Whether it is Jimmy Carter watching more than 400 movies in the White House cinema or Barack Obama telling people that the flamboyant killer Omar on HBO’s “The Wire” is his favorite character, presidents have long engaged with pop culture. The content of that pop culture, however, has changed dramatically over the years—as has what it reveals. Here, in a the second of a series of short installments from What Jefferson Read, Ike Watched, and Obama Tweeted: 200 Years of Popular Culture in the White House, we look at some of the presidents’ favorite ways to pass the time. Read the first installment here.

In the nineteenth century, American theater evolved from a vulgar medium that offended genteel sensibilities to one that highlighted increasingly popular and democratic forms of expression. The Founders envisioned enlightened leaders presiding over an educated and vigilant citizenry. Theater, they hoped, would encourage that citizenry in virtue. But democracy proved to be loud and unruly, and the theater that emerged in nineteenth-century America was very different from the vision of the Founders. It was bawdy, raucous, lively, and above all democratic.

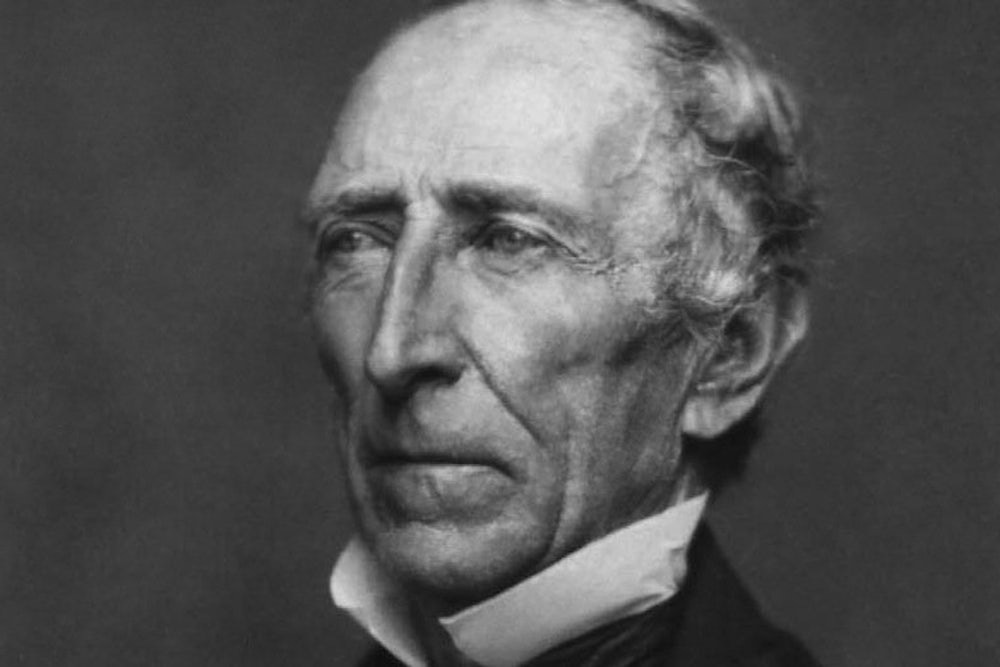

Virginia’s John Tyler loved Shakespeare from an early age and would often quote or allude to him in public and private communications. Tyler had an elite background. His father had been Thomas Jefferson’s roommate at William and Mary. Tyler attended his father’s alma mater, beginning at the precocious age of twelve and graduating at seventeen. When he ran for vice president on the “hard cider and log cabins” ticket with William Henry Harrison in 1840, he tried to downplay this upper-class education. But he was well versed in music, poetry, and literature and collected an impressive library of 1,200 books.

Still, Shakespeare was Tyler’s favorite, and he felt comfortable citing the bard, knowing that his audience would understand him. In 1855, after he had moved on from the presidency to the role of “well-read elder statesman,” he gave an important speech on slavery and secessionism to the Maryland Institute. The speech was filled with literary allusions. He struck a note of optimism by making an apparent reference to Edgar Allan Poe, who had been a household name since the publication of “The Raven” in 1845: “I listen to no raven-like croakings foretelling ‘disastrous twilight’ to this confederacy …” He also made an adamant stand against secession, doubting that “a people so favored by heaven” would “throw away a pearl richer than all the tribe.” (His views on this subject would change after the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, and he was a member of the Confederate Congress when he died in 1862.) His reference to Othello in the central point of his argument reflects his confidence that his listeners would share an appreciation for Shakespeare.

Tyler could quote Othello in a political speech because even his most simply educated countrymen were taught Shakespeare and because so many people went to the theater. Average Americans attended plays far more often than we might imagine. One nineteenth-century Massachusetts man managed to see 102 shows in 122 days. Not only must he have been a very determined theater-goer, but he must have had many opportunities. As Heather Nathans observes, “[t]hat he could find 102 opportunities in 122 days to be part of an audience underscores the importance of performance culture in America during this period.” The shows themselves were varied, including not just Shakespeare, but also singers, musicals, minstrels, and orators, both professionals and amateurs. Presidents, as well as regular citizens, both followed and attended.

Excerpted from What Jefferson Read, Ike Watched, and Obama Tweeted: 200 Years of Popular Culture in the White House. Tevi Troy is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute.