Trump Serves Up a Word Salad That The New York Times All But Ignores

The Washington Post led with his incoherent comments about childcare in a Thursday speech. In the Times’ account? Barely a word.

For months, Donald Trump’s frequent lapses into incoherence—the half-sentences that suddenly veer off toward a distant galaxy, the asides that limn the virtues of Hannibal Lecter—have been mostly fodder for late-night TV hosts. Morning Joe has covered them consistently, but for the most part, the mainstream press has ignored them, either cleaning up Trump’s actual words so they made more sense on the printed or pixelated page or just not printing them at all.

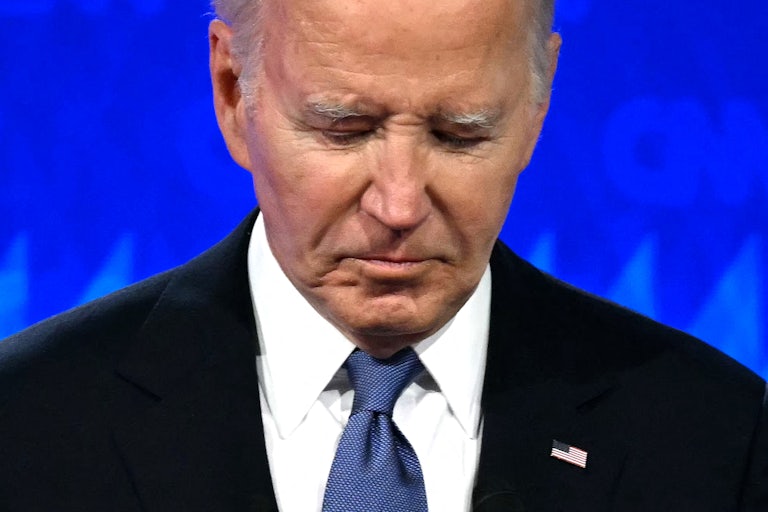

This was easier to do when Trump was running against Joe Biden, who sometimes also lost the rhetorical thread, and whose age was a constant news story (not without justification). But now that Trump is running against a younger and more energetic opponent who tends to speak in full, logical sentences and who doesn’t go on rants about bacon and wind power, his mental state is rightly becoming more of a story. As my colleague Greg Sargent put it yesterday: “Trump’s mental fitness for the presidency deserves sustained journalistic scrutiny as a stand-alone topic with its own intrinsic importance and newsworthiness.”

Which brings us to Trump’s appearance Thursday before the Economic Club of New York. I watched some of it. In fairness, reading from his prepared remarks, he was coherent. He rattled off a string of statistics about the economy under his presidency, many of which were actually true, or close enough; when he got around to describing the horrors “Marxist” Kamala Harris had visited upon America, his claims were a lot less true. (He said “crime is rampant, and fleeing is the number one occupation” in California, but crime is trending down in the state this year, and the recent population declines have been turned around too—not that Harris has control over these issues one way or another.)

Then came the question-and-answer period. A woman among the handful assembled on stage asked Trump if he would commit to passing childcare legislation, and if so what his specific proposal would be. Here’s the answer in part, as put out in a tweet by the Harris campaign:

“Well, I would do that, and we’re sitting down, you know; I was, somebody, we had Senator Marco Rubio and my daughter, Ivanka, who was so impactful on that issue.… But I think when you talk about the kind of numbers that I’m talking about that because the childcare is childcare, couldn’t, you know, there’s something you have to have it, in this country you have to have it.”

Trump’s answer was longer than that, but when he got around to something resembling a response, it was that his tariffs on China are going to pay for everything, no problem. Just like deporting people is going to solve the housing crisis.

A few quick facts. In the nineteenth century, before the individual income tax became a permanent fixture of life, tariffs accounted for most of the government’s revenue (at a time when the government did very little—stood up an army, ran a postal service, etc.). But today, according to the Council of Economic Advisers, import duties bring in only around 2 percent of the federal government’s total revenues. If you want to lower taxes on corporations and the rich, as Trump does, tariffs would need to be substantially jacked up to make up for the lost revenue (although of course in the Candyland in which Republicans and their economists live, reducing tax rates does not reduce revenue, which is probably the single biggest and most insidious policy lie of the last 50 years). And of course, as the CEA and many others argue, much higher import levies are “likely to spark retaliatory tariffs that reduce U.S. exports and subsequently induce transfers of collected duties to impacted U.S. businesses.”

Now let’s get to the point here: the media. Specifically, The New York Times.

I looked Friday morning at the way the Times and The Washington Post covered the speech. The Post’s article, to my astonishment, was mostly about the childcare word salad. “Trump offers confusing plan to pay for U.S. child care with foreign tariffs,” ran the Post’s headline.

The Times’s story was by no means favorable. Under the headline “Trump Praises Tariffs, and William McKinley, to Power Brokers,” the article adopted a gently skeptical tone toward Trump’s promise that tariffs would solve everything. It even mentioned the words “child care,” once.

But the article didn’t bother to quote him on the topic. Why? It could be that the reporter didn’t think it was newsworthy (or perhaps it was an editor, since the Times’ election news blog did partially quote Trump). But this is exactly the point Sargent and others are trying to make: that Trump’s frequent incoherence is in and of itself news. It should be reported on. He should be quoted verbatim, not in a partial way that sanitizes his words and cleans them up.

Why? Because his mental fitness at age 78 to be president for the next four years is a legitimate issue. I’ve covered, and simply watched as an interested citizen, a lot of presidential candidates. Dozens, maybe hundreds, if you count Democrats and Republicans who ran in primaries. I’ve watched hours of debates and attended events like the once-famous Iowa Straw Poll in 1999, at which 11 Republican candidates spoke. I’ve never heard a candidate who talks in such a dissociative, rambling, confused way; never heard a candidate so obviously bluffing his way through certain policy questions.

The conventions of objective journalism are such that reporters tend to use “good” quotes. Reporters favor politicians’ pithiest and most succinct quotes, because reporters themselves are trying to be pithy and succinct, and ergo logorrheic and nonsensical just doesn’t fit the plan. I’ve been there, I’ve done that. Guilty.

But here’s what’s different. Until Trump, using the pithiest and most succinct quote never amounted to a quasi-conspiracy against reality. Now it does. Maybe the voters will decide that Trump’s incoherence doesn’t matter. But they at least need to be presented with the evidence to decide for themselves.