The last we saw of President George W. Bush in Africa, he was literally dancing into the sunset of his presidency, on this occasion with President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf in Monrovia, Liberia, America’s only former colony on the continent. There was much to celebrate. Despite the fact that his legacy was already being defined by a disastrous war in the Middle East and economic crisis at home, Bush has since been recognized by fans and critics alike to have done the most of any American president for the African continent since perhaps John F. Kennedy in the late 1960s. Bush’s President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), his signature Africa initiative, has been credited with saving millions of lives on the continent. Despite backlash about the program’s moralistic focus on abstinence, it was an unprecedented success.

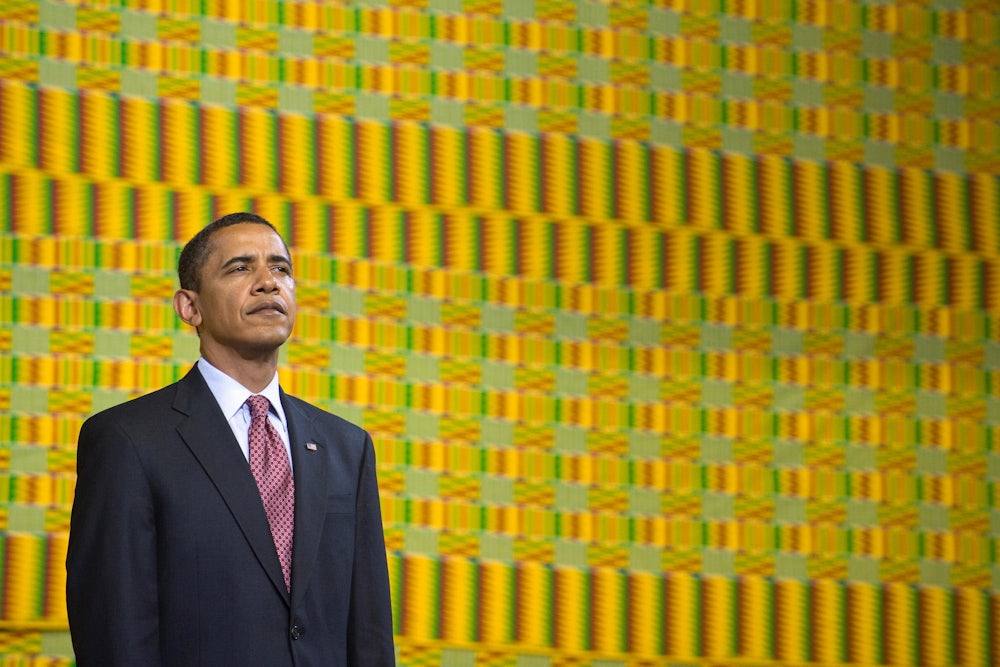

Bush’s successor arrived in Accra, Ghana, in 2009 with a different message. Barack Obama, the first American president with African ancestry, visited the famous “door of no return” through which slaves were led out to waiting ships at the Cape Coast Castle. He addressed the Ghanaian parliament, declaring that “the 21st century will be shaped by what happens not just in Rome, or Moscow or Washington, but by what happens in Accra as well.” He added, “Africa’s future is up to Africans.”

Obama’s popularity surged with Africans. All over the continent there are residential areas, roads, even barber shops named after the president. Harvard economist Grieve Chelwa recalls the excitement that greeted an American president who had “clearly identifiable roots, within this century,” to the continent. On the day of Obama’s inauguration, a cab driver in Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, told Grieve, “Since a black man is the president of U.S., things are finally going to change for us black people.”

The general sentiment was that Obama, whose grandfather was a cook for the British in Kenya, would have a personal investment in Africa. He would be motivated by a genuine desire to empower citizens of the continent; a shift from the missionary quality that characterized Bush and his predecessors in their engagement toward Africa—a modern-day rendition of Kipling’s white man’s burden.

Nearly eight years later, there is a palpable sense that Obama’s legacy in Africa is not what it could have been. It is not only that his administration has failed to produce a single policy that could rival the success of PEPFAR; it has actually cut funding for the program, leading critics to warn that Obama may have set back progress on AIDS by years. Power Africa, Obama’s initiative to light up the continent with more than 30,000 megawatts of power, has only generated a little over 4,000 megawatts. The premier U.S.-Africa trade agreement, the African Growth and Opportunity Act, was renewed by Congress last year, but U.S. trade with Africa still heavily leans on extractive economies where natural resources are a source of conflict. The fraught governing coalition in Africa’s newest country, South Sudan, shepherded into the international community by the U.S., has fallen apart.

