As we prepare for another raucous election night, one question remains unsettled between the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton: What accounts for Sanders’s wild success with young women, and Clinton’s relative failure to reach them?

The results of Iowa’s Democratic caucuses certainly indicated a major lead for Sanders among the youth, with the Vermont senator winning 84 percent of voters between the ages of 17 and 29. Clinton, meanwhile, racked up only 14 percent of the vote in that age bracket.

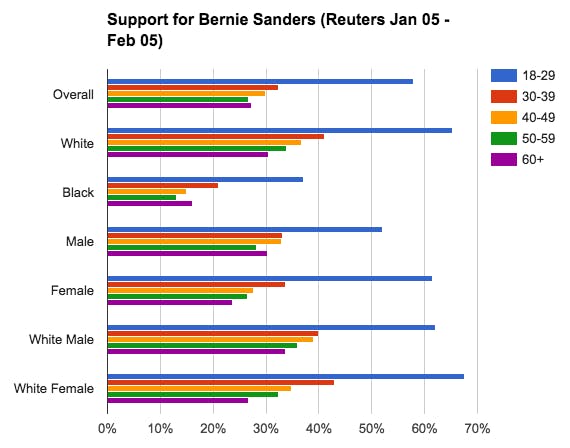

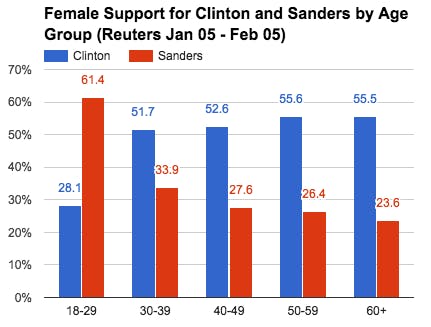

Rolling poll data from Reuters shows that Sanders does especially well among young white women, though he dominates the youth in virtually every group. Taken together, 61 percent of young women support Sanders, versus 28 percent who support Clinton.

There are already several theories circulating to explain the gap between Sanders and Clinton when it comes to young women. Feminist luminary Gloria Steinem said just last Friday on Bill Maher’s show (then somewhat un-said Sunday) that young women are just going where “the boys” are. Author Jill Fillipovic followed up with a riff on Steinem’s thinking in Cosmopolitan, arguing that, “In this primary, Sanders is the guy stuff. Clinton is the girl stuff.” She argued that young women often feel pressured to make a show of liking cool guy stuff instead of lame girl stuff. Democratic National Committee Chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz mused in a January New York Times interview that young women not rallying behind Clinton are merely complacent, while Joan Walsh noted in The Nation that focusing on Sanders taking the lion’s share of youth votes effectively erases those young women who do support Clinton.

To all of this I say: maybe. With a population of millions, reasons are going to vary from person to person, and it’s likely that no single explanation will provide the final word on Sanders’s lead among the young.

But before we find out if Sanders’s youth magic also worked in New Hampshire, allow one young woman a shot at an explanation that doesn’t involve boys or complacency. My theory of Sanders’s lead among, well, people like me—women in their twenties—despite the availability of a Democratic candidate who is also a woman, comes down to three categories.

Precarity. Millennials are all facing precarious futures, but in many ways young women bear the brunt of unstable economies.

Women are likelier than men to lack health insurance, with one in eight women uninsured. And though the Affordable Care Act made great strides for women’s health care, especially in coverage requirements for maternity and newborn care, young women who are still covered as dependents on their parents’ plans may find that they are not insured for maternity care. (Remember, more millennials are living at home now despite some improvements in the economy.) So young women have a sturdy handful of good reasons to support the kind of health care Sanders advocates, namely a single-payer, universal, “Medicare for all” system.

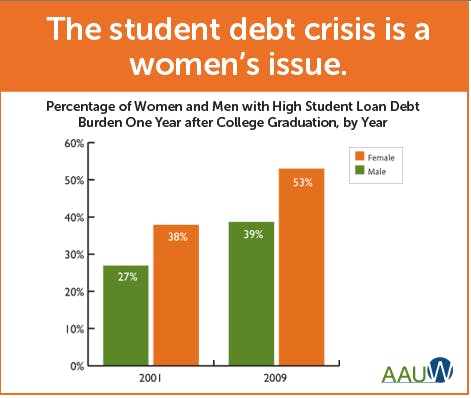

Then there’s the problem of college debt. A report from The American Association of University Women found that in 2009, 53 percent of women college students still bore debt one year after graduation, compared with just 39 percent of men. In August of last year, Jill Fillipovic pointed out in Vice that because more women are first-generation college students from poorer families and make less than men coming out of college, education-related debt is especially dangerous and burdensome for women. For the young student or prospective student, Sanders’s free public tuition plan is likely attractive, and given the gender gap in the college debt situation, especially so to women.

