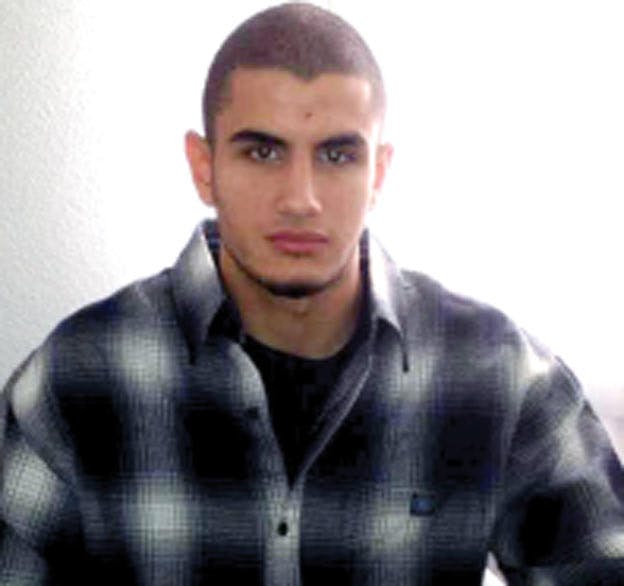

At approximately 3:30 p.m. on February 14, Omar El-Hussein cut down a back street in Østerbro, a quiet neighborhood near the center of Copenhagen. Dressed in a bulky black parka, the 22-year-old strode purposefully toward the Krudttønden cultural center. As he approached, he withdrew an M95 assault rifle from a bag.

Inside, a panel discussion was under way on blasphemy and freedom of expression. It featured Lars Vilks, a Swedish cartoonist who had been living under police protection since 2007, when he published cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad with the body of a dog. Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, now the self-proclaimed caliph of the Islamic State, had announced a bounty of at least $100,000 on Vilks’s head (more if he were to be “slaughtered like a lamb”). Earlier in the day, the café had been swept for explosives, according to an official Danish Ministry of Justice report. A heavy security detail–two Swedish bodyguards, two uniformed cops, and three agents from Denmark’s security and intelligence service (PET)—scanned the guests as they arrived.

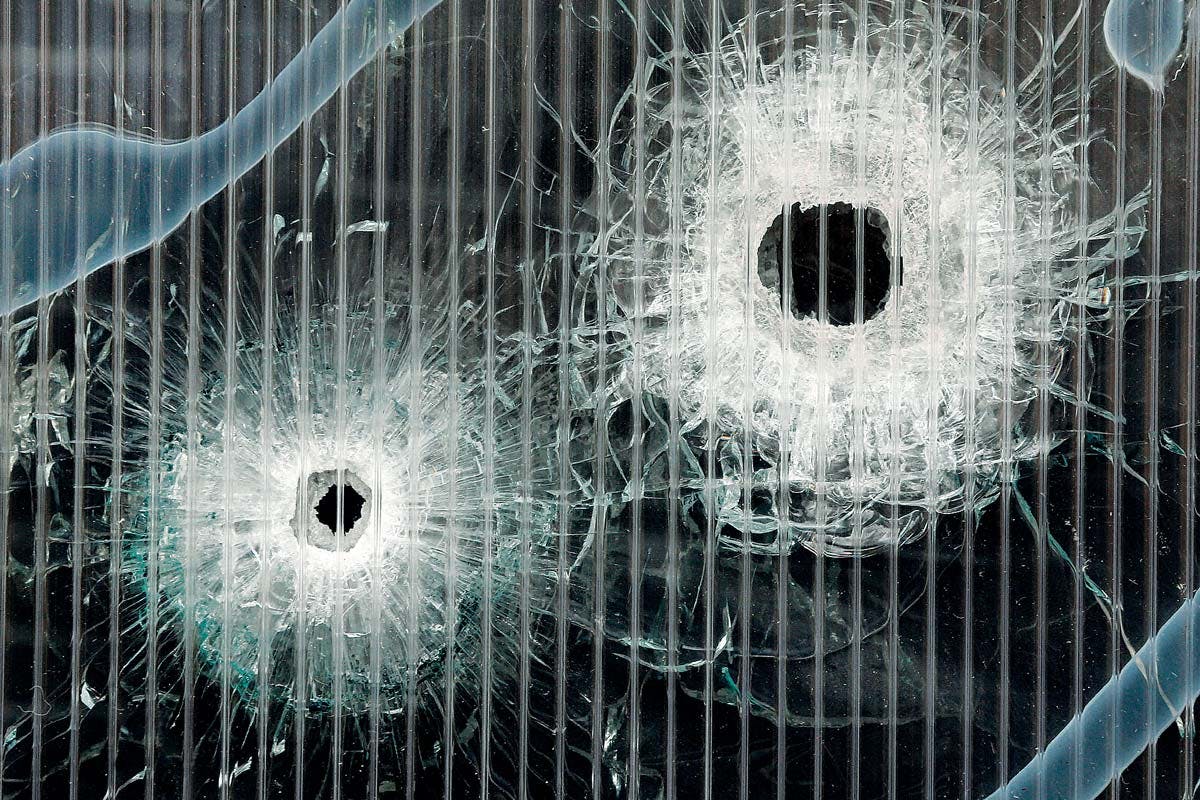

El-Hussein headed for a rear entrance. The back door was locked, so he circled back to the front. There, standing about six feet from the center’s glass facade, he opened fire.

Inside the lecture hall, one of the bodyguards ordered the crowd to move to the back of the room. He pushed Vilks and Helle Brix, a Danish writer and journalist known for her criticism of Islam, into a storage room and locked them in. Some members of the crowd escaped out the back of the building. Others tried a door at the front, to El-Hussein’s left. He wheeled toward them, and they snapped the door shut before he could shoot.

Investigators would later announce that El-Hussein fired at least 28 rounds, some during that first burst through the window, and then, according to one witness, as he coolly held the front door open and fired a second volley. Two security agents were struck by bullets, and two more were injured by shattered glass. All four survived. Several agents managed to return fire, but there is no evidence that they hit El-Hussein. In the street, bystanders worked to save the life of Finn Nørgaard, a 55-year-old filmmaker who El-Hussein had shot through the back, but he was declared dead upon arrival at the hospital.

El-Hussein made his escape after only a few minutes, cutting through backyards for two blocks, until he encountered a woman waiting for her boyfriend in the passenger seat of a Volkswagen Polo, keys dangling in the ignition. Hussein forced her out and stole the car. He drove to a nearby school, ditched the vehicle, and then called for a taxi.

There is no understanding El-Hussein—let us state that in advance. It can be foolish to attempt to plumb the depths of what motivates someone to murder people he doesn’t know, even if a political motive seems to exist.

El-Hussein’s attack came just weeks after the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris, and the parallels between the two incidents seem clear.

In the aftermath, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, the Danish prime minister at the time, said her country was waging “a fight for freedom against a dark ideology.” President Barack Obama called Thorning-Schmidt to pledge his support for Denmark in the struggle against violent extremism.

Yet how did El-Hussein come to feel such a sense of dislocation and hatred for the greater society he was born into?

The taxi deposited El-Hussein at Mjølnerparken, the low-income housing project where he had been born and raised and where his assault rifle would later be found on a soccer field. At 4:15 p.m., according to the Danish newspaper Politiken, El-Hussein entered a nearby apartment. He stayed there for 20 minutes, changing his clothes to disguise his appearance. After that, Danish news reports state that at 10 p.m. El-Hussein spent 30 minutes at a local internet café.

Again El-Hussein disappeared, this time until 12:41 a.m., when he surfaced outside Copenhagen’s Great Synagogue, the center of Jewish life in the city. A Bat Mitzvah party was under way in the synagogue’s community center. Two policemen, their machine guns hanging loosely by their straps, stood guard outside. El-Hussein stumbled toward the men, pretending to be drunk.

At that moment, a 37-year-old security volunteer named Dan Uzan joined them in front of the building. El-Hussein produced two handguns and fired at least six rounds at the guards, killing Uzan with a shot to the head and wounding both officers. One of the policemen was able to return fire—a single shot, which missed.

El-Hussein managed to get away again and was free within the city until about 5:00 a.m., when police caught sight of him in Mjølnerparken on a live surveillance feed. Police scrambled quickly to the scene. After they reportedly called out to him to surrender, El-Hussein responded by opening fire and was gunned down.

Like the shooters in Paris, El-Hussein was clearly a troubled young man. But he was also something more: a Muslim in a formerly ethnically homogeneous European nation that is now decidedly less so, and struggling with it.

