How about recreational weed and ’shrooms for all adults, and a prescription for LSD for every new mother? Put it in the cucumber water at yoga, the cold-pressed watermelon juice at the farmers market. Drop a tab into our epidurals. We could—and Waldman would say should—work toward making this world a little less escape-worthy.

I am writing this a little high, my daughter napping across the hall of our house with all its original woodwork. My sister did not drive off a bridge. She suffered two years of severe postpartum depression and a divorce rather than take prescription antidepressants, which were very risky for someone with her history, yet her only legal option for help. She is thriving now, but she was in such pain for so long.

She’d seen our mother yanked by widowhood, poverty, and the mysteries of her chemical brain into a depression that SSRIs couldn’t touch. She’d seen our mother prescribed legal heroin for pain associated with Lyme disease—saw, as I did, the pills not yet dissolved on her tongue when she would overdose, which was often. What if my sister had been offered microdosing? What if our mother had?

It’s been two weeks since I called my therapist. I’m entirely off my antidepressants, smoking lots of weed, and more curious than ever about the promises of LSD. I imagine Joan Didion reporting from the Haight in 2017, using her iPhone to record interviews, checking Reddit to see what molly is, texting her friends back in Berkeley to let them know she’s safe, seeing which of these hang-up-free fellows are on Tinder. In 1967, Didion’s shattered society had distinct edges, often sharp ones. Today, those previously discrete pieces of experience—the local, the global, the personal, the political—are often indistinguishable. News and entertainment merge into infotainment. On college campuses, free speech and trigger warnings intertwine beyond recognition. Corporations are people; the current political scene is a long, painful flashback. In the anemic blue light of the internet, these heated spheres glob together like the contents of a lava lamp, swirling and surging with humor and fear, interconnectedness as both philosophy and aesthetic. Our feed, we call it—a sustaining, scrolling blur of information and misinformation, personalized, of indecipherable autonomy, at once alienating and the source of our collective identity, such as it is. I watch myself transmogrified by media, itself made by and for people and bots, and I watch it warp others. How many times a day do I find myself thinking: Is this real? Or, colloquially: Am I tripping?

Being alive and paying attention in this moment is often hallucinatory. I’ve heard people say that nothing makes sense of the senseless like LSD. I, for one, sure could use a sense of oneness, of unity and contentment, some way to accept and forgive and love this entire fucked, fracked, and fractured universe. I keep my postcard of LSD in a recipe box on a high shelf in my kitchen. The promise of oneness beckons, and I’ll soon abide.