For all these reasons, young people seem far more amenable to the idea of socialism than their older counterparts, and young women especially have much to gain from the democratic socialist-style insurance programs Sanders is presenting.

Memory. You vote based on what you would like to see happen, but what you would like to see happen is based in large part on what has already happened to you. For young people, two world-historical events make up large portions of their biographical memory: the Iraq War and the Great Recession. Both of these slow-burning disasters formed the backdrop against which the generation now aged between 17 and 29 likely evolved their political views and priorities, and their notions of how to advance their own lives and the fortunes of the country through politics.

Unfortunately for Clinton, she is now associated with the Iraq War, though she now says she regrets her 2002 vote in favor of the intervention. Nonetheless, the issue has dogged her campaign since its inception, and Sanders has taken every opportunity to remind his base that he voted against the war and is vehemently opposed to “perpetual war.”

Meanwhile, Sanders also provides a more compelling pitch than Clinton to young people still addled by the overwhelming effects of the Great Recession. With youth unemployment higher than the headline unemployment rate, his message of a rigged, unequal economic system likely has more resonance among young job-seekers. He openly advocates breaking up big banks, widely understood to be the culprits of the economic crash that so recently destroyed millions of lives, and has insisted on taking no money from corporations or banks to support his candidacy. Clinton, on the other hand, has said she will break up big banks only if necessary, and has come under fire for taking hundreds of thousands of dollars from Goldman Sachs in speaking fees. That the premier youth protest movement of our era began as Occupy Wall Street likely doesn’t help Clinton in the millennial association game.

Clinton’s vote for Iraq and her relationship with banks both bespeak her experience: She has indeed been involved in governance for several decades, and has played a role in some of the biggest events to shape America over the last half-century. But millennials tend to prefer, according to a 2015 Harvard IOP poll, integrity over experience, and negative associations are difficult to do away with. Longer-lived people have many more experiences to draw from when forming associations with a candidate and the issues they represent, including, it must be said, Clinton’s primary loss to Barack Obama in 2008, when many in the 17-29 group were still in high school. Older women may therefore have an entirely different set of associations to pair Clinton with, and a different set of resulting desires for her to fulfill. It makes sense, for instance, that a woman who has been politically active for several election cycles to be well aware of (and fed up with!) sexist attacks launched against Clinton over the years; but it makes equal sense that a young woman whose experience with politics is mostly composed of the recent war and economic collapse would view Clinton differently. Neither are wrong, it’s only that their priorities and associations are likely different.

Timeframe. The issue of women’s representation in politics is neither marginal, nor frivolous, nor secondary, but it simply isn’t the case that a young woman must choose between a desire to see a woman in the White House and a desire to secure her own economic future.

Speaking at a New Hampshire rally Monday night, actress and model Emily Ratajkowski (who is 24 years old) put it like this:

“I want a female president so that I can say to my daughter one day, you too can become president of the United States. I believe in that symbolic importance. But I have seen symbolism in election, symbolism that fails the people that so desperately need the action to make change. I want my first female president to be more than a symbol, I want her to have politics that can revolutionize.”

Even Steinem, in the run-up to her more questionable comments on young women Sanders supporters, offered that young women are more active in politics and feminism than ever before. I suspect Steinem is absolutely right (and one gaffe certainly shouldn’t expunge a lifetime of support for young women’s rights). But the key difference between young feminists and older feminists is, of course, age. And with young age comes a longer timeframe within which to achieve the dream of electing a woman president.

But for older women, the picture likely looks different. After watching Clinton herself be defeated in 2008 and, prior to that, an entire lifetime of election cycles in which no woman was even a serious contender, it’s perfectly fair to feel a certain urgency around this particular moment. After all, real up-for-grabs elections don’t come around all that often, and tough, ringer candidates like Clinton are not in massive supply. While young people often feel like they have forever to make something happen, older people have a much keener sense of time. If not now, when? NPR recently reported the recollection of one Clinton volunteer who had just such a run-in back in 2008:

“And she said, ‘Please, I’m 94 years old,’ “ Frederick said. “I can’t get out there and volunteer. Can you please make this happen? And I promised her I would. And it didn’t happen in 2008, and she’s probably not around anymore, but there’s another 94-year-old woman in a wheelchair that I have to do that for this time. And we’re going to make it happen.”

Which is as honorable and genuine a reason as any to put one’s efforts behind Clinton here and now. But it’s equally easy to imagine how the young and the old in this case conceptualize their timeframes, priorities, and futures differently, and how that may contribute to a divide between younger and older feminists that in no way compromises either group’s feminist bona fides. Though the Democratic primary debate is highly pitched, it seems to me this is a rare competition where women will win either way.