Florida will always conjure a sense of dread for a certain generation of Democrats. After its hanging chads infamously decided the 2000 presidential race in George W. Bush’s favor, the state has now voted very narrowly for Barack Obama in two presidential elections, the first time the state has gone Democratic back-to-back since it voted for Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman in 1944 and 1948. But beyond just the presidency, the demographic trends in Florida suggest a state that Democrats should, put simply, own. In 2000, 65 percent of the state’s population were non-Hispanic whites. As its Hispanic population has grown, that figure has now fallen to 56 percent. And unlike earlier generations of Cuban Floridians, the majority of whom voted for Bush, the Sunshine State’s new Hispanics tend to lean Democratic. The future may be unpredictable, but the state is unlikely to get less Hispanic any time soon, and neither is the rest of the country. That’s why many Democrats believe that they will be in political control of a country that census data projects to be majority-minority by 2043.

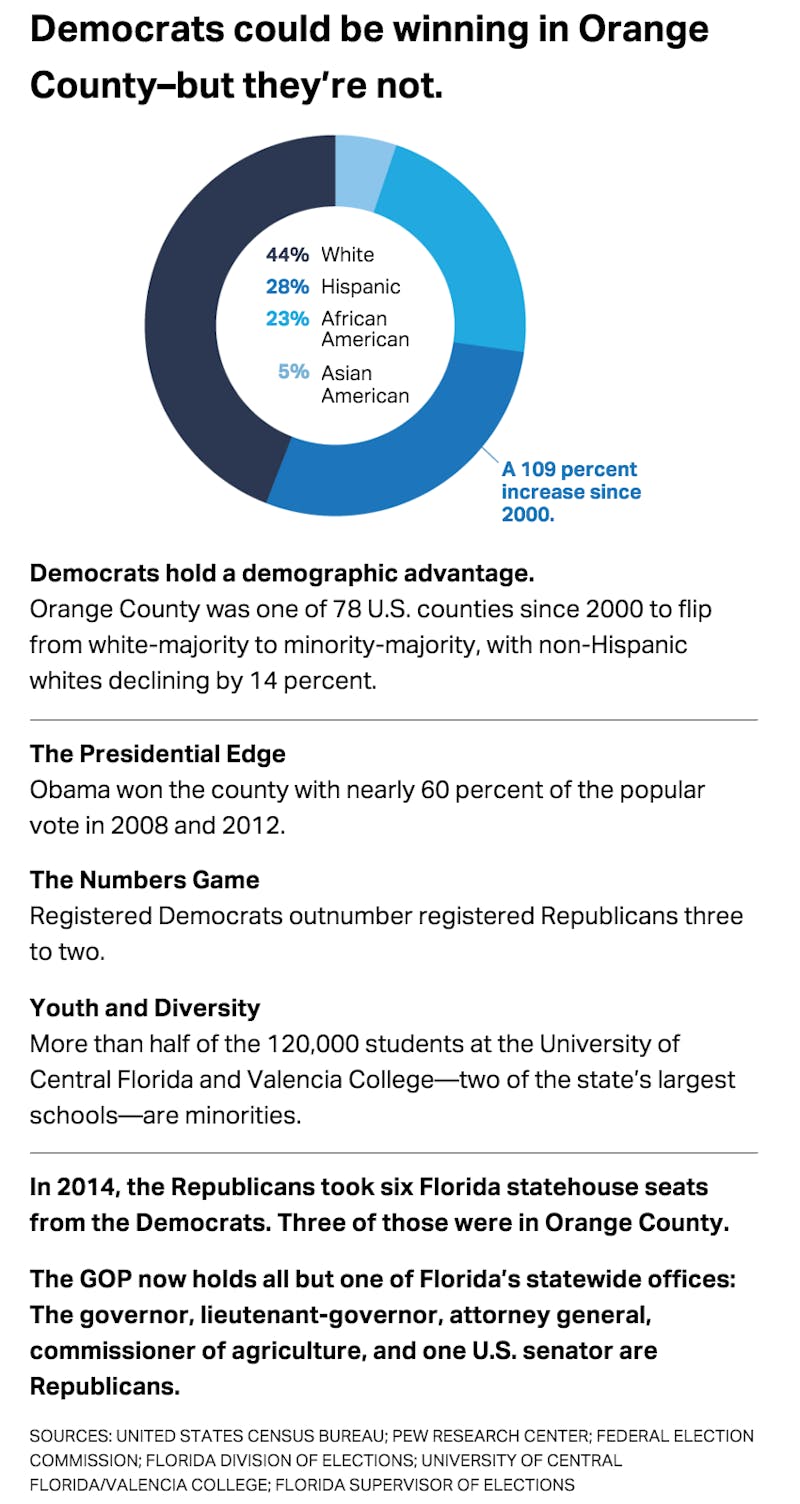

But demographics are not destiny. Consider Florida’s most prized political territory: the Interstate 4 corridor, which runs from Tampa to Daytona Beach and straight through Disney World. This region happens to be the hub of a Hispanic population boom. Obama won Orlando’s Orange County, which has a population that is 28 percent Hispanic, 23 percent African American, and 44 percent non-Hispanic white, by nearly 20 points in both 2008 and 2012. Registered Democrats in the county now outnumber registered Republicans by three to two. Yet in down-ballot races, the area is hardly safe for Democrats: In the 2014 elections, Republicans picked up six statehouse seats from Democrats; three of them were in Orange County.

The biggest upset was the defeat of Democratic incumbent Joe Saunders, who lost his 49th district seat by only 714 votes to Rene Plasencia. The district is full of college students who might be expected to champion the 31-year-old Saunders, who is openly gay. But Plasencia, a half-Cuban and half-Puerto Rican former high school track coach, played up his Hispanic heritage and recruited former students to volunteer for the campaign to send “Coach P” to Tallahassee. Local Democrats simply weren’t prepared for the strength of Plasencia’s campaign. “Frankly they were people who underestimated the race,” said Steve Schale, a Florida Democratic consultant who directed Obama’s 2008 campaign in the state. “That’s the seat that I don’t think we should have lost.”

