Marina Abramović is obsessed with dividing herself into thirds. When she dies, she wants to be buried in three different places—Belgrade, Amsterdam, and New York—in three different tombs. She doesn’t intend to rend her body into parts; even for a performance artist whose works have often included mutilation, suffocation, abnegation, fasting, extreme denial, and rivulets of blood, dismemberment would feel overly gruesome. Instead, she plans to commission two fake Marina corpses for this act, never revealing which city will be home to her actual remains.

There are other requiem requirements, too: She wants the singer Anohni to warble Frank Sinatra’s “I Did It My Way” plaintively at her grave; she wants her mourners to wear a bright color, perhaps hot pink. She has worked this all out in advance with her lawyer. The funeral, she said in her 2011 lecture “An Artist’s Life Manifesto,” is “the artist’s last art piece before leaving.” She said this three times at the end of her speech in order for it to sink in. For Abramović, three is more than a magic number. Do something twice, and it might be a mistake. Do it three times, and it becomes an intentional act, a performance.

Abramović, who turns 70 this year, is also convinced that she has a trio of separate selves crowded into her towering, magnetic, and still very alive person. She calls them the Three Marinas in her new autobiography, Walk Through Walls, which emerges from the glitzy celebrity memoir imprint Crown Archetype in October of this year: “There is the warrior one. The spiritual one. And there is the bullshit one.” Abramović may be the only superstar performance artist in the world at the moment, and she has brought all three Marinas to her writing. The book itself has the veneer of an ambitious performance piece, as Abramović exposes her deepest personal wounds and places them next to her artistic triumphs, in order to create a kind of epic mythology around her work.

There is always a performative aspect to memoir. The author turns blank pages into a museum of the self, cutting herself open for the sake of the narrative. But in Abramović’s case, the performance feels even more extreme. She has actually bled for her life story, onto pristine gallery floors. She has sat for 700 hours in the same chair willing herself not to sneeze despite bone-crunching pain.

There is no question that her memoir would be both dramatic and deeply controlled, an act of naked exposure and also a narrative that is at times a bit too fascinated with the dazzle of high art. And there are moments in the book, just as there are in her more dangerous performances, when everything goes off the rails and someone has to call a paramedic (or a publicist, but more on that later).

The “warrior Marina” emerges most often when Abramović is recounting her past, as she does in the first third of Walk Through Walls. Born in 1946 to well-off parents in Yugoslavia under Tito’s Communist regime, Abramović claims she became an artist to get away from her mother’s cold, abusive attitude, an absent, adulterous father, and the oppressive, gray sameness that engulfed most of her Slavic peers. She got married young to try to escape, and then wound up back at her mother’s house at 25, where “to protect myself from her, I smeared the contents of three hundred cans of brown shoe polish all over the walls, windows, and doors of my room and studio. It looked as if the room was covered in shit; the smell was unbearable.”

When she looks in the rearview at these formative years, Abramović turns steely. She did what she had to do to get out of Belgrade, and she did what she had to do to keep going. She first attended the Academy of Fine Arts for painting, but began experimenting with her own body as a medium in the early 1970s. She fell in love with the adrenaline and the crowd’s visceral reaction as she put herself in extreme peril. For her first big piece, Rhythm 10, she recorded herself quickly moving ten knives around her hand on a table, often stabbing herself in the process; she then did it again, stabbing herself a second time to the soundtrack of her first recording. When she performed, Abramović felt herself become “a receiver and transmitter of huge, Tesla-like energy. . . . I had felt that my body was without boundaries, limitless; that pain didn’t matter, that nothing mattered at all—and it intoxicated me.” She sounds hulk-like in these passages, completely devoid of fear.

Abramović reaches warrior fever pitch when describing her attitude after completing Rhythm 0, a six-hour piece she performed in Naples in 1975. She laid 72 objects on a table and gave viewers complete permission to use them on her body as they desired. Some of the objects were harmless—lipstick, honey, a rose, a bowler hat—and others were deadly, like an ax, a carving knife, large needles, and a pistol next to a single bullet. At one point during the performance, she recalls:

There was one man—a very small man—who just stood very close to me, breathing heavily. This man scared me. Nobody else, nothing else, did. But he did. After a while, he put the bullet in the pistol and put the pistol in my right hand. He moved the pistol toward my neck and touched the trigger.

He never shot, but he could have. Afterwards, she writes, “I looked like hell. I was half naked and bleeding; my hair was wet. And a strange thing happened: At this moment, the people who were still there suddenly became afraid of me.”

This Marina is the most charming one, the voice that makes Walk Through Walls propulsively readable. This is the magnetism that drew thousands to Abramović’s 2010 MoMA retrospective, “The Artist is Present,” to sit across from her and feel imbued with otherworldly life force (or so their tears would have you believe). This is the swagger that pulls other celebrities who incline toward the provocative—Lady Gaga, Kim Kardashian, Kanye West, Riccardo Tisci, James Franco—into her orbit. It is also only present in one part of the book.

