Before a roaring crowd, a young community organizer from Chicago took the stage to lay out his vision, having unseated a long-standing incumbent in an upset victory earlier this year.

“I don't work for the corporations. I don't work for the rich. I work for the people and our agenda!” Carlos Ramirez-Rosa told a roomful of activists in Washington, D.C., who listened as the 26-year-old explained how he became the first gay Latino elected to the Chicago city council.

It was the week that populism meant as little as Hillary Clinton eating a Chipotle burrito. But hundreds of miles from Iowa, at a hotel in northwest D.C., progressive activists were trying to hammer out their own agenda for “everyday people”—one that would go beyond the fading pipe dream of having Senator Elizabeth Warren run for president. “In many ways people are ready for Warren, but they’re not waiting anymore,” said George Goehl, executive director of National People’s Action (NPA) and National People's Action Campaign, which brought progressive activists from around the country for a mid-April conference dubbed “Populism2015.”

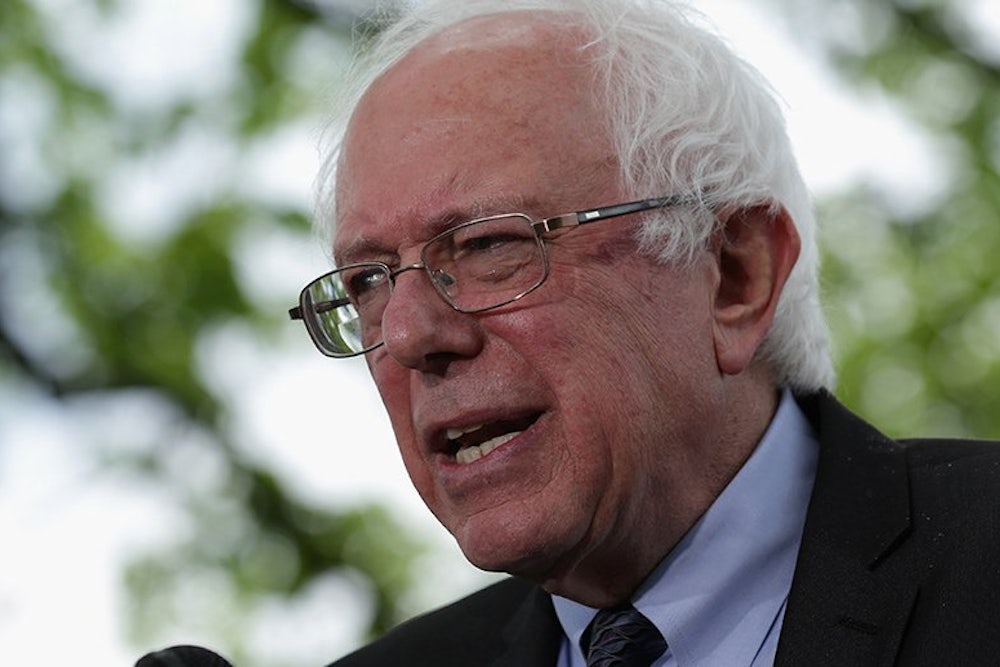

Another progressive icon has since jumped into the Democratic primary. But while the left hopes that Senator Bernie Sanders can be an effective foil to Clinton, few expect the 73-year-old Democratic Socialist to win. Instead, some key groups are cultivating the next generation of leaders to carry the progressive torch—a project that requires diving into the ugly world of campaign politics in a way the left has often been loath to do.

To that end, NPA’s members, allies, and affiliates are trying to recruit candidates from their own ranks to run for down-ballot offices across the country: city council, state legislature, the public utility commission. For the organizers of Populism2015, it’s the most natural bridge to electoral politics from the mass protests that have been the most galvanizing force on the left in recent years, like the “Fight for $15” to raise the minimum wage and the Black Lives Matter protests that have spread since Ferguson.

“The case for going local is strong. D.C. is broken, but progressive policies can and are being won in cities and states across the country,” said Branden Snyder, Detroit organizing director for Michigan United, a group that’s part of NPA’s coalition. “We can change the nation by organizing hundreds of our members to run for office. We can open up and expand the electoral map.”

Ramirez-Rosa has become an early poster child for the effort and a reminder of just how far a community organizer from Chicago can go. “In order to elect national leaders, we need a local bench of progressive leaders,” he said. “Conservatives have done a much better job at developing young leaders and having them run for office and moving up the ranks. Progressives have some catching up to do.”

National Democrats have become painfully aware of the left’s pipeline problem, and not just because of the party’s thin 2016 bench. “There has been a significant erosion of the party’s position in everything below the presidency in Congress and statehouses,” said NDN President Simon Rosenberg. Republicans “have an enormously strong 40-something generation that has to be defeated by Democrats over the next ten years at the state and local level,” he added.

For the progressive left, the problem isn’t simply that Warren is unlikely to run for president, or that Sanders is unlikely to win; it’s that they won’t have more Warrens or Bernies in the pipeline either. Three of 2016’s most prominent candidates—Senator Marco Rubio, Governor Scott Walker, and Senator Ted Cruz—are all in their forties and rose up through their respective statehouses.

Ramirez-Rosa says he was inspired to run for office after attending an NPA training session, beating a twelve-year incumbent Democrat. He also received backing from Reclaim Chicago, which grew out of the NPA’s new electoral push. Reclaim Chicago also backed Jesus “Chuy” Garcia’s unsuccessful bid to unseat Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel—the single name that elicited the most jeers at Populism2015. Progressives forced Emanuel into an unexpected run-off against Garcia, which they hailed as a major victory against “corporate influence in government,” even as he ultimately lost to Rahm by a large margin and expanded the progressive caucus in City Hall.

A number of NPA’s affiliates and allies have started to build the necessary infrastructure to become directly involved in electoral politics, launching 501(c)4s, Political Action Committees, and other independent political organizations. Traditional, tax-exempt 501(c)3s can’t be involved in political campaigns and have restrictions on their lobbying activities. By contrast, 501(c)4s can devote unlimited time lobbying policymakers on specific legislation and delve directly into campaigns, and the number of groups seeking 501(c)4 status has swelled since 2010. (The IRS became embroiled in controversy when it was revealed that 501(c)4 with Tea Party-linked names were receiving extra scrutiny.)

“We have been going after candidates big time,” says Cherie Mortice of the Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement (CCI) Action Fund, which launched a few years ago to expand Iowa’s CCI’s political lobbying. Similar activist groups have launched similar political arms recently in New York, Minnesota, Kentucky, Minnesota, Kansas, New York, California, and elsewhere.

“We want to go out and we want to be able to directly endorse a candidate. We want to sit down face to face. We want to show them our agenda and say you’re either with us or against us. And they know if they’re against us, we’re probably going to show up in a way that they’re not going to be happy with,” said Mortice, a retired schoolteacher from Des Moines. (Iowa CCI activists heckled Mitt Romney in 2012, prompting him to respond with the infamous line, “Corporations are people, my friend.”)

“There has been a maturation, as well as awareness that has changed over the last four years doing this work,” says Sayu Bhojwani of the New American Leaders Project, which prepares first- and second-generation immigrants to run for office. “We’ve turned out votes for our allies, and our allies haven’t always allied with us. We need to groom our own leaders.”

Many progressive activists remain skeptical about whether they should try to make inroads within electoral politics at all in a post-Citizens United world of billionaire donors. Unlike their Tea Party counterparts, activists from Occupy Wall Street largely wrote off electoral politics as a means for effecting change, rejecting partisan politics as hopelessly corrupt. There were “strong disagreements as to whether Occupy should support voting at all, bespeaking an even more ardent resistance to entering politics in a manner where an Occupy voice is expressed in any sort of partisan way,” activist Harry Waisbren wrote in Daily Kos shortly before the 2012 elections.

By contrast, the Tea Party’s rapid ascendancy into electoral politics has been devastating to progressives and Democratic Party stalwarts alike: The movement helped push the national party to the right through scores of successful primary challenges; fueled a wave election that allowed Republicans to lock in their gains through gerrymandering after the 2010 census; and helped turn out enough voters in 2014 to give Republicans control of 69 of 99 state legislatures, as well as the largest House majority since 1929.

Democrats held onto the presidency in 2012 and have a good chance of doing so again in 2016. But the GOP’s down-ballot victories have wiped out who knows how many of tomorrow’s progressive leaders before they can start rising. “We have to be like the right—we have to look to the future,” said Snyder, the Michigan United activist.

Gloria Totten’s message to progressive activists is even simpler. “Get over it,” says Totten of Progressive Majority, which focuses on recruiting and preparing candidates for down ballot races. “Get over your disdain of politics. Get over the fact you think it’s a dirty process. Get over the fact that you think raising money is bad. If you don’t get over it and participate, we’re the ones who’re going to suffer,” she said.

Post-Occupy, activists have moved closer to the voting booth as a more direct means to achieve their ends. The “Fight for $15” minimum wage strikes have pushed not only corporations, but also city and state governments to mandate higher wages. Those gains were not only in urban progressive enclaves, but also in four red states that hiked their minimum wage in November through successful ballot initiatives. In early April, voters in Ferguson, Missouri, turned out in record numbers and elected two black candidates to the city council.

Activists haven’t forsaken the 2016 presidential race, promising to keep Clinton on watch when the time comes. “I don’t think that’s where we’re focused right now. But will we get out there and push like hell? Yeah—we will hold her accountable,” said Mortice. Like many progressives, she is particularly wary about Clinton’s position on the Trans-Pacific Partnership—the trade pact that Clinton praised as secretary of state but has since hedged on.

Focusing on local and state elections, however, could make it easier for activists to overcome the pervasive cynicism surrounding Washington politics while retaining some measure of populist authenticity. “These representatives aren’t necessarily smarter than us in any way,” said Noor Ahmad of Michigan United, who mobilized activists after the fatal shooting of a black woman by Ann Arbor police in February. “We are the ones that need to run for office and represent our community. Who should be in power? We should be in power!” she concluded at Populism2015, as the crowd roared in agreement.

Ben Chin, a progressive activist with Maine’s People Alliance, recalled Representative John Lewis’s transition from civil rights activism to elected office. “There’s only so far we go on our issues when it’s always somebody else—when it’s not one of us that’s on the other side of the table when we’re negotiating,” Chin, who’s running against the GOP mayor of Lewiston, Maine, said at the conference.

Activists risk losing something as well: One reason the Tea Party movement had so much electoral clout was because it converged with the mainstream—and corporate-backed—groups like Freedomworks and Americans for Prosperity, essentially becoming an extension of the Republican Party. Meanwhile, some of the most prominent grassroots Tea Party groups have been hobbled by infighting and fiscal woes as the fundraising cash has poured in.

In a 1965 essay, civil right activist Baynard Rustin outlined some of the pitfalls in moving from protest to electoral politics, but ultimately made the case for taking hold of institutional political power to achieve the movement’s ends. “There is a strong moralistic strain in the civil rights movement which would remind us that power corrupts, forgetting that that absence of power also corrupts,” he wrote.

This article has been updated.