Obama’s electoral victories in 2008 and 2012 seemed to herald a new era of Democratic dominance built on a winning coalition of young and minority voters, one that would indicate a long-term, structural advantage for Democrats. It seemed to be the scenario John Judis and Ruy Teixeira famously predicted in 2002, at the nadir of Democratic influence during the Bush administration, in their book The Emerging Democratic Majority. Increasing urbanization, education, and racial diversity offered “fertile ground for the Democrats’ progressive centrism and postindustrial values.” A few days after the 2012 election, Teixeira, writing for The Atlantic, pointed to Obama’s success with minority voters over Mitt Romney (80 percent to 18 percent); with educated professionals (55 percent to 42 percent); and among young voters (60 percent to 37 percent). He reminded readers that Obama was “the first Democratic president since Franklin Roosevelt to win successive elections with more than 50 percent of the vote, powered by the continuing rise of the coalition described in the book.” As Teixeira recently told me, while Democrats must be mindful of not continuing to hemorrhage white voters, “the advantages, all else equal, continue to increase.”

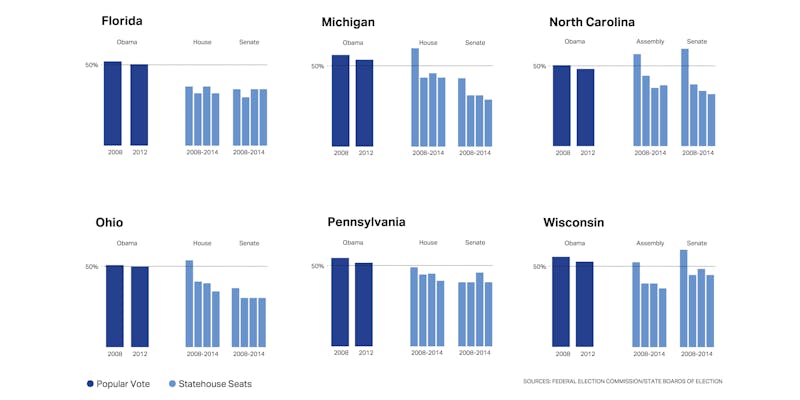

But set Obama’s impressive electoral victories aside and the Democrats look less like an emerging majority and more like a party in free fall: Since Obama was sworn in six years ago, Democrats have suffered net losses of 11 governorships, 30 statehouse chambers, more than 900 statehouse seats, and have lost control of both houses of the U.S. Congress. After the 2014 midterm rout, Democratic strategist Simon Rosenberg penned a memo deeming it “remarkable”—an understatement—that voters had given Republicans so much control so soon after giving Democrats Rooseveltian wins nationally. The implications, Rosenberg warned, were dire: “The scale of Republican success in recent years outside the Presidency has altered the balance between the two parties now, and may even leave the GOP a stronger national party than the Democrats over the next decade.”