The two other Marinas—the divine and the bullshit artist—start to dominate her narrative from the moment Abramović meets Ulay, né Frank Uwe Laysiepen, a German performance artist who is every bit her creative equal. They lived together for five years in a battered military van with a puppy and no bathroom, literally starving some days for their art. The Marina-and-Ulay saga has become—for those who have viewed HBO’s rosy-tinted documentary on Abramović’s life and work—one of the great romantic epics of modern art. The two made relational works for over a decade: They smashed their bodies against one another until bruised and broken, breathed into each other’s lungs until they nearly passed out, stood still as Ulay held a taut bow-and-arrow aimed straight at Marina’s heart, and finally, in grand operatic fashion, walked toward one another from either end of the Great Wall of China, where they ultimately separated forever. Ulay returns, years later, to take her hand during “The Artist is Present”—a much-memed moment that still elicits swoons and heart-eye emojis in the Tumblrverse.

Abramović writes about Ulay with great tenderness, but admits to the creeping feeling that her star was eclipsing his. The Spiritual Marina was stronger alone than in a pairing. While performing a long-duration piece called Gold Found by the Artists in 1981 (it was later called Nightsea Crossing), Ulay lost 26 pounds, injured his spleen, and found he could no longer continue. But Marina wanted to press on. “My thinking was simply that he had reached his limit, but I hadn’t reached mine. To me, the work was holy, and the work came before everything else.”

She talks about discovering within herself a “liquid knowledge” that can only form when the brain is so tired that something else takes over. This liquid self, Abramović says, allowed her to keep going when Ulay couldn’t. Out of frustration, one day he slapped her. “This was not a performance piece. This was real life.”

This is an important breaking point in Abramović’s self-perception: There are violent acts that are not art, there are desperate moments that are not performance. She needed to get away from shock, and move into something more transcendent, and ultimately commercial. After her split from Ulay, Abramović’s art turns toward giant acts of willpower and resistance. She scrubbed rotting bones for days at the Venice Biennale, lived only on water in a gallery for two weeks (a piece later parodied in Sex and the City), sat in the MoMA for three months. She moved to New York permanently in 2002, where she started wearing designer clothes and appearing at glamorous events with the bearing of a gothic queen. These big moves made her an international sensation as a sort of chic spiritual extremist, a woman who could survive anything in Yves Saint Laurent boots. She also says that internally she was falling apart.

While Abramović is clearly able to endure extreme physical pain for her work, in her emotional life she is not so tenacious. After the split from Ulay, she married a confusing seesaw of a man named Paolo Canevari. (The pair divorced in 2009.) Their relationship caused Abramović to weep in taxis and wear down her closest friends with long monologues, all while she was winning international acclaim and preparing for her grand MoMA show. This confessional side of her can, she says, grate on her confidants; it weighs heavy on the reader, too. Long passages in the book see Abramović lamenting lost love, then going back for even more abuse, then lamenting again.

Of course, the Bullshit Marina, the one who “consoles herself by watching bad movies” and “putting her head under the pillow to pretend her troubles don’t exist” is the most human and relatable. This Marina also happens to be the least interesting. In the latter half of the book, Abramović repeatedly performs her vulnerability. She opens up over and over about heartbreak, neurotic breakdowns, and a week when she had to escape to the woods and watch a shaman kiss her own breasts in order to stop crying (no, really). But that’s the other thing about the Bullshit Self; often it is just performing sadness for the sake of gaining empathy from others. When real empathy is needed, the Spiritual, all-knowing, liquid side needs to take over. And in her memoir, when Abramović confuses the Bullshit for the Spiritual, trouble is never far.

The first proof of Walk Through Walls contained several pages about the summer Ulay and Marina lived with an aboriginal tribe in Australia. They wanted to return to simplicity, a Western primitivist idea about the wisdom of native peoples that is already deeply flawed in its basic conceit. But the way Abramović describes the Aborigines in one passage, as “dinosaurs,” is as problematic and offensive as it gets. “For one thing, to Western eyes, they look terrible ... they have big torsos ... and sticklike legs.... And then there is the smell.”

An early reader posted this passage on Instagram, which led to a media frenzy. Abramović apologized and claimed it was from her diary and did not reflect her current thinking (though nowhere in the first proof did she mention a diary around these remarks). She vowed to remove the passage from the final book, a highly unusual move. Her publicists kicked into high gear, sending out fresh copies of the manuscript scrubbed clean of the controversy. This scuffle became a small performance of its own; an act of penance and shame.