The roots of Denmark’s elaborate social housing market, which today accounts for about 20 percent of the country’s total housing stock, dates back to the early twentieth century, when philanthropists and politicians sought to eradicate abysmal living conditions by building quality public housing. It was a noble endeavor, but for most of the following century it took the form of industrial-scale, one-size-fits-all modernist affairs, comparable to projects in East London, the Paris suburbs, or America’s inner cities. These looked and, in some cases, came to function like concrete boxes, separating their inhabitants into insular communities.

In time the limitations showed. In the 1960s, Denmark experienced its first major wave of non-European immigration, as guest workers from Turkey, Pakistan, and Morocco came to fill jobs in an expanding manufacturing sector. Lacking the resources or networks to secure housing in the private market, many were slotted into social housing—as their relatives were a decade later, amid the economic toll of the 1970s oil crises, when immigration controls were ratcheted down and family reunification became the main channel for non-European immigration.

When it was built in 1987, Mjølnerparken boasted some 600 relatively large one- to three-bedroom apartments, centrally located near Nørrebro train station, equipped with balconies, terraces, and elevators. But it quickly became a hub for immigrant families, and those with the resources to move soon took flight.

Its transformation coincided with a new immigration trend, beginning in the 1980s, in which family reunification would be overshadowed by the arrival of refugees from war-ravaged Muslim countries like Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Bosnia.

In a historically homogeneous country uncomfortable with public displays of religion, it was also the start of a continuing debate—many Danish Muslims would call it an anti-Muslim discourse—about the place of religion in Danish society.

Together with Jens Beck Nielsen, a 38-year-old Danish journalist for Berlingske, a top Danish newspaper, I retraced on bicycle the path of El-Hussein’s escape one afternoon in April. We passed the modest four-story brick building where El-Hussein’s mother and brother live—no one answered the doorbell—and proceeded down a main thoroughfare lined with housing projects. Nielsen pointed out a distant minaret, a new 75,000 square-foot mosque funded with approximately $27 million from the former Emir of Qatar, which has generated considerable controversy in the city. We stopped across the street from Mjølnerparken—a complex of brick walls, manicured lawns, and sports fields.

El-Hussein was a member of a gang, a group called the Brothas. Outside the group’s clubhouse, located in the basement of one of the buildings in Mjølnerparken’s housing block, we met two of his friends: Abdurramadan, a thin 19-year-old wearing a parka and a short beard of wispy scruff, and Ahmed, a slightly cherubic 20-year-old with a flat-brimmed Yankees cap and a camo shirt beneath his baggy black jacket. (Police had also questioned Ahmed and searched his home in connection with the attacks, and he requested that I not use his real name. “Ahmed” is a pseudonym.)

Mjølnerparken’s residents have long mistrusted journalists, feeling the Danish media have painted an unfair portrait of the community. That siege mentality had clearly deepened since the shootings. The police were still raiding homes and had recently arrested five of El-Hussein’s friends, including his younger brother, on charges related to procuring and hiding his weapons.

“Omar taught us one thing,” Abdurramadan said. “It’s us against the police.”

No one fully understands El-Hussein’s motives, and he acted alone, the young men insisted. Yet even if his actions were horrific, they were in some ways almost inevitable, they said, a consequence of a society that views Muslims as second-class citizens.

“He was a good man,” Ahmed said of El-Hussein. “We’ve all known him here since we were kids.”

“We’re all good people like him,” Abdurramadan continued. “But when people put pressure on us … then you explode.”

Abdurramadan, speaking in a mixture of Danish and English, explained the implicit racism in Danish society—the way the police treat Muslims and politicians talk about them, the way cartoonists lampoon their prophet and call it freedom of speech, and how the military joins U.S.-backed combat operations across the Muslim world. “The government is against us,” he said. “Straight up: Those who depict our prophet, we’ll blow them up.”

Ahmed said that any Muslim could understand why El-Hussein tried to kill Lars Vilks. In Denmark, he concluded, freedom of speech is just an excuse for pissing on Islam. “How can you call that art? You can’t,” he said. “When have we held the Bible in our hand and put it on the grill and burned it up?”

Søren Rosenberg, a former beat cop in Mjølnerparken who is now a social worker there, said the young men’s heated rhetoric shouldn’t be taken strictly at face value. Their bluster disguised an element of shock. But the sense of some inevitable conflict had been building, especially after Israel’s offensive in Gaza last summer, which particularly angered El-Hussein, and Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard’s continued provocations, which many in the group agreed would justify his murder.

“I’m sure they fully understand what he did,” Rosenberg said.