Still, the Obama administration has laid the groundwork for stronger ties between the United States and Africa in ways that often don’t make headlines. In his Accra speech, he made a direct pitch to Africa’s youth, saying “it will be the young people” who bring about change. It was a salient point, given that approximately 60 percent of the continent’s total population is below the age of 35. And true to his word, it has been the president’s Young African Leadership Initiative (YALI), a small and often overlooked program, that experts predict will have the longest impact by establishing a new American engagement with the continent’s youth.

A common criticism of Obama is that he left the business of development in Africa late in his administration. The first Young African Leaders Forum was not held until 2011. The current iteration of YALI, and the more high-profile Power Africa initiative, didn’t begin until 2013, while the first U.S. Africa Business Conference didn’t take place until the following year.

But Melvin Foote of Constituency for Africa (CFA), which for decades has lobbied on the Hill for African development issues, acknowledges the tremendous difficulties Obama faced in his first few years in office. He “had to be America’s president first, before he could be the rest of the world’s president,” Foote says. In the midst of the Great Recession, facing an obstinate Republican opposition in Congress, there was little enough support for a stimulus plan, let alone new aid projects for Africa. During a briefing early in Obama’s administration, the CFA proposed a program like YALI that would have a big impact but cost very little.

This year, the Mandela Washington Fellowship—the main program of YALI—brought 1,000 African professionals between the ages of 25 and 35 for its six-week professional development program. The participants spend a total of 44 days at academic institutions all across the country, ranging from Florida International University to the University of Wisconsin. Twenty-five students are placed at each academic institution based on their training track: Business and Entrepreneurship, Civic Leadership, or Public Management (expanded to include an Energy Policy specialization). The academic component is followed by a summit in Washington, D.C., where fellows get to meet with leaders from public, private, and nonprofit sectors.

It may sound like a glorified student exchange program, but such programs have had a long and influential history. For Omolade Adunbi, a professor of African Studies at the University of Michigan, the YALI fellows follow the lineage of African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah and Nnamdi Azikiwe, who studied in the U.S. in the 1930s before going back to lead the independence movements in Ghana and Nigeria, respectively. If they are not returning to their homes with revolutionary fervor, they are bringing back skills and knowledge that could be used to address the acute problems of 21st-century Africa, such as developing sustainable agriculture. “They could learn mechanized farming from somewhere like Iowa for instance,” Adunbi says, and “reshape the discussions about the future of the continent.”

After the main program, 100 fellows are selected to stay and complete a six-week course in which they are placed with companies or government agencies—such as Coca Cola, the city of Philadelphia, or the Youth Sentencing & Reentry Project—that relate to their professional interests or goals. Teodosia Monica Bivini, an educator from Equatorial Guinea, was placed at South Shore Elementary School in Seattle, where she gained exposure to the kind of administration necessary to run an early childhood education program. Peter Nawa, a publisher in his native Zambia, was placed at Boston’s Cambridge College, where he learned about product development, crowdsourcing, and social media. Yves Tuyishime, an energy specialist from Rwanda, was stationed at the University of California, Davis, where he got to visit the California Energy Commission, Berkeley Lab, and Power Hive—a renewable energy company that Tuyishime had encountered when it was considering setting up shop back in Kigali.

A great deal can come out of these humble professional beginnings. Fellows who complete a leadership development plan are eligible for seed funding for their projects, plus they have the connections they established in the U.S. Having spent six weeks in America, the fellows are connected to an existing network of 200,000 people who have already gone through the program. Last May, the first regional conference of alumni and fellows was held in Johannesburg, South Africa. But they mostly keep in touch through the YALI portal online and through social networks such as Facebook and WhatsApp. The seeds have been sown for a new generation of leaders on the continent who only benefit from being familiar with one another. As Cyrus Kawalya, a professional photographer who went through the program, said on the YALI Voices Podcast, “It’s going to be like five years down the road when some of us become president, some of us become ministers, and we already have this beautiful relationship we’ve created amongst us? It’ll be easy for us to agree on so many things, which probably the older generation can’t do that.”

