No one knows what the Prophet Muhammad looks like. From historical sources, we can reasonably surmise he was an Arab male, but that’s such a broad category as to say almost nothing about his physical features. For that matter, we don’t really know anything about the real faces of Moses or Jesus, although in both cases over the centuries artistic conventions have codified fictional rules about their appearance. There are fewer such iconic conventions for Muhammad, in large part because of the prohibition of some sects of Islam against depictions of the Prophet.

These prohibitions have all sorts of curious side effects, far beyond the well-known violence visited upon various artists who have tried to depict Muhammad. Because there is no standard iconic rules for depicting the Prophet, an image of Muhammad is always a curious act of will: Often we only know that the Prophet is being rendered because there is some label or title affixed to the image. A cartoon of Muhammad plays the same sort of mind games as René Magritte’s famous painting “The Treachery of Images” (1928-29) where the statement “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” is affixed under an image of a pipe.

Art Spiegelman’s comic strip commentary on the Charlie Hebdo controversy, “Notes from a First Amendment Fundamentalist,” delves deeply into these issues. In the cartoon, Spiegelman (limning himself in his stylized rodent form, developed for his graphic novel Maus) is holding two magazine covers (images within an image). One, titled "No Problem," features a standard smiley face and says, “Have a nice day.” The other, titled "Problem!," features the same smiley face wearing a turban and identified as “Mohammad.” As the contrasting images show, it takes just a few squiggles and a label to turn a smiley face into a blasphemous provocation. The offense isn’t so much in the image as in the intent. To say you are drawing the Prophet is the scandal, more than what is drawn. A drawing of Muhammad is an idea or an assertion more than it is a physical thing.

“So many Muslims who never saw or needed to see the cartoons died in the international riots developing out of the Jyllands-Posten’s first provocations,” Spiegelman notes in an email, referring to the Danish newspaper whose publication of Muhammad cartoons in 2005 sparked deadly protests throughout Europe and the Muslim world. “Intent to defame was enough to cause the frenzy.” Spiegelman also notes that it is more accurate to say "a ban on intent as well as images."

Spiegelman’s strip ran in many publications, including The Nation in the United States and Le Monde in France. Spiegelman offered the strip to Britain's The New Statesman, which has a content-sharing agreement with The New Republic, but they chose not to run it. Spiegelman argues that this is because the magazine has a blanket policy of not printing images of Muhammad. The New Statesman says they never had plans to run the strip and Spiegelman’s belief that the magazine had agreed to run it and then chickened out was due to “poor communications.”

Whatever the facts of The New Statesman case, it’s undeniable that many supposedly secular publications in the West and elsewhere do adhere by the prohibition against depicting the Prophet. The New Republic does not have a blanket policy, but generally avoids publishing depictions of Muhammad. The New York Times and many other newspapers refused to run the Charlie Hebdo depictions of Muhammad despite their importance in helping to understand an important news story.

Adherence to a rule that Muhammad should not be depicted is a very curious thing. Abiding by the prohibition can’t be an act of belief, since these publications aren’t run by Muslims who believe the prohibition is crucial to their faith (and in any case these publications have a secular mission and identity). Nor can the prohibition be just about displaying sensitivity to Muslim sensibilities since there is no consensus among Muslims that the prohibition should be adhered to or is binding among non-believers. In fact, certain strands of Islam, notably those in Iran, have a rich history of depicting the Prophet. A thorough prohibition on depicting Muhammad would, if followed by all, mean the banning of a rich vein of Islamic art.