Social workers who counseled El-Hussein’s gang associates and childhood friends had told me that, amongst themselves, members of El-Hussein’s circle admit that there had always been something off about him, an extremism to his political views, maybe even some underlying mental instability—a sense heightened when he was stoned. But in front of two journalists they seemed eager to portray their friend, who had recently become the “anti-citizen”—Public Enemy Number One—in a less hostile light.

“He is completely normal, just like the rest of us,” Abdurramadan said. “If you say Omar is crazy, then you are saying that all of Mjølnerparken is crazy.”

Like many others in Mjølnerparken, El-Hussein was born here to parents of Palestinian ancestry. At age 14, his mother took him back to Jordan for three years—a break from the path of juvenile delinquency he had started down. When El-Hussein returned to Denmark in 2009, it seemed as though the intervention might have worked. He talked of staying straight and joined a Thai kickboxing gym, throwing himself into the sport to stay focused. Before long, however, El-Hussein was arrested for burglary. Convictions for theft and possession of knives followed. Over the next few years, he bounced between stints in prison and various institutions. At one point during that time, Abdurramadan and El-Hussein shared a flat together. El-Hussein was serious about kickboxing, eating healthy to keep fit. He was a good roommate, Abdurramadan said, the kind of guy who would take the initiative to clean the apartment himself without a word—nothing like the image of the degenerate gangster circulating in the press.

Abdurramadan described his friend as intelligent and, above all, respectful. For all the seemingly impulsive violence that El-Hussein could direct at strangers when provoked, he would never disrespect a friend.

And he always played his cards close to the chest. Abdurramadan remembers a day the two were hanging out on the street, talking. El-Hussein left for a bit. When he came back it was behind the wheel of a car he’d purchased in the interim, without a word of warning.

Lotte Akiko Nielsen, a teacher who tutored El-Hussein one-on-one during the summer of 2012, confirmed his friends’ sense of a young man trying to get his life together. She worked with him to fill in the gaps in his educational record from the years he had been in Jordan. He was polite, she said. It was clear he was someone for whom respect was paramount.

Once, when she praised his writing and told him he was going to do well on his exam, a smile lit up his face. He reached out and shook her hand. It was a deal. He appeared to have “very high moral codes by which he judged himself and others,” she said.

But El-Hussein also “turned his anger inward,” Nielsen said. When conversation turned to the Israeli-Palestinian dispute, for example, El-Hussein grew “pretty dark.”

One time she asked why, since he seemed happy when he talked about his time in Jordan, he had returned to Denmark. He told her he was born and raised here. It’s where his friends are. “He could see himself going back at some point, but he considered himself Danish,” she said. Nonetheless, she had the sense that “circumstances made it hard for him to live here.”

In early 2013, El-Hussein was arrested for stabbing a stranger on a train. In court he described being high and feeling paranoid and thinking he recognized the man as someone who had previously attacked him. A court psychiatrist, however, found him “mentally enlightened” and ruled out the need for any further mental health assessment.

Two years later, El-Hussein would emerge from prison a changed man. Outwardly, he was all smiles, exceedingly happy to see his old friends. He visited a job center for help finding work and an apartment. But he was also quieter, more distant.

“It was really undercover,” said Ahmed. “He didn’t show people there was anything wrong.” In retrospect, Ahmed believes that his friend left prison with a plan. “He knew he was going to die,” he said.

Before the attack, the country’s security apparatus was focused on the threat that Danish citizens radicalized in Syria would return to wage attacks at home. PET estimates that at least 115 Danes have joined the fight in Syria since the start of the civil war there in 2011, making Denmark, on a per capita basis, one of Europe’s largest exporters of foreign combatants to the conflict (second only to Belgium). At least 22 of them came from the port city of Aarhus and attended the Grimhojvej mosque, which has refused to denounce isis and where one former preacher, who had traveled to Syria, was placed on a U.S. list of suspected terrorists with ties to Al Qaeda last fall. At a Berlin mosque last summer, Abu Bilal Ismail, one of Grimhojvej’s imams, exhorted Allah to “destroy the Zionist Jews, they are no challenge to you. Count them and kill them to the very last one.”

Police meet regularly to do some “tough talking” with the imams at Grimhojvej, said Magnus Ranstorp, who leads the foreign fighters working group of the EU’s Radicalization Awareness Network. But Denmark has taken a notably softer approach than some European countries, with an emphasis on rehabilitating its citizens who have returned from Syria.

Aarhus is home to a lauded tip-based program that activates a network of police, social services, therapists, and community mentors to intervene with at-risk individuals. The program has been in place for decades to deal with crime and was adapted to deal specifically with radicalization in 2007. Faced with a wave of referrals, Copenhagen recently launched its own version of the program. But Ranstorp, who also heads the city’s expert group on countering violent extremists, concedes it has been understaffed and overwhelmed.

Anja Dalgaard-Nielsen, former PET executive director, who is now a director at the Royal Danish Defence College, traces the roots of the problem to a highly mobilized radical community that formed around the 2005 publication of the Muhammad cartoons in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten and the subsequent international controversy.

But rather than “organizations with a name and a phone number,” said Dalgaard-Nielsen, the greater threat is from nameless networks of charismatic recruiters, who help feed larger groups like isis.

As El-Hussein’s case shows, the pace of radicalization and the pool of potential recruits have increased dramatically with the rise of isis and its propaganda machine.

In the past, extremists didn’t want to work too closely with criminal groups that had no pretense of justifying ideology. “Old Al Qaeda, I think, was not particularly interested in highly criminal individuals,” said Dalgaard-Nielsen. “Or, for that matter, in people who suffered from mental illnesses—because they’re unpredictable, and they might do crazy things that taint your brand. But I think we have a real challenge in the sense that isis more or less has branded itself by doing crazy things.”

In recent years, a new threat profile has emerged, said Dalgaard-Nielsen: The “petty criminal” for whom ideology is often nothing more than a thin cover. Ranstorp has noticed that many European radicals today tend to be poor, poorly educated, and have long criminal records. And recruiters from extremist groups often target people who did not grow up with a grounded faith tradition.

“Many are just really losers of society who do not have a lot of religious context and experience in being able to question this issue,” Ranstorp said. “Those guys usually use the ideology to justify their violent action.” In March, a PET threat assessment warned of increasing radicalization among the criminal ranks of Denmark’s young and socially marginalized.

Social media has enabled such alienated youth to find like-minded individuals and insert themselves into an epic fantasy world, Ranstorp explained. “It’s about the end of times. This is about Judgment Day,” Ranstorp said. “This is the Super Bowl, and you’re not just invited to go to the game, you’re invited to play in it. That’s a very powerful magnet.”

Gang members make for particularly attractive recruits. They already have access to weapons and experience using them, meaning their natural barriers to using violence have already been lowered—a critical threshold along the path to radicalization.

“When people self-recruit out of these environments, the process can move very, very fast,” said Dalgaard-Nielsen.

According to a Reuters special report, an unpublished official investigation found that El-Hussein had grown increasingly religious over his final six months in prison. In September, he started to talk of heading to fight in Syria. Another inmate he’d spent time with was later discovered promoting isis on social media, via a hidden cell phone. El-Hussein grew angry at the sight of immodest clothing on television. Just before his release he assaulted another inmate “for no apparent reason.”

Prison officials added his name to a list of inmates at risk of radicalization that it flagged to PET. The intelligence service, however, was never alerted when El-Hussein was released.

Nine minutes before his first attack, El-Hussein pledged his loyalty to isis. “I swear allegiance to Abu Bakr,” the head of isis, he wrote on Facebook. He also reportedly posted a video called the “Sword of Jihad,” which featured an Arabic song, the lyrics of which state, “Our purpose is to destroy you. ... We will come to you with slaughter and death.” He listed himself as an employee of “Murder Inc.”

The March 30 issue of isis’s magazine Dabiq praised El-Hussein for his “brave” and “selfless” attack on behalf of the caliphate.

El-Hussein “did not let national borders and skies stop him. He did not let a ‘citizenship’ he disbelieved in prevent him from obeying his Lord,” it read. El-Hussein’s attack, it stated, was evidence that isis is “here to stay.”

On February 20, a crowd of 600 to 800 people turned out for El-Hussein’s funeral at a mosque on the outskirts of the capital. The large number of attendees has been interpreted as an explicit endorsement of his attack. But the more likely explanation is a combination of community support for the family, rollover from the normal Friday prayer crowd, and a smaller Salafist contingent that was, in fact, explicitly condoning El-Hussein’s actions.

Yet it was also a way to say to Danish society “up yours, we will be defiant,” said Ranstorp. “This is an anti-West sentiment that is growing. And it’s growing in our cities and our neighborhoods. How do you devise policy for that?” The Al Qaeda narrative that the West is at war (both figuratively and literally) with Islam, once a peripheral, extremist view, has now become mainstream for young Muslims raised amid the discourse of the war on terror, Abu Ghraib, and Guantánamo.