That has been the experience in Florida. Since 2008, the GOP has solidified its control of the Sunshine State. Republicans now hold every statewide office in Florida except for the Senate seat of Bill Nelson, a former astronaut who was first elected to Congress in 1979. In the statehouse, Republicans command a supermajority, which they used to create a redistricting map so heavily weighted in their favor—one congressional district was so convoluted it resembled a snake—that they were forced by a county court in 2014 to redraw it. And it’s all happened in the home of Representative Debbie Wasserman Schultz, chair of the Democratic National Committee.

Florida reveals the existential challenges the Democrats confront. The emerging Democratic majority may be an opportunity that Obama turned into reality. But unless Democrats find better ways to turn out their new voters—and win back more of the white voters flocking to the GOP—the party will continue to lose ground in Congress, governors’ mansions, and statehouses across the country—regardless of who wins the White House in 2016. To do that, Democrats will need better ways to organize their traditional party apparatus—or find new ways to leverage outside groups and spending to strengthen their ties with new voters before Republicans do. “Our party has a problem,” Wasserman Schultz said in a post-midterm “autopsy” video. “We’ve got to do better.”

In 1999, when Anthony Suarez was elected to the Florida statehouse, he was the first Hispanic state legislator to win in central Florida, the second Puerto Rican ever to do so in the state—and a Democrat.

“Now we are six,” he said, as he addressed a panel of sitting Hispanic state legislators attending “Political Salsa,” a forum he’d organized in Orlando in late May. But not all of his colleagues are Democrats. Three are Republican, including two freshmen who unseated white Democratic incumbents in 2014. Former State Representative Suarez also switched to the Republican party in 2001 because of his right-leaning views on abortion and other social issues. Suarez introduced one of the freshmen as Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A” played in the background: “Born in Orlando, Florida,” he cried. “A real ‘Mickey Rican’: Republican Rene Plasencia!”

Republican and Democratic activists watched as local media personalities peppered the legislators with policy questions. The Democrats even got to their feet as the debate turned to Medicaid expansion, which Florida’s House Republicans were blocking. But while the event was bipartisan, the state Republican Party had chipped in more financial support than its Democratic counterpart. At the reception afterward, more attendees took selfies with the cardboard cutout of Reagan than with the one of Obama. I spoke with a 39-year-old Hispanic lawyer and Republican voter named Carlos Meléndez about the best message to send a disengaged electorate. “Decisions are made by those who show up,” he said.

After the GOP’s presidential defeat in 2008, the Republican Party’s top donors and strategists found a new cause to rally behind: winning on the state level. For the past five years, conservative money men like the Koch brothers have poured tens of millions of dollars into a concerted effort to flip statehouses, win governors races, and turn purple states red. Last year, the Republican State Leadership Committee raised $38 million, compared with its Democratic counterpart, which took in just $16 million; the Republican Governors Association raised nearly $50 million more than the Democrats. And Republicans have turned this state-level money into state-level election victories, favorable demographic trends or no.

Democratic donors, meanwhile, have preferred to focus on issues and policy reform with broad left-wing support, like climate change and gay marriage. Some have taken cues from the Kochs and targeted state legislative seats to advance causes—in Minnesota in 2012, Tim Gill helped fund a successful effort to regain the governorship and the statehouse, which ultimately paved the way for the state to legalize gay marriage a year later. But that has been more the exception than the norm for Democratic spending. “Donors weren’t guided in that direction,” Democratic consultant Joe Trippi, Howard Dean’s former campaign manager, told me. “It’s just been a much, much lower priority.”

The disconnect between Democratic success nationally and locally is also partly due to the kind of “post-partisan” candidate Obama sought to be in 2008. Obama’s young, racially diverse base flocked to him precisely because he promised to transcend both parties. Out of necessity—at the time, much of the party establishment was firmly committed to Hillary Clinton—Obama circumvented the traditional party infrastructure with volunteers and small donors that were more loyal to him personally than to his party. In places where there was an entrenched Democratic machine, like Philadelphia, the campaign famously refused to hand out “walking around money,” cash payments that go to entrenched operatives and party loyalists in exchange for turning out the vote.