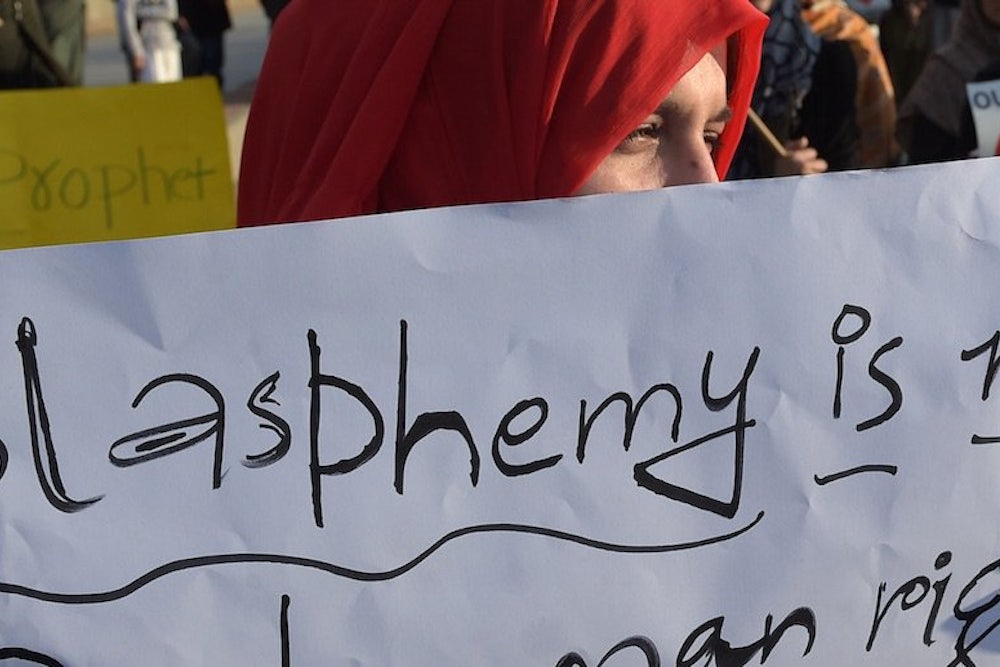

To some believers, drawing the Prophet is an act of blasphemy. And historically, blasphemy laws have covered both believers and unbelievers: It is the act insulting a sacred figure that is blasphemous, whether or not the person making the insult believes or not. But the shrewd Catholic intellectual G.K. Chesterton once observed that for insults to truly be meaningful, blasphemy has to spring from a place of belief. “Blasphemy is an artistic effect, because blasphemy depends upon a philosophical conviction,” Chesterton argued in his 1905 book, Heretics. “Blasphemy depends upon belief and is fading with it. If anyone doubts this, let him sit down seriously and try to think blasphemous thoughts about Thor. I think his family will find him at the end of the day in a state of some exhaustion.”

Chesterton's comments were focused not on blasphemy as a binding legal and cultural prohibition, but on the subjective experience. Still, they do serve to show that the current battles over depicting Muhammad are more about creating tribal loyalties than religious belief.

The controversial cartoon images found in Jyllands-Posten or Charlie Hebdo have a very different impetus than traditional blasphemy. The great works of blasphemous art were created by either believers or those who grew up in the shadow of faith. The delicious mockery of Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) wouldn’t exist if the comedians hadn’t grown up in a Christian culture. Andres Serrano’s "Piss Christ" (1987), a photograph showing a crucifix immerse in Serrano’s urine, gains much of its power from the fact that the artist is a Christian. The fact that Salman Rushdie was raised as a Muslim gives his novel The Satanic Verses (1988) a sharper and precise bite, something lacking in the often generic cartoons of cartoons of Muhammad created by those outside the emotional orbit of Islam.

If true blasphemy requires faith on some level, then secular blasphemy is a contradiction in terms. To try and blaspheme someone else’s God or Prophet, figures who exist as no more real to you than Zeus or Thor, is a strangely shallow activity. You can offend others but you are not staking a personal gamble in damnation, the sort of defiance that gives energy to the work of, say, James Joyce or André Gide.

To the cartoonists who drew the images for Jyllands-Posten or Charlie Hebdo, Muhammad already existed as an abstraction before they picked up their pens. To unbelievers in the secular west, Muhammad exists on the same plane as Santa Claus, Don Quixote, or Ronald McDonald: a logo or emblem of an idea. The mockery of the cartoonists was aimed not at Muhammad the Prophet, who was already unreal to them, but rather Muhammad the logo, the emblem of Islam as a religion.

The believing Muslims who took offense at the cartoons were often motivated by their conviction that Muhammad isn’t a logo but a real person, as much an actuality as any member of their family. But even on the Islamic side of the controversy, there was certainly a tendency to treat Muhammad as an abstraction. Given how calculated and strategic the violence directed against Charlie Hebdo was, with its clever intent to polarize European opinion, Al Qaeda was treating Muhammad as a flag who has been captured by the enemy and needs to be regained. But to use the Prophet as a tribal avatar is really no different than making him into a cartoon. On both sides of the cultural divide, Muhammad exists more as a marker to quarrel over than a person or messenger.

The battles over cartoons of Muhammad is really a struggle between competing abstractions. Unfortunately, the blood that is shed is real.