Republicans have known for a long time now that the right’s absolutist position on the Affordable Care Act—that it should be repealed outright—is a political loser. Anti-Obamacare purism has never polled well, and now that the law is deeply entrenched, the practical implications of full repeal have made it a dead letter among all but the most reactionary conservatives in the Republican Party. For years, GOP leaders and Republican presidential aspirants have coalesced around the view that the law should be repealed and replaced, perhaps with a plan that will replicate all of Obamacare’s popular goals.

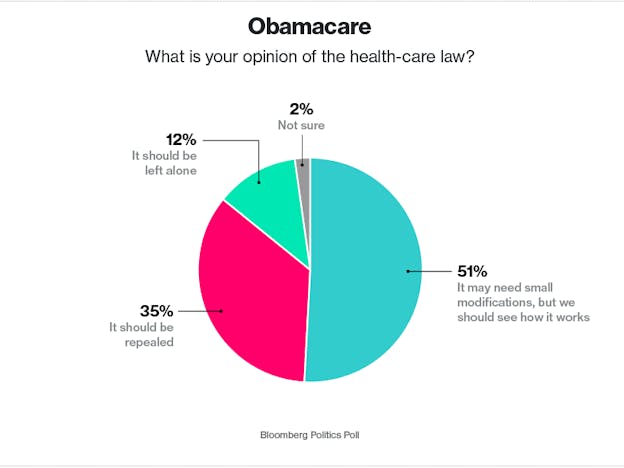

A new Bloomberg poll should convince Republicans that this, too, will not fly with the public.

Bloomberg found that only 35 percent of American adults supports outright repeal. The surprising part, though, is the composition of those who don’t support outright repeal. A small minority is fully satisfied with the law, but a bare majority, 51 percent, believes the ACA “may need small modifications, but we should see how it works.”

The segments of the populations who support repeal, and “repeal and replace” are nearly coterminous. Which means that tacking “replace” on to “repeal” doesn’t widen the appeal of the conservative position at all.

But even the 35 percent support figure for repeal overstates the scope of the law’s unpopularity. Or, more accurately, we should ignore a sizable chunk of Americans who want to repeal Obamacare. Repeal is a fringe position, in that Americans oppose it overwhelmingly. But it’s also fringe in that those who do support it reside disproportionately on the periphery of the law itself. Their opinions matter insofar as they’re eligible to vote, but for heuristic purposes we should ignore them.

Dell Stone, quoted in the Bloomberg article, is a textbook case.

Stone, 83, says she “certainly hopes” the law gets repealed. She blames limits on medical testing in the act for her need to take cholesterol medication for three months this year after her cardiologist wasn't willing to repeat a seemingly inaccurate but very high reading. “The doctors are very dissatisfied, and many of them are not able to give their patients the attention that they feel that they need because they can’t have too many appointments, too many tests,” said Stone, a retired elementary school principal from Alexander City, Alabama.

Stone’s antipathy to Obamacare stems from somewhere, but not from her interaction with the law itself. At 83, her frustrations with out-of-pocket health care costs are at best only tangentially related to Obamacare. She isn’t shopping for insurance on the federally facilitated Alabama exchange. She’s on Medicare. And she probably isn’t unhappy that the law increased her taxes because it almost certainly didn’t.

Only a third of the country supports full repeal, and, like the Republican coalition itself, it is a very old third—comprised of the only people in the country with almost no stake in the law’s core costs and benefits.

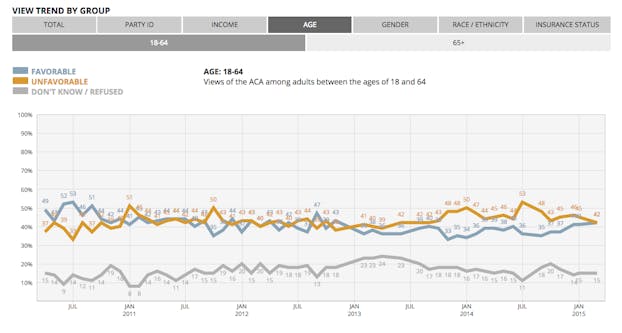

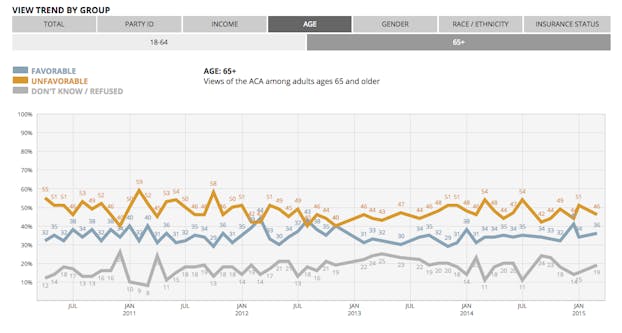

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, whose tracking poll is a touchstone for measuring public sentiment about Obamacare, the law is under water—barely. Forty one percent of respondents hold favorable views of the ACA, while 43 percent hold unfavorable views. But if you break it out by age cohort, you find that that two percent margin is entirely attributable to people who have aged out of the program.

Among 18- to 64-year-olds—the people who pay for the law, or are eligible for the law’s benefits, or might become eligible for the law’s benefits at some point in the future—Obamacare is breakeven. Forty two percent favorable, versus 42 percent unfavorable. Among those whose opinions we should generally ignore on this issue—old people—it’s a bloodbath. Only 36 percent view the law favorably, while 46 percent view it unfavorably.

It’s not that the elderly would experience no change at all if Obamacare were to be repealed. Their prescription drug costs would increase, their Medicare advantage premiums and benefits might change. But even if seniors have legitimate gripes with the ACA’s Medicare reforms, it doesn’t stand to reason that we should care—at all—about their views of the law’s coverage expansion in general.

This isn’t a revealed bias, as when Washington Examiner’s Byron York wrote that Obama’s “sky-high ratings among African-Americans make some of his positions appear a bit more popular overall than they actually are.” It’s an argument that we shouldn’t give everyone’s views about Obamacare equal weight. The public sentiment animating the repeal movement is derived from people who have a negligible stake in the law, but who would like to throw millions of people off their new insurance plans before they die. Presumably we’d have no problem ignoring old people if they objected to child tax credits financed by working-age people. We should ignore them in this instance, too.