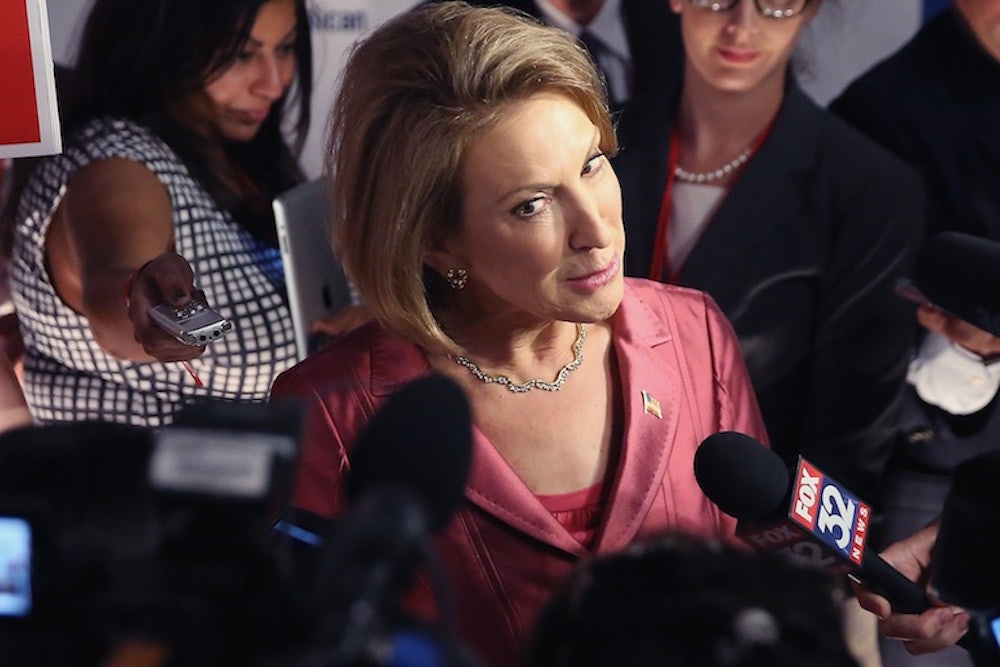

Over the weekend, Republican presidential hopeful Carly Fiorina followed up her much-lauded debate performace with a CNN appearance in which she came out against any federal mandate regarding paid parental leave: "I don't think it's the role of government to dictate to the private sector how to manage their businesses," she told CNN's Jake Tapper, "especially when it's pretty clear that the private sector, like Netflix, like the example that you just gave, is doing the right thing because they know it helps them attract the right talent." But Netflix itself disproves Fiorina's theory that the free market, if left to its own devices, will do "the right thing" when it comes to paid parental leave.

Netflix was rightly applauded last week for its decision to grant unlimited maternity or paternity leave to its employees for the first year after having or adopting a child. But the new policy does not apply to employees in Netflix’s DVD division, the Huffington Post’s Emily Peck reported on Thursday. In contrast to the generally salaried workers of Netflix’s streaming division, Peck explained, “Most of Netflix’s DVD workers aren’t highly sought-after, high-skilled engineers.” That accounts for the disparity in their benefits package: An anonymous worker told Peck that the DVD division's policy is one month of paid leave, with the option of further leave at reduced pay.

Because the United States is one of just a few nations that don't guarantee its workers paid parental leave, policies like Netflix’s function as attractive benefits to draw highly skilled workers to well-paid jobs. In other words, our abysmal national policy on maternity and paternity leave—the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 only guarantees 12 weeks of unpaid, protected leave—ensures that secure, fully paid time off with a new baby is a privilege only some workers possess, despite the fact that all babies (rich or poor) need equal care in the earliest stages of life. That gap between paid leave policies for upper-tier workers and those for the rest of the workforce has several obvious negative effects, not least that it punishes babies for the income level of their parents.

But there are more insidious effects, too. First, the gap between the best and worst parental leave policies encourages well-to-do workers with generous parental benefits to resist any national efforts to assure workers a standard amount of paid leave. The conservative think tank YG Network (now known as Conservative Reform Network) seemed to realize this potential in an anti-parental leave screed it published in its 2014 policy packet “Room to Grow,” where it criticized the FAMILY act, a piece of legislature that would ensure protected leave and a stipend during time off.

“Proponents claim [the FAMILY act] would inexpensively provide needed assistance to those lacking paid leave, and would particularly benefit women by providing paid maternity leave. But while it would assist some women, it would also disrupt the employment contracts of the majority of working Americans who currently have leave benefits. This new federal entitlement would encourage businesses currently providing paid leave programs—including more generous leave packages—to cease doing so.”

As the argument goes, a federal law guaranteeing protected, paid leave for parents could cause some employers currently providing cushy maternity benefits to reduce them to merely meet federal standards. This law could feasibly reduce the benefits of some women with the kinds of high-earning jobs that tend to come with generous leave policies; on the other hand, the fact that parental leave does function as a perk suggests a federal minimum available to all workers likely wouldn’t do all that much damage to extant policies. Nonetheless, the fact that parental leave is treated as a privilege to earn, like year-end bonuses and sweet parking spots, provides fuel for this kind of rhetorical move against parental leave for all. Don’t support universal parental leave, moms and dads, or you might get stuck with the same measly benefits the poor workers have to deal with.

Perhaps more concerning yet is the pacifying effect that highly publicized but ultimately limited paid leave policies have on national policy. When companies like Netflix and Microsoft—joined on Monday by yet another tech company, Adobe—roll out brand-new parental leave policies, they generally don’t point out that many workers at other companies are still more or less on their own when it comes to taking time off to care for infants. But the veneer of free-market beneficence allows politicians like Fiorina to suggest that federal intervention in paid leave policy isn’t necessary because companies seem to be "doing the right thing" on their own.

They are not. As Caroline Fredrickson points out in her 2015 book Under the Bus: How Working Women are Being Run Over, “According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 11 percent of the workforce has paid leave—that means the other 89 percent are left to their own financial resources (if, indeed, they have the right to take leave at all). According to one survey, almost three quarters of workers with an income below $ 20,000 per year did not have paid leave, as opposed to only one quarter of employees whose income fell between $ 50,000 and $ 75,000.” Fredrickson cites a 2012 study by the Department of Labor that found 46 percent of workers who wanted to take time off were not able to because “they could not sustain the loss of wages.” However promising the policies of companies like Netflix might be for some of their workers, those earning less in lower skilled positions don’t seem to be getting in on the progress.

So it’s time to re-conceptualize parental leave. Rather than thinking of it as a perk due to some lucky workers (Congratulations! Your skills are rare enough to earn you the right to nurse your baby!) we should think of it as a period of care due to all infants. Since all babies require the same care as they arrive in the world, all parents should be assured the protection of time off and the stability of continued pay while they look after their newborns. The fact that so many families lack the ability to take time off to care for their infants illustrates how keenly income inequality is felt, even in the earliest moments of a child's life. All of the American Dream rhetoric undoubtedly to come during the 2016 election season cannot conceal the fact that poorer kids simply start off with less, a condition that can only be remedied by giving their parents more.

This article has been updated.