The power of local Democratic Party organizations has generally been in decline for decades, and state and local parties haven’t always proven to be the best stewards of their candidates’ interests, either. Local machines rely heavily on volunteer labor and vary widely in quality: Some have been torn apart by leadership fights and scandals; others are still run by old power brokers who’ve clung to outmoded organizing strategies. Howard Dean’s turn as DNC chairman included a vow to revive party leadership through a “50 state strategy,” which didn’t succeed, and even local party leaders didn’t always blame Obama for circumventing them. One Florida Democrat whom I spoke with, who declined to be named because he is still active in local politics, said the Obama campaign in both 2008 and 2012 was wise to avoid meaningful relationships with the local Democratic executive committees: “Too many of them are train wrecks.”

But it’s become increasingly unclear what the official party’s role should be at any level now that digital organizing has allowed individual candidates, and increasingly outside groups, to access voters directly. Party building has become even more uncertain since the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, which allowed corporations and unions to spend unlimited amounts on ads and other expenditures, further diminishing the role of political parties. In fact, entities like super PACs are legally barred from coordinating directly with candidates and the campaigns. “You don’t have to go to the political parties anymore—you can pack your tent within any camp,” said Donna Brazile, a veteran political strategist and DNC vice chair.

So while Obama may have, to an extent, reinvented campaigning, bringing together a new coalition that delivered the biggest Democratic presidential victory in decades, he didn’t reinvent the Democratic Party. Instead, he created an independent campaign structure that could win elections by driving the strategy, fundraising, and organizing itself. In 2012, he did integrate the state parties into his campaign and directed some of his funds through them. Ultimately, though, it was still Obama in control, not the party.

The Republican National Committee, in contrast, played a central role—much criticized in campaign autopsies—in organizing for both John McCain and Mitt Romney. But what seemed to be a weakness in presidential strategy has turned out to be a strength in the off years. “When a party holds the White House, the opposing party often gets smarter and better about doing things in terms of developing a bench and focusing more on the local level and state level,” said Liz Mair, a Republican strategist and former RNC staffer.

Republicans, meanwhile, haven’t discounted the threat that the new Democratic coalition poses to their long-term political prospects. In Florida and elsewhere, Republicans have increased their share of the white vote, which has given them a particular edge in the midterms when younger and minority voters are more likely to stay at home. But given the shrinking share of white, noncollege educated voters nationally, Republicans will either need to expand their share of the white vote even further or, more probably, win over larger numbers of younger and minority voters to prevail. “Doubling down on white voters does not look like a very promising approach to restoring the White House to GOP control,” Teixeira wrote in a 2013 Sabato’s Crystal Ball article he co-wrote with Alan Abramowitz. Republicans have more of an opportunity in this regard than Democrats might like to believe, as racial categories and self-identification tend to evolve: There’s a long history of immigrant groups becoming assimilated into white America; Hispanics of today could become the Irish- or Italian-Americans of the past, and their political views could shift accordingly. (Judis, meanwhile, recently recanted part of his book by arguing that Republicans could gain a lasting advantage by targeting middle-income voters across racial groups.)

Obama’s senior leadership made some effort to institutionalize the success of his campaign by turning its grassroots structure into a permanent nonprofit, Organizing for Action—an unprecedented move for a sitting president. But Organizing for Action has focused on supporting Obama’s agenda, not electing other Democrats. “They have maintained their solid support of the president without becoming another caucus within the party—he has a separate apparatus out there,” Brazile said.

Some Obama partisans have argued that the president’s supporters have a special affinity for him and not the party, and that other Democrats can and have benefited from his success. “I would point to the actual results of Democrats in very red places in 2008 and 2012. Look at how they did,” said Mitch Stewart, an Obama campaign veteran. But that still leaves Democrats with the problem of how to succeed when Obama, or someone similarly popular, isn’t on the top of the ticket.

