Whether it is Jimmy Carter watching more than four hundred movies in the White House cinema or Barack Obama telling people that the flamboyant killer Omar on HBO’s “The Wire” is his favorite character, presidents have long engaged with pop culture. The content of that pop culture, however, has changed dramatically over the years. Here, in the fourth of a series of short installments from What Jefferson Read, Ike Watched, and Obama Tweeted: 200 Years of Popular Culture in the White House, we look at some of the presidents favorite ways to pass the time. Read the first, second, and third installments.

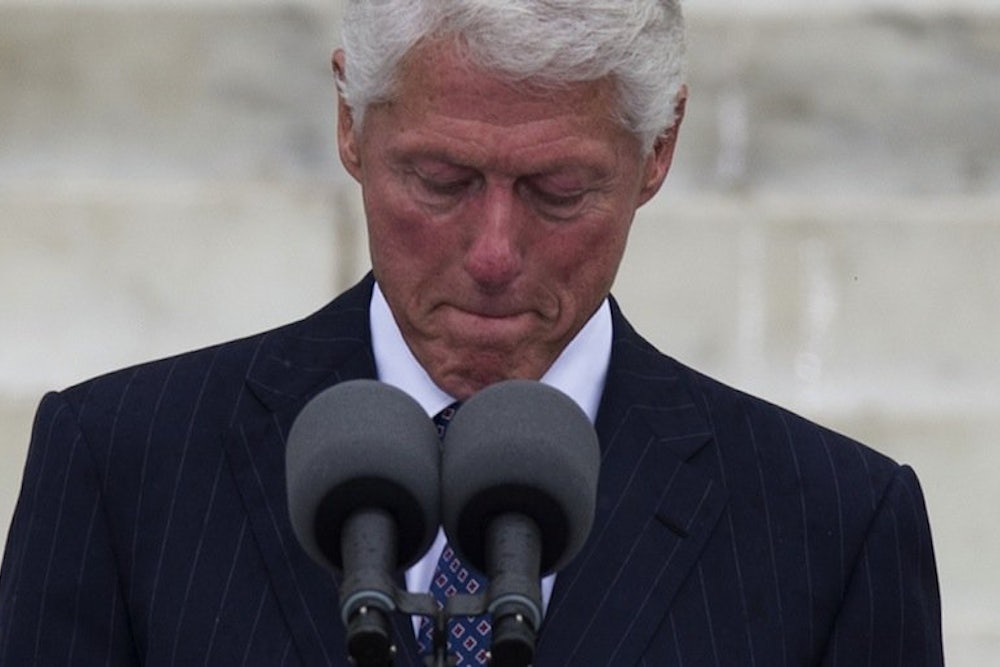

In 1992, Bill Clinton successfully adopted Fleetwood Mac’s ’70s hit “Don’t Stop Thinking about Tomorrow,” to relate to baby boomers raised on this and other top-forty hits. The campaign played the song so often that The New York Times’ Caryn James referred to it as Clinton’s “endlessly replayed 1992 campaign theme.” The song conveyed youthful optimism, emphasizing the contrast between Clinton and his generation-older opponent, George H. W. Bush. As the Los Angeles Times’ Jeff Boucher wrote, the song “musically encoded both Clinton’s baby-boomer target audience and his message.” Music had become another language politicians needed to master.

Clinton was, as a 1997 documentary described him, a “Rock and Roll president.” In his 1992 campaign for president, he famously donned sunglasses to play the saxophone on the Arsenio Hall Show, “one of the defining moments of that Presidential campaign.”

By the 1990s, rock and roll had become mainstream. The music that had seemed subversive in the 1960s was now safe fare for a political convention. New forms now appeared to replace rock as the subversive music of the moment.

Rap came along to fill that void. The appeal of rap, David Samuels wrote in his groundbreaking cover story on rap in The New Republic, was that it allowed white suburban teenagers to absorb the ghetto experience without facing any of its physical dangers.

It was this appeal, however, that concerned parents, cultural critics, and, increasingly, politicians as the 1992 presidential election approached. The specific offender in the 1992 campaign was Ice-T and his “gangsta rap” song “Cop Killer.” The lyrics—“Cop killer, better you than me / Cop killer, f**k police brutality! / Cop killer, I know your mama’s grievin’ (f**k her) / Cop killer, but tonight we get even”—seemed to condone or even encourage anti-police violence.

Republicans thought that with “Cop Killer” they could at last turn the Democrats’ cozy relations with the music industry against them. Clinton appeared to be in a quandary. If he condemned Ice-T, he risked alienating his deep-pocketed supporters in the entertainment business and the indispensable black vote. At the same time, there was widespread outrage over the song.

Clinton benefited from some plain, old-fashioned luck in the form of a failed rap singer and activist called Sister Souljah. When the policemen whose beating of Rodney King had been captured on video tape were acquitted, rioting broke out in Los Angeles. Sister Souljah told the Washington Post’s David Mills, “I mean, if black people kill black people every day, why not have a week and kill white people?” This was Clinton’s opportunity. In a campaign appearance with Jesse Jackson, he criticized Sister Souljah. “Her comments before and after Los Angeles were filled with a kind of hatred that you do not honor,” he told Jackson’s supporters. The remark upset Jackson (and Sister Souljah), but it appeared that Clinton was not beholden to his party’s special-interest groups and that he shared the concerns of the white working class—Nixon’s “silent majority.” The columnist Clarence Page cited the debt Clinton owed to Souljah and declared the episode “[t]he most important moment in the 1992 presidential race …”

Later that summer, George H.W. Bush—whose personal tastes ran to Broadway tunes and country music—denounced music that glorified violence against the police as “sick,” and everyone knew that he was referring to “Cop Killer.” The effort was ineffective. Clinton had already defused the issue with his criticism of Sister Souljah, and he emerged unscathed. Still, rap remained subversive, even dangerous, for politicians. Rappers would have to wait until Barack Obama’s presidency until they were invited to the White House.

Excerpted from What Jefferson Read, Ike Watched, and Obama Tweeted: 200 Years of Popular Culture in the White House. Tevi Troy is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute.