On June 14, 1952, a former U.S. navy pilot named John “Buz” Sawyer received a late night phone call from his boss, a Frontier Oil executive named Wright. “Sawyer,” Wright said, “You’re just the fellow we need to handle a little job in Iran.” The job, which involved spraying “a potent new insecticide” in the Iranian countryside to help avert a locust plague, was part of the Truman administration’s Point Four Program of Technical Assistance to Developing Nations, a cornerstone of the liberal anti-Communist approach to the cold war: Win the hearts and minds of the world’s poor by showing them American know-how promised a better future than Soviet central planning. Buz Sawyer cut the ideal American figure to represent the free-market-utopian goals of Point Four: Clean-cut, handsome, humble, and square-jawed, he won over the Iranians not with speeches about baseball and representative democracy, but with respectful displays of can-do pragmatism. With the help of his eager crew, he defeated the locust threat with U.S. chemicals: “I sure hope you boys know something about spraying locusts. I don’t.” (This was 1952, so no debates about organic food or carcinogens.) Iran’s grateful peasantry thus saw with its own eyes America’s bottom-line virtue, and the perfidy of the Soviet Union, when a Russian agent attempted to sabotage Buz’s equipment. “You’re the kind of foreigner I like,” said Ali, a grateful locust control officer. “You don’t criticize my country; you pitch in and help.”

If Buz Sawyer seems a little too good to be true, that’s because he was: He was a comic-strip character, created by the cartoonist Roy Crane. Buz Sawyer appeared in nearly 300 newspapers across the country and was the prism through which millions of Americans understood their government’s actions abroad. Now, thanks to discoveries made in the Syracuse University Archives, where Crane deposited his papers before his death, we know that Crane had a powerful collaborator for his work: the U.S. government.

Before the publication of the Iran strip, a State Department official named Eugene V. Brown sent Crane a ten-page memo, explaining in precise detail the plot points the government wanted for Buz Sawyer, along with what purpose those points served. These included finding a way to “stress [the] importance of Private Enterprise” and to portray “the manner in which Communism attempts to discredit development and improvement programs of the West.” Crane, meanwhile, should do his best to steer clear of certain delicate topics. “It would be best to avoid any reference to OIL in discussing Iran.” Because winning hearts and minds was key, Brown wanted a story showing “a strong bond of friendship” between Buz and an Iranian pilot named Sandhu, the purpose of which was to “provide entry of Buz into local situation on common level with indigenous forces.” (Crane followed this direction, although he used the name Ali instead of Sandhu.) Other plot points were designed to provide “further evidence of machinations of Communism” and “display American individual’s ingenuity in coping with operations.” Six months after the strip appeared, Crane praised Brown’s contribution in a letter to Dean Acheson, Truman’s secretary of state and one of the key architects of the cold war, noting the locust storyline, which was “intended to combat anti-United States propaganda,” was greatly aided by his “cooperation and insight” and “sold me on the Point Four Program.”

The 1952 Iran storyline, published one year before a CIA sponsored coup in the real Iran, was far from the only time Crane depicted the propaganda aims of the U.S. government in comic form. From his creation of the Buz Sawyer strip in 1943 until his death in 1977, Crane was an eager handmaiden to U.S. foreign policy, showing Buz fighting his country’s enemies in Central America, the Middle East, and Asia. From Iran to Cuba to Vietnam, there were few cold war conflicts that Buz didn’t have a hand in.

If it seems odd today that high-level government officials would take the trouble to craft a comic strip, remember that during their mid-twentieth century heyday, newspaper strips had a universal popularity that rivaled that of Hollywood. They were among the most popular features in newspapers, with adults as likely to read them as children. As Edward Brunner, an English professor at Southern Illinois University, is quoted in Pressing the Fight: Print, Propaganda, and the Cold War, newspapers were “powerful delivery systems for information and entertainment,” no section more so than “the funny pages—the one place visited by almost every reader, young or old, urban or rural, rich or poor, overeducated or uneducated.” A 1950 poll by New York University found that 82.1 percent of college-educated newspaper readers read the comics. Crane’s reach was significant: His audience, at its peak, grew to between 20 million and 30 million people. So if you wanted to get out a message—and the government clearly did, and still does, for that matter—comic strips were as logical a place to do it as any. Contemporary entertainers like Kathryn Bigelow (Zero Dark Thirty) and Joel Surnow (24) have been branded as mouthpieces for the U.S. anti-terror agenda, carrying water for the government’s escapades in the Middle East. It’s hard to deny Zero Dark Thirty served up the CIA’s justification for using torture to find Osama bin Laden, and 24 helped normalize the government-friendly idea of torture as an instrument of policy. But—as far as we know!—no one in the U.S. government dictated to Bigelow or Surnow what should be in the work. With Crane, however, we have a clear and well-documented case study in how government officials can micromanage the production of popular culture, a salutary lesson in how propaganda works.

Roy Crane was an accidental cartoonist who became a very purposeful propagandist. He was born in Abilene, Texas, in 1901, the son of a judge and a schoolteacher. His childhood dabbling in comics, including a course he took with the Landon School, a correspondence school that specialized in training cartoonists, stands less as evidence of precocious talent than symptoms of a general preference for any activity, notably doodling, that helped him avoid the classroom. After stints at Hardin-Simmons University, in 1918 and 1919, and the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, he enrolled at the University of Texas, where he won a reputation as a ne’er-do-well whose low marks were matched only by high gambling debts.

Crane dropped out in 1922, and took to the road, riding the rails and panhandling before signing up as a sailor in Galveston, Texas, with a tramp steamer bound for Europe. On shore leave in Antwerp, he arrived late for the ship’s departure and found himself stranded. Making his way to the U.S. consulate, he was able to tap a sailors association fund to pay for his return to New York later that year, where his wastrel days reached their apex in his decision to pursue a career in cartooning.

While doing odd jobs for The New York World, Crane moonlighted as an assistant to H.T. Webster, the panel cartoonist best known for creating Caspar Milquetoast, “the man who speaks softly and gets hit with a big stick.” Aside from high school, the only education Crane had completed had been the Landon School’s correspondence course in cartooning, which turned out to be unexpectedly valuable. Charles Landon, who ran the course, also hired cartoonists for the Newspaper Enterprise Association, a Cleveland-based syndicate that specialized in providing features for small-town newspapers. He offered Crane the chance to do a daily strip.

His first feature, Washington Tubbs II (later shortened to Wash Tubbs) followed the adventures of a young knucklehead as he tried to woo women. Initially only appearing in a handful of small newspapers, Tubbs was a precursor to the teen humor genre that would later achieve its codified form in the Archie comics. Feeling that teen comedy wasn’t his métier, he started sending Tubbs to exotic locales like the South Pacific, where he would get caught up in foreign intrigues, pulp adventures of the sort later glorified in the Indiana Jones movies. This shift in tenor became permanent in 1929 when Crane introduced a secondary character, Captain Easy, a hard-bitten, cynical soldier of fortune. The Captain Easy, Soldier of Fortune strips were particularly influential for later superhero comic books. Superman co-creator Joe Shuster cited Crane as an influence on his style.

Crane’s Captain Easy storylines featured broadly populist politics and characters who participated in revolutions in Latin America and Europe, supporting poor peasants fighting oppressive landlords. But even as Crane was hitting his stride as an adventure cartoonist, he started to feel guilty about doing work that lacked a moral dimension. In 1940, as the United States inched toward war with Germany, Crane first started to think about ways his strip could be a tool to engage with important issues of the day. With isolationism and interventionism hotly debated, newspaper editors wanted comics to remain strictly neutral. Along with only a handful of other cartoonists, Crane broke from this policy by creating storylines that insisted the European war couldn’t be avoided. In 1940, for example, Captain Easy tangled with a ring of German saboteurs (one of the top spies is named “Otto”).

“Those in Washington have almost overlooked one of the niftiest propaganda mediums to be found in the USA—newspaper comic strips,” Crane wrote in a 1942 letter pitching his services to Elmer Davis, director of the United States Office of War Information. “On my own initiative, I began some propaganda work about two years ago, in an effort to wake people up to the danger confronting us. It was necessary to be pretty subtle as office regulations did not permit any mention of war.” Crane suggested the government set up a department and coordinator who could tell cartoonists which themes they should integrate into their narratives.

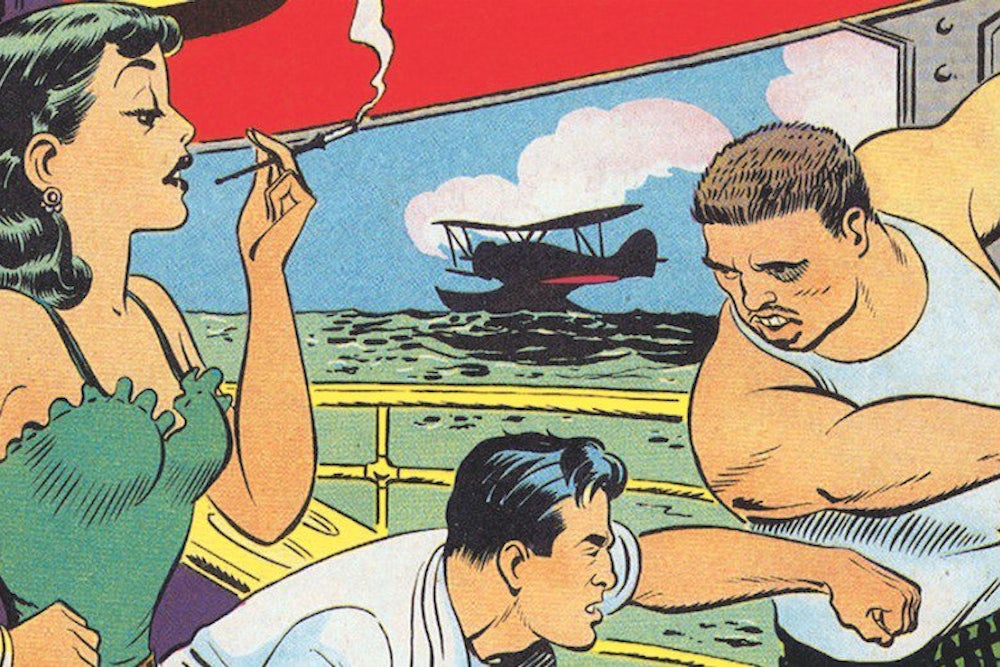

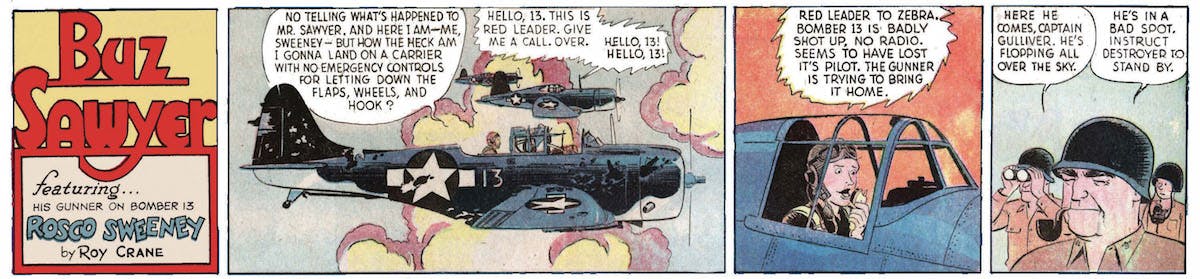

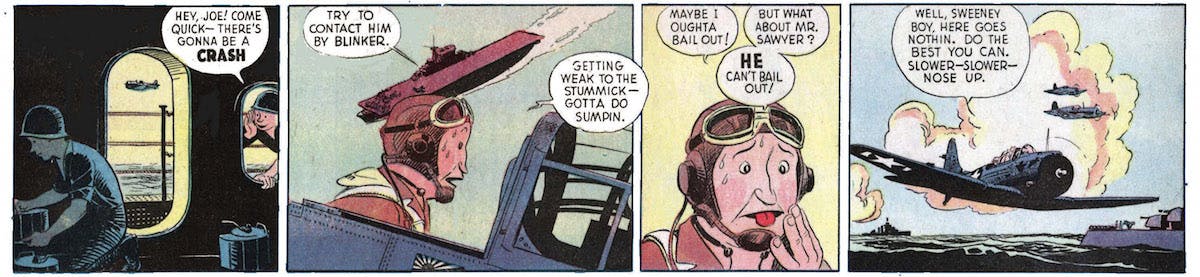

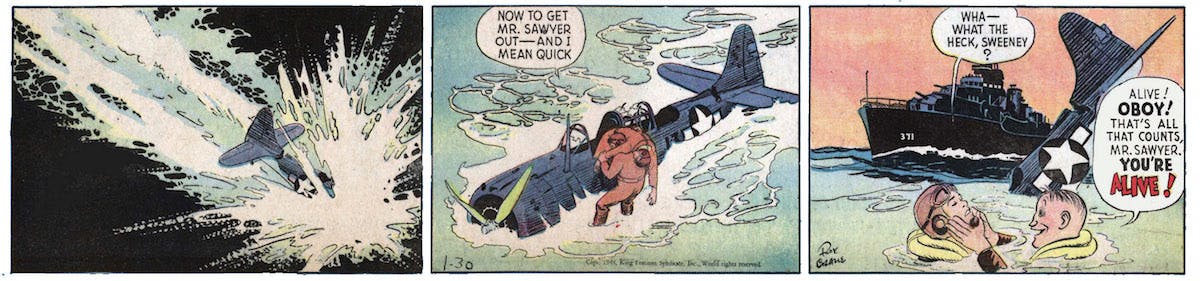

In 1943, Crane stopped producing the Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy features and signed a contract with the King Features Syndicate, which had guaranteed him a minimum of $1,000 per week and an ownership stake in whatever new feature he wanted to develop. Crane’s move to King Features was largely motivated by the lucrative compensation, but it was also in alignment with his commitment to pro-war propaganda. His newest creation, Buz Sawyer was, unlike Captain Easy (who to put it mildly, liked the ladies), an unambiguous embodiment of virtue. “Buz Sawyer doesn’t smoke, he doesn’t drink, he doesn’t gamble. He leads rather an exemplary life,” Crane said in a 1961 radio interview with fellow cartoonist Vernon Greene (who worked on the strip Bringing Up Father). “The comic strip is … a public responsibility. It may be judged by the uses made of it, whether good or bad, like dynamite. Personally I get a lot of satisfaction in thinking I’m an influence for good.”

Crane wanted to work with the Navy from the start of Buz Sawyer, but it took him a year to earn the military’s trust, after which they enthusiastically provided him help with the strip. On January 21, 1944, a naval lieutenant named Harold B. Say wrote to Crane about the Buz Sawyer strip, asking him to alter the way “natives” were depicted. “The Navy Department would appreciate it if you would refrain from using material showing direct military assistance to Americans by natives of the islands of the South Pacific,” he wrote, on the grounds that it might endanger American nonmilitary allies among these populations. The next letter, dated February 4, 1944, from another naval lieutenant J. Clarke Mattimore, described the Navy’s difficulty convincing sailors to become aviation radio men—perhaps there was something he could do about it. Two months later, Buz was trying out a new plane with his sidekick Rosco Sweeney when he delivered an impassioned speech on the importance of radio men. “Who handles radio, and the rear guns, and protects my worthless neck?”

In the hyperpatriotic atmosphere of World War II, there was nothing unusual about Crane’s work with the Navy. Other cartoonists and entertainers were doing the same thing. One Disney strip showed none other than Mickey Mouse dropping a bomb on Berlin. This was the era when directors such as Frank Capra took time off from feature films to produce propaganda documentaries like the Why We Fight series. But unlike these other contributors, Crane’s propaganda efforts continued after the war. He maintained his close ties to the Navy and later expanded to other branches of government. Politically, Crane became something of a hawkish cold war liberal, which made him especially eager to work with the State Department. The Truman administration intended to open a front against communism by sending U.S. technical ingenuity abroad to help solve problems of hunger and disease, a policy made official under the Point Four Program. “Communist propaganda holds that the free nations are incapable of providing a decent standard of living for the millions of people in underdeveloped areas of the earth,” Truman said in 1950. “The Point Four Program will be one of our principal ways of demonstrating the complete falsity of that charge.” Point Four sent American scientists and aid workers to countries like Brazil and Iran, where they worked to eliminate malaria, improve irrigation, and introduce modern agricultural techniques. The program was a direct precursor to the Peace Corps introduced by the Kennedy administration. The belief that foreign aid was the best way to forestall revolution was very much in keeping with the populist strips Crane had done in the 1930s, so he had a natural affinity for the idea.

Crane closely followed the instructions the State Department provided to glorify Point Four, including creating a romantic storyline set in India: “The love interest might be worked in by having some beauteous Indian female social worker arrive in the village after a day or so in which the local Indians took care of Buz but were unable to converse with him because he was the first non-Indian they had seen.” Another Iran plotline went nuclear: “In talking to the U.S. Public Affairs officer at Tehran last week about ‘incident’ material,” the State Department’s Brown wrote in June 1952, “he suggested the explorations for uranium as a possibility. For example, the Iranian pilot cohort of Buz could be a geology student who has studied in the U.S. and is now taking further advanced studies in a school at Tehran under sponsorship of U.S. educational program. Because of his extensive knowledge, he may be sought after by Russian-inspired communist exploration parties working undercover in the mountains. Perhaps an attempt might be made to kidnap him, or he may actually be kidnapped.” Crane didn’t follow this particular lead; his actual storyline is much tamer than Brown’s imagined one. Ironically, the State Department bureaucrats wanted wilder plots than the cartoonist was willing to work with.

Crane liked to believe he was in the “mass entertainment business”—as he told Vernon Greene in 1961—but the type of entertainment he provided was designed to deceive the American people. The millions of Americans who read Buz Sawyer in 1952 would have gotten a very distorted image of Iran. They would have seen a country where Americans were chiefly helping to avert a famine, where the major threat of disorder came from Soviet spies, where Americans were good-hearted aid officials, where control of the oil supply wasn’t a factor, and where the U.S. government had no conflict with the democratically elected government.

It seems the State Department deceived Crane himself on one crucial point. As Crane complained to Secretary of State Acheson in 1953, the original “plan” was to take the locust storyline and turn it into a comic book to be distributed in Iran. Crane said it was “disappointing” that “nothing has been done” to carry out this plan. “If such a story, intended to combat anti-United States propaganda abroad, has any merit, it would seem to deserve greater foreign distribution than the few dozen papers carrying Buz Sawyer in Scandinavia and Latin America.” Perhaps Crane was being naïve here. The storyline wasn’t really aimed at fighting propaganda abroad but rather in spreading it in the United States.

Crane remained credulous about U.S. government claims about Communist plots even as the cold war consensus broke down. While no longer getting direct orders from the State Department, Crane remained in close contact with high Navy officials, who were always eager to use him as a megaphone for their worldview.

In 1961, Crane took a two-month trip to Asia, where he visited naval stations and rode with the China patrol that guarded the waters between Taiwan and the mainland. During this trip, he met with Admiral C.T. Griffin, commanding officer of the 7th Fleet stationed in the Far East, who wanted to recruit the cartoonist for the next big foreign policy adventure. “Crane, the Far East or Southeastern Asia is extremely important if for no other reason than it contains almost half of the world’s population,” Griffin said (as Crane recalled in the Greene interview and in a note among his papers at Syracuse). “We’ve already lost China to the Communists. If we should lose Laos and Vietnam, it could be that Burma, India, Iran, the Philippines, Japan, even Australia and New Zealand could be lost to the Communists. It’s very important to hold what we have. The problem is that the people back home don’t really know what’s going on. It’s five times easier to get into the newspapers news of Europe than it is news of Southeast Asia. Crane, if you could help acquaint the reading public back home with what is going on here and the problems and the importance of it, I think you’d be doing your country a great service.”