“This generational battle means the problem is much larger than a small nucleus of extremists,” he said. “It’s also about inclusion, about feeling part of the same society.”

Part of what makes finding solutions so difficult is that, arguably, life in Denmark is good for immigrants in communities like Mjølnerparken. Overall, Denmark ranks among the happiest nations in the world, and citizens benefit from a robust social safety net, which includes free health care, free university education, and other state-sponsored benefits. “It’s not a natural law that you are oppressed if you’re dark-skinned in Denmark,” said Aydin Soei, a sociologist who met El-Hussein in 2011 while researching the gangs of Mjølnerparken. “If you look at the stats, most young people from these areas and with the same family background as El-Hussein actually turn out to have good lives.”

Many gang members in Copenhagen don’t recognize their privilege, however. “Part of their identity is that they’re living in the same reality as the oppressed black man in the American ghettos,” Soei said. And this belief feeds a narrative of victimization that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy for those who never leave their insular communities.

That’s not to say that racism isn’t an issue in Denmark. There’s no doubt that landing a job interview is harder with a Muslim-sounding name on your resumé. Nagieb Khaja, a war correspondent whose parents came to Denmark from Afghanistan, said that as a young man growing up in an immigrant community on the outskirts of Copenhagen, he felt discrimination most profoundly at the nightclubs, where he often couldn’t make it past the bouncer at the door. Gangs, however, offered power and prestige. “When I went out with the gangsters, we didn’t have to stand in the queue. We were treated like kings,” he said. “It was a totally different world.” Many of his friends from those days became either gangsters or social workers. Today, he said, kids from these communities are increasingly becoming Islamists—in the post–September 11 world, the most provocative way to reject the society from which one feels alienated.

The public response to the shooting has not helped alleviate that sense of antagonism. In February, polling data showed that half of Danes want to curb the number of Muslims allowed to live in Denmark. The anti-immigrant Danish People’s Party received a surge of support, finishing second in June elections. A new center-right government announced it would cut immigrants’ benefits and strengthen border controls. Today the party’s founder, Pia Kjærsgaard, who was once named “racist of the year” by a Swedish magazine, is now speaker of Parliament.

El-Hussein’s milieu is a subculture that defines itself in opposition. “They have an enormous hatred toward society, and the hatred also has to do with the identity of being a religious minority,” said Soei.

That doesn’t mean that places like Mjølnerparken are hotbeds of potential terrorists. Not all disaffected young men pick up an assault rifle and gun down innocent people. In the aftermath of the attack, a spokesman for the Brothas publicly disavowed El-Hussein’s actions. And Soei said his contacts in the gang told him that El-Hussein had been kicked out earlier because he was too violent and couldn’t be controlled.

Still, the parallels between the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris and El-Hussein’s, between the profiles of the attackers and so many of the gang members Soei has interviewed over the years, are striking.

“If I were a lawmaker, a politician in another European country with the same problems as we have in Denmark and in Paris, I would be concerned,” Soei said. “The feeling of not belonging, the feeling of society being against you, of you being against society … isn’t a Danish problem or a French problem. It’s a common European problem.”

Several weeks after my initial visit to Mjølnerparken, I sat down again with Ahmed and Abdurramadan, along with two of their friends, Abdi and Salahedin. Like young people the world over, they were at various moments outspoken and ambivalent as they sought to articulate their worldview. They were critical of Israel and expressed support for Palestine. They supported the principle of an Islamic caliphate. Yet they were also bothered by the atrocities committed by isis—killing children, beheading hostages. That was not their conception of Islam.

Not that they were devout, learned Muslims. “I’m not practicing so much,” Salahedin admitted. “But I’m reading a little bit. Not the Koran because I don’t read Arabic.” He was absorbing YouTube clips, isis propaganda, and occasional sermons at the mosque, though. “I’m just checking everything out.”

What they agreed on was that, if the status quo persists, the next generation will be all the more violent.

Omar El-Hussein’s actions were the product of a combustible nature and a discourse that paints all Muslims as fanatics.

“He felt like the world looked down on Muslims. And they kinda do,” said Abdi. “If you keep telling that guy, ‘You a terrorist, you a terrorist’—on the television, everywhere you look—at the end, he’s gonna think, ‘I’m a terrorist.’”