Carlos Guillermo Smith, 34, never planned a life in politics. “I really am kind of an accidental person in this process,” he said, reflecting on his transition from a supervolunteer to his first job in the Florida statehouse. As with millions of others, his political awakening occurred during Obama’s 2008 campaign: A manager at a Men’s Wearhouse when he signed up to volunteer, he had never before been seriously involved in organized politics. Today his two-level condo is a virtual homage to the president, covered in photos from the trail. A giant portrait of Obama sits at the bottom of his stairwell, with “DESTINY” written across the bottom.

Unlike most Obama supporters of his generation, Smith became a Democratic partisan, going straight from volunteering for the presidential campaign to volunteering for congressional races and, ultimately, staff positions. “I have a very, very strong identification with the Democratic Party,” said Smith.

But in the I-4 corridor, Smith is an outlier. Many of the new voters are recent arrivals from Puerto Rico, who are more likely to be politically unaffiliated. “We’ve grown so fast so quickly—we don’t have a long history of well-established Hispanic community organizations,” said Jose Fernandez, former chief of staff to Orlando’s mayor. Plasencia and Bob Cortes—another Republican newcomer to the state legislature—prevailed in 2014, despite being outspent by the Democratic opposition in Orange County, because they focused on Spanish-language media and community outreach. In their campaigns, both made a point to attend the Orlando Puerto Rican parade, which was organized by Plasencia’s father, a Cuban-American event producer. According to the state Republican party, it was the first time in six years that someone representing the Florida GOP had shown up.

The Saunders upset was a personal loss for Smith as well: He was Saunders’s chief of staff in the statehouse. “People were sharpening the pitchforks to come after me, blaming the party leadership for some of these failures,” Smith, now chair of the Orange County Democrats, recalled. He defended the local party’s role in 2014, arguing that local activists came out to help knock on doors for Saunders, even as the statewide leaders focused elsewhere. Now he’s looking to recruit more Hispanic candidates to reclaim the seats lost to Republicans in the midterms, and after Plasencia recently opted to run in a more GOP-leaning district, Smith declared his own candidacy in his old boss’s 49th district. “When your job is to recruit people to run for office, sometimes you look in the mirror, and you don’t have to go too far,” he said.

Down-ballot losses can have a negative impact up the chain as well. When state and local-level candidates lose, it cuts off the supply of new talent for higher office, leaving the national party with a short list of old, familiar faces. That process left Florida Democrats with Charlie Crist, the former governor who went from Republican to Independent to Democrat, as their 2014 gubernatorial candidate, in large part because no one else who was willing to run was remotely viable. “After Charlie, what? After Charlie, who’s their great hope? If they don’t win with Charlie Crist, it has to be stunt casting because their bench is so weak,” GOP strategist Rick Wilson joked last year in an interview with NPR affiliate WUSF. It wasn’t just a partisan jab: Crist, who lacked, to put it mildly, strong ties to the party, lost to Republican incumbent Rick Scott, one of the least popular governors in the country.

That disparity is on display in Florida’s 2016 open-seat Senate race, which is open only because its current holder, Marco Rubio, emerged as one of the top contenders for president and is not running for re-election. The Democratic frontrunner is, like Crist, another GOP refugee: Patrick Murphy, who until 2011 was a registered Republican, but was elected to Congress as a Democrat in 2012. The party’s paucity of formidable statewide candidates “didn’t happen overnight,” said Scott Arceneaux, executive director of the Florida Democratic Party, pointing out that Republicans have controlled the statehouse for nearly 20 years. “You got a whole generation of folks who weren’t locally elected to office . . . the result is that our bench is a lot shorter than theirs.” The problem is evident at the presidential level as well: Hillary Clinton faces thin opposition while the Republican field is so crowded that TV networks have to limit the number who will participate in the main debates to ten. The function of any party, Joe Trippi told me, is to develop winning candidates. “Go local, go small, put a lot of energy into recruiting and finding people,” Trippi said. “Because later on, they are the people who are going to be able to get $20 million contributed online.”

As an example, Florida Democrats point to first-term Representative Gwen Graham, who was one of only two House Democrats in the country to unseat a Republican incumbent in 2014. The daughter of Bob Graham, who is still popular in Florida as a former senator and governor, she won by running as a moderate who could connect with the white Southern voters of Florida’s Panhandle and frequently invoked her father’s legacy. Or, as Smith put it to me, “Recruit candidates that look like their district.”

In central Florida that means finding Hispanic candidates to run. When Clifford Davy and Michelle Stile, two local Democratic activists, took over the Young Democrats in Orange County this past March, they realized how weak the political infrastructure had become. “There wasn’t an actual structure at all,” Davy told me. And there easily could be: Orange County is home to the University of Central Florida (UCF) and Valencia College, one of Florida’s largest community colleges, which have a combined enrollment of 120,000 students. Minorities make up more than 40 percent of UCF’s student body and 60 percent of Valencia’s. Large schools such as these can be a major resource for future Democratic voters, volunteers, staffers, and candidates. Obama’s campaigns tapped into these pools of enthusiastic young people, but local Democrats have not, Davy told me. “We didn’t have any chapters at these large institutions,” he said. There is a Young Democrats group at UCF, but participation remains negligible. “UCF is, what, like, 60,000 kids?” said Davy. Stiles nodded: “And we’ve got ten people who show up.”

The ultimate hope of any of these groups is to build relationships with voters that don’t rely on the charisma of an individual candidate. That’s what the old political machines used to do: Organize the base, even when the national spotlight was elsewhere. Such organizing efforts are particularly important in places like central Florida, which has a high concentration of voters with no longstanding ties to either party and who aren’t used to voting as often. Puerto Rico holds general elections only once every four years, and participation rates are extraordinarily high. Puerto Ricans in U.S. elections, however, tend not to turnout in such large numbers. Osceola County, just south of Orlando, had the third-lowest voter turnout in the state in 2014; Orange County was the fourth-lowest. No one is calling for a return to the old patronage model, but something—anything—has to replace it if Democrats want to perform in elections as the demographic trends suggest they should.

For activists like Davy and Stile, who have both organized for Obama, it’s about relationships on the ground. “The basis of organizing is creating a personal connection with someone you want to reach,” Davy said. Treat voters as individuals: Make sure that neighbors canvass their own blocks, for example, or identify targets using data that are more finely grained than just membership in a demographic group. “The Democrats go after minorities, but sometimes they’re not as sensitive to the individuality of the minority community,” said Davy, who is African American. “People don’t take the time, and they don’t spend any money to find out what Cliff wants, how he feels—everything about me. They’re more like, ‘He looks this way, he’s probably going to vote this way, so move it along, put him in a big bunch with everybody else.’”

That way of thinking is more in keeping with public relations campaigns than grassroots ones. Democratic Party committees, said Obama campaign veteran Schale, “have become communications machines, and they’ve gotten away from being organizing machines.” Democrats have suffered from the decline of their most reliable organized ally, labor unions, and the newer movement activism that has recently animated progressives—Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter—has not filled the vacuum. The Tea Party movement, by contrast, has found ways to focus its anti-government message on state and local elections—so much so that it has essentially been subsumed by the Republican Party, which has maintained steady support from old-line stalwarts like Chambers of Commerce and religious organizations.

The modern Democratic Party has long prided itself on being a big tent that can include competing interests and priorities. What’s striking is that the party’s struggle to organize is happening at a time when Democrats are actually more ideologically unified than they have been in decades, in part because the down-ballot losses have pushed out more centrist members. I spoke with a Democratic activist named Patty Duffy at an event held just outside Orlando by Equality Florida, the LGBT rights organization that Smith works for. She told me she was overjoyed when the state’s gay marriage ban was defeated in January; she married her partner in a beach ceremony a few months later. She worried, however, about whether Democrats will ever care as much about organizing as a party as much as they do about their individual causes. “We’re all in different directions,” Duffy said, sitting next to her wife. “Who can we get to bring us together?”

After the 2014 elections, the Democratic Party leadership launched a flurry of task forces and commissions, designed to rebuild the party and analyze, in the words of one report, “the devastating losses at all levels of government” that it had suffered since 2008. The party has made new promises to organize and invest down-ballot: A DNC task force recommended “working with state parties to build partnership agreements that include training, evaluation, metrics, and incentives,” as well as creating a “three-cycle” plan to focus on redistricting. Likewise, the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee committed $70 million to a redistricting program called “Advantage 2020,” with its main strategy being to win statehouse races in the lead-up to the next reapportionment.

Wasserman Schultz denied, however, that these initiatives mean the DNC has neglected state parties, calling the latest efforts “an enhancement to our ongoing commitment to the 50 State Strategy” that began under Dean. She said that more down-ballot races will have access to the data-driven tools that powered Obama’s campaigns. “I would dispute the notion that we aren’t building on the amazing organization we have had in the past two presidential years.”

She deflects blame for the decrease in turnout to Republicans. “Part of the reason that voting by certain constituencies who are traditionally Democratic-leaning—including Hispanics, younger voters, women, and people of color—has been depressed is because they have been specifically targeted by Republican attacks on voting,” she said. “Policies such as restrictive voter ID laws disproportionately hurt these groups and make it harder for them to vote.”

Outside donors on the left have also finally begun to pay attention to the party’s down-ballot woes—and the threat of major Republican outside spending on the state and local level. Democracy Alliance, a network of wealthy liberal donors, committed in April to raise more than $150 million over five years to strengthen Democrats on the state level. But their plan—“2020 Vision”—will give support to groups that focus on specific policy issues, like inequality or climate change. So it’s unclear how much will directly go to funding state legislative races—or, that is, to actually electing Democrats.

But the DNC hasn’t yet released its full autopsy report from the 2014 election, while the next presidential race is already looming. And that’s part of the problem. “The DNC has so much pressure put upon it to be where all the money is raised, and all the resources go to the presidential candidates and the presidential campaigns and state parties during presidential campaigns; it’s been really tough for them to look beyond four year cycles,” said Maria Cardona, a Democratic political strategist.

Democrats see an opportunity, however, for Hillary Clinton to bring the two together. Clinton’s greatest strength as a candidate—and her greatest weakness—is that she is the face of the Democratic establishment, a consummate political insider whose base resides within the party in a way Obama’s never did. “Hillary is all about building up the Democratic Party,” Susan Johnson, a Clinton organizer in Virginia, told a roomful of supporters at a gathering in May. “What she wants to do is to make sure that all our local candidates get elected.”

One way that she’s making that happen is by helping them fill their own coffers. At her first campaign stop in Virginia, Clinton is scheduled to headline the Jefferson-Jackson dinner—the state party’s big annual fundraiser; she’s making similar visits in Iowa, New Hampshire, and Arkansas. Obama attended some of the same events during the 2008 primaries, when he was competing with Clinton for Democratic support. But given Clinton’s huge lead in this cycle’s Democratic Party, the emphasis has shifted: Outside of the earliest primary states, it’s less about what she can get from state Democrats than what they hope to get from her. “Hillary Clinton is committed to strengthening Democratic Parties and helping them win elections across the board this year and beyond,” said Tyrone Gayle, a campaign spokesman.

Obama made similar promises after he had secured the nomination. “We’re building lasting infrastructure which will not only help us win in November but build the progressive movement for years to come,” he said in the lead-up to the 2008 election. State and local party committees are betting they’ll play a more central role this time around. But the ultimate priority of any presidential campaign will always be on winning the White House. “We didn’t have time to train up a [Democratic executive committee] chair that thought we should be doing 27 kinds of buttons to give out at county fairs,” said Schale. “It’s not really the job of the presidential campaign to strengthen local parties—that’s the job of the state party.”

That’s why some state Democrats are already thinking ahead to 2018. The Ohio Democratic Party has embraced what it’s dubbed a “1618 strategy” to avoid another boom-bust cycle after the presidential election by getting supporters to think about the next midterm election while also gearing up for 2016. The Florida Democratic Party has unveiled a similar plan, one that will train and develop candidates for local races, as well as integrate activists more closely into the party.

During my time in Florida, I met a group of Hispanic men and women who were taking classes in medical billing at a vocational school. None of them strongly self-identified as Democrats, although listening to their political views—disdain for Rick Scott, a desire for strong labor laws to protect workers—they sounded like low-hanging fruit for party outreach. I asked them if they could name a local Democrat who they thought had done something good for central Florida. At first they couldn’t.

“What’s his name—the mayor in Orlando?” one of the women finally said, but her classmates were unable to come up with a name.

“Siri, who’s the mayor of Orlando?” one of them asked her iPhone.

No response.

“Who’s the mayor of Orlando, Florida?” she repeated. The results came up on the screen a few seconds later. “Dyer,” one of the women said. “Buddy Dyer.” He’s a Democrat.