Crane followed Griffin’s suggestions and started doing strips showing Buz fighting Communist plots in Asia and Cuba. In one 1962 storyline, Buz goes to Hong Kong and Japan to fight Communist drug smugglers, after receiving a briefing where he’s told that “the policy of Red China is to suppress the use of narcotics at home while smuggling heroin to other countries. The proceeds of this dope traffic are used to finance Communist activities throughout the world.” During his Hong Kong jaunt, one of the Communists injects Buz with a hypodermic needle full of heroin, nearly causing him to die of an overdose. In Japan, Buz, working with a Lieutenant Katawa, discovers that a leading Communist named Miyake sells drugs “to underworld agents, raise money for party.” Later that year, Buz and his wife, Chrissy, help a refugee family fleeing from Cuba.

As Crane grew more strident in his cold war politics, he was increasingly the target of complaints that the propaganda was being laid on too thick. In 1962, Toronto Star editor Jim Cherrier sent King Features a letter complaining about a Buz Sawyer strip on Communist China and the international opium trade. Cherrier went to the trouble of investigating this claim and concluded that there is “little evidence” that “China is drugging the world to collect funds for its subversive works. … Furthermore, we strongly object to putting comics in political propaganda use, whether for Communist or anti-Communist propaganda,” Cherrier wrote. “To many children, comics represent one of the main sources of reading for diversion. We are consequently all for keeping the cold war out of them. We like Buz Sawyer and our readers like Buz. However, we wonder what can be done about this story’s veracity and future stories from Roy Crane.” King Features executive Sylvan Byck tried to dismiss the Toronto Star letter in a note to Crane by speculating that “some of the restiveness among Canadian papers stems from the fact that the Canadians are doing a lot of trading with China.”

But it wasn’t just Canadians who were grumbling about Buz Sawyer. In 1963, Ben F. Reeves, managing editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal, wrote to King Features to say his paper was going to drop Buz Sawyer. “The current Cuba sequence … has gone on since last October through a series of dreadfully monotonous escapades,” Reeves complained. “Worse still, the propaganda contained in the strip is of the most blatant sort, utterly without grease, grace, or subtlety.”

Crane was clearly hurt by Reeves’s letter, a copy of which was forwarded to him by the newspaper syndicate. Among the cartoonist’s papers at Syracuse, there are six pages of foolscap notes on which he tries to answer the Kentucky newspaper editor. It is unclear whether these notes ever coalesced into an actual letter, but they show a wounded Crane trying to justify himself. In one instance, he referred back to the conversation he had with Admiral Griffin in 1961:

Two years ago we did two things we believe are unprecedented for a cartoonist. 1) We spent over two months in the Far East gathering story material. 2) When it became obvious that the dangers of a Communist “take over” of Southeast Asia was much greater than people back home believed, we attempted three stories to inform the American people of the dangers and consequences. We acted as a foreign correspondent. Thus we dramatized the news in the form of a story. This was a calculated risk, conceived as a public responsibility, that might cost us readers, papers, and money.

As the Vietnam War heated up, Buz gave his propaganda a militaristic twist. A 1966 strip showed an American pilot returning from a mission to drop napalm bombs. In response, the Soviet state publication Pravda denounced Buz Sawyer, accusing Crane of justifying napalm bombing and trying to convince kids “of the necessity and the just character of the aggression in Vietnam.” But even those who disagreed with Pravda’s politics felt the Buz Sawyer strip was going too far. As Crane admitted in a letter he wrote to the archives at Syracuse late in life, “several prominent newspapers” dropped him because they thought he was too politically strident.

In truth, Crane’s greatest period as a cartoonist was the ’30s, when his Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy stories were sprightly and vigorous and full of wanderlust. As Crane became more concerned with tailoring his strips to a political message, they lost the spark that had once made them special. If Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy possessed the rousing energy of the original Star Wars trilogy, late-period Crane was the didactic and lecture-y analogue of the unfortunate prequels that followed them.

The Buz Sawyer material remains fascinating as a historical artifact, a window into how the government sold its ideas to civilians. But ultimately, Crane’s artistic career was a casualty of the Cold War, undermined by his own sense of responsibility. Crane, and Buz Sawyer, lost favor as the tone of American popular culture shifted in the ’60s and ’70s, and by the time of his death in 1977, neither was a major force. Toward the end of his life, Crane had handed off most of the duties of writing and drawing to assistants. Perhaps he could no longer find the satisfaction of knowing he was an influence for good.