Furthermore, they will have a lifelong connection to the United States. Lina Benabdallah, a Phd candidate in African studies at the University of Florida, says YALI is commendable not only for its focus on business and development, but because it shows that the U.S. views the program as being in its own national interest. “Africans are being invited to Chinese Universities. China is offering scholarships,” she explains, “so that when Africans are thinking about technology, skills, they are thinking of China as a valid option. They get to discover China, they get to see the success of the development model, they get to be impressed and influenced positively.”

She adds, “It is very smart and useful in focusing on management, and provides ‘soft-power opportunities’ for the Africans to feel that they can access opportunities in the U.S.”

This gets to one of the flaws in the YALI model. Whereas YALI is largely targeting young entrepreneurs, China is targeting politicians. “When whole bunches of African leaders have been trained in China, they are more likely to be receptive to Chinese policies,” Benabdallah says. Zachariah Mampilly, a professor at Vassar College and co-author of Africa Uprising: Popular Protest and Political Change, agrees. He notes that the U.S. is passing up the opportunity to inculcate a stronger commitment to upholding democratic ideals. Mampilly says the focus on training people to fix problems with social and economic entrepreneurship, rather than engaging in the political processes in their own country, is a fundamental weakness of the program. “The people selected seem to be very nice, very impressive, but the reason they are selected has very little to do with the actual social, political, and economic concerns of their country,” Mampilly says. “If you can build a windmill that can generate electricity for your little light bulb in your hut, that will get you selected to YALI. It has nothing to do with the actual power infrastructure of the country. It actually speaks to an absolution of the country providing electricity.”

Mampilly, who documents the upsurge in youth activism in his most recent book, points out that “young Africans are more engaged in their politics right now than probably since the anti-colonial struggles in the 1950s, and maybe the 1990s pro-democracy movement.” He cites the examples of young leaders of social movements in Sudan, Angola, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe. Last year, it was revealed that the activists Y’en a Marre of Senegal and Balai Citoyen of Burkina Faso had travelled 6,000 miles to the Congo to train and share strategies with young Congolese activists. “Imagine bringing these people here,” Mampilly says, “and with the seal of approval of the U.S. government, to interact with each other and share ideas and organizing strategies. ... If there is sincerity in engaging the youth bulge a political initiative towards African youth would be deeply necessary.”

The Obama administration’s approach to Africa has also been colored by the issue that has dominated American foreign policy since September 11: counter-terrorism. Grieve Chelwa, the Harvard economist, notes that if Obama’s hands were tied early in his administration with regards to promoting African development, they certainly weren’t when it came to a huge ramping-up of the U.S. military presence in Africa via the U.S. Africa Command, or AFRICOM. Some of the U.S.’s closest counter-terrorism partners on the continent—governments in Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda, and Egypt—have made blatant power grabs and extended the terms of aging leaders, in direct contrast with Obama’s aspirations for Africa’s youth. A kind of Cold War framework of engagement remains in place, in which African countries are seen as dominoes to be protected in the War on Terror. And it’s hard to disentangle whether increased insecurity on the continent has come despite or because of the growth in the U.S.’s military presence.

The irony is that YALI provides a way out of the labyrinth of Cold War–style postures that have plagued U.S.-Africa relations. While there is a Civic Leadership component, it could be strengthened to create a more holistic program that helps strengthen these young Africans’ commitment to civil society and economic liberalism. It would constitute a hands-on approach to a host of ills, from corruption to terrorism.

To be sure, it is still a very modest step. It lacks the high purpose of the Obama administration’s wholesale reconfigurations—or resets, in diplomatic parlance—of how the U.S. engages with countries like Russia, Iran, and Cuba, which involved an active agenda over years to change ossified relationships. But empowering young political activists, and exposing them to the way American political groups organize and make change happen, would be the beginning of a paradigm shift in how the U.S. views its relationship with Africa. These fellows could also be connected to the growing number of African immigrants to the U.S., who through remittances constitute an important aspect of the many African economies.

Mamadou Diouf, director of Columbia University’s Institute for African Studies, says Africans will likely consider Obama to be “the greatest American president of all time.” Still, he concedes that “we need to rethink most issues,” particularly a “rigid approach dictated by the Cold War.” If the YALI program, among others, can help set future administrations on that path, then Obama’s legacy in Africa may only improve with time.