Suddenly Abramović’s once-radical ideas seemed outdated, colonial, a reflection of the white walls of the high art establishment. Her book gives perhaps the fullest account yet of her artistic formation, while also indicating that her time has passed. Abramović paved the way, but she is no longer the future. And she seems to know it. In the book’s conclusion, Abramović vents her frustrations with trying to create an institute to teach the next generation of performance artists her trademark discipline methodology. (Some activities include painstakingly counting grains of rice and walking through the woods blindfolded.) Her own new pieces focus on her death, and what will become of her body and work after she leaves corporeal form.

Walk Through Walls is a backwards waltz, and an attempt to leave some kind of lasting impression behind. It’s in no small part thanks to Abramović that “performance art” is now everywhere. Kanye West has called himself a performance artist. He has in the past hired Vanessa Beecroft—an even more controversial Italian artist, who recently caused an outcry over her tone-deaf fetishization of blackness in a New York magazine interview—to stage his shows. The woman who pretended to be mentally ill and threw crickets over an entire D train car in August calls herself a performance artist. Many invoke the term to describe this election season, claiming that this year’s campaigns have been elaborate (and deliberate) political theater.

These casual claims of performance are both homage to Abramović and a distortion of her work. As she often says, “In theatre, blood is ketchup; in performance it is real blood.” Abramović’s blood and sweat are very real. She carves deep, and you can feel that it hurts. But the Warrior Marina, the one who picks up a knife with no fear, and the Spiritual Marina who clears room in the brain for the knife to keep cutting, wouldn’t feel real without the presence of the Bullshit Artist. Reading her memoir is like watching someone hold a bottle of ketchup in a bloody hand.

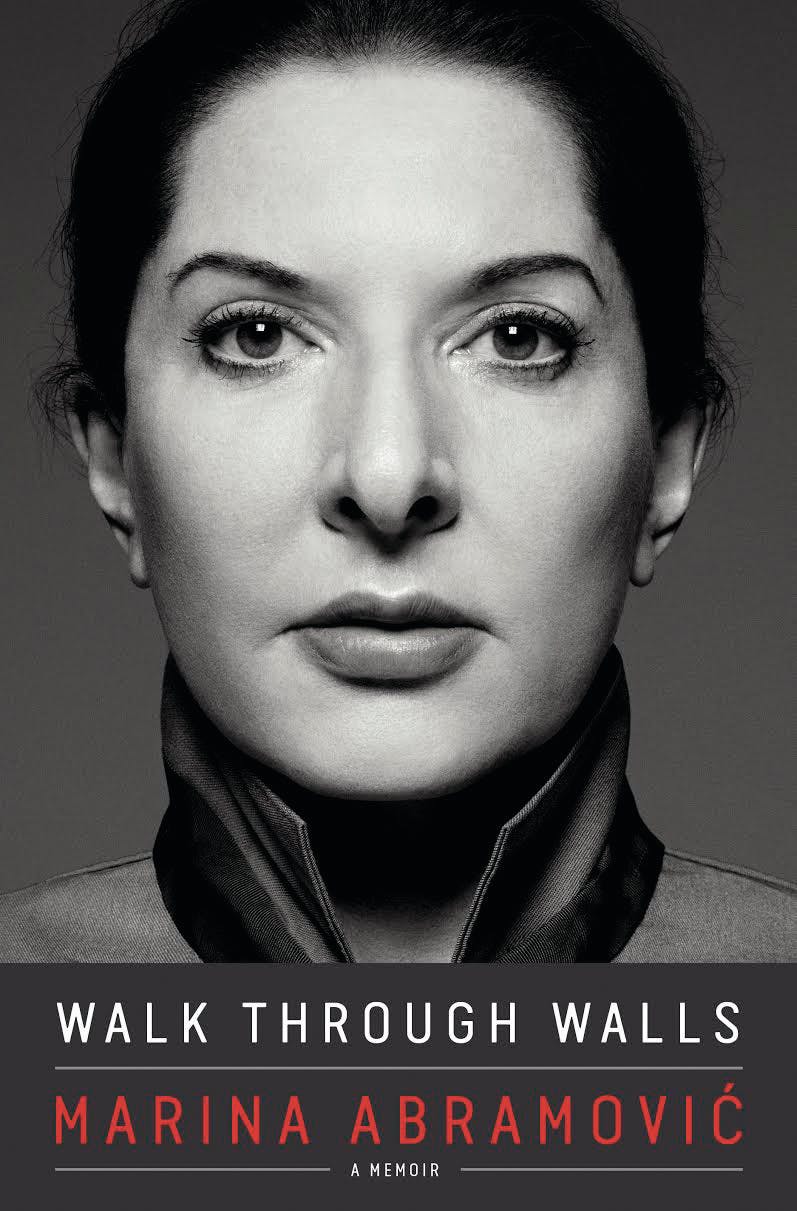

The real and the performative are all mixed up, the pain and the pleasure are intertwined with a winking artifice. On the cover of Walk Through Walls, Abramović stares straight at the reader with a stern gaze, daring you to crack open the book. But if you look closely at the corners of her mouth, you can see that she is about to smile.