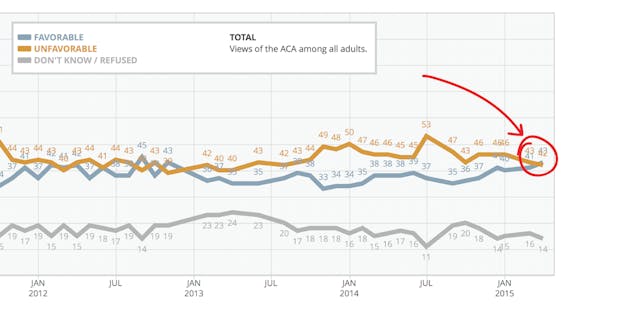

Two days ago, I observed that the Affordable Care Act remained barely unpopular, with a 2 percent unfavorability margin that could be attributed entirely to elderly people who have little-to-no stake in the law.

A day later, the Kaiser Family Foundation updated its tracking poll numbers and revealed that the margin hasn't merely disappeared: It has reversed.

Even accounting for cranky old people, Obamacare's popularity is above water, 43 percent to 42 percent, and its trend lines are improving. The numbers reflect a steady but remarkable climb back from November 2013, when the Healthcare.gov outage left the law under water by a 16-point margin. Part of the reversal owes to the simple fact that the website now works. But even that only returned the numbers to their pre-launch levels, when the law was under water by margins of 4 to 8 points.

It’s hard to know what accounts for the rest. I’d wager the 20 million Americans who now count on Obamacare for their insurance coverage have something to do with it.

Whatever explains it, conservatives are adjusting to the new reality with predictable equanimity.

1) @KaiserFamFound poll doesn't measure public opinion of #ACA because the ACA isn't what the public is experiencing. http://t.co/fuQtg53bf0

— Michael F. Cannon (@mfcannon) April 21, 2015The law’s changing fortunes confound conservatives in part because the public’s views have polarized along a partisan axis. Obamacare derives nearly all its support from Democrats and liberals; its opposition is almost entirely driven by Republican and conservatives. Conservatives who spend their days surrounded by conservatives find it hard to fathom that more people like than dislike the law—or, more accurately, that the hardened opposition to the law is a minority view.

All of this will bedevil Republicans in their presidential primary and in the general election.

The people who will select the Republican presidential nominee are among the most committed conservatives in the country. By and large they will not tolerate ambivalent candidates who don’t like Obamacare but understand that fanatical opposition to the law is a general election liability.

Back in 2012, when Obamacare was largely an abstraction, this was an easier line to walk. Twenty million beneficiaries complicate that. Some of those 20 million are Republican primary voters. The trouble will begin when an elusive conservative Obamacare supporter pokes his head up to challenge the candidate field: How will your position on Obamacare not ruin me?

In such an event, candidates eyeing the general electorate will want to promise to leave the voter’s coverage intact. If they succumb to that temptation, they’ll be stampeded by dark horses. If they resist, and put conservative dogma ahead of peoples' livelihoods, their heartlessness will hound the primary winner in the general election, as Mitt Romney’s plan to encourage unauthorized immigrants to deport themselves hampered him in his 2012 race against President Obama.

Hillary Clinton will know how to exploit this. Her campaign is betting on the proposition that the Democrats’ coalition is just as stable as, but slightly larger than, the Republicans’. Obamacare polling supports this theory. It’d be a mistake to think of Obamacare as a popular law, but the share of the population that likes or is at peace with it clearly exceeds the share ready to repeal it. The voters who re-elected Obama will return to put Clinton in office, if they’re convinced that a Republican president will erase Obama's accomplishments. A Republican candidate who navigates his primary field by promising to repeal Obamacare will do just the trick.