Kyrsten Sinema Is Proud That She Has No Beliefs

In a rare interview, the Arizona senator gets tangled up in a web of her own ideological contradictions.

“No.” This is what Arizona Senator Kyrsten Sinema said when asked if there’s an ideological through line in the votes she has taken in the Senate.

Sinema takes pride in her transformation from young idealist to defender of the status quo as an example of maturity. Alas, what the Arizona senator views as some unique, independent approach to politics is simply what hegemonic forces in America have encouraged for decades: You can dream of a better world when you’re young, but you better wise up when you get old enough to become a cog in the machine that prevents such a fantasy from happening in the first place. (Note: This tradition of relinquishing idealism is now being upended by millennials and Gen-Z.)

Sinema seldom engages with the press; in fact, she famously seldom gives more than a minute’s attention to anyone unless they have lots of money, lots of power, or both. Consequently, hedge funders and private equity titans all seem to have her on speed dial whereas her own constituents have to stalk her in public to earn a moment of her time. But the Arizona senator bucks this trend in a recent interview with The Atlantic, in efforts to show that her approach to politics “works.” Sinema comes across as both staunch in ignoring the advice of others and too willing to skate around her own self-purported principles.

Sinema has faced criticism for appearing to have abandoned previous ideals, serving now instead as a foot soldier for plutocratic elites. But she’s pointedly proud of her ideological shift, and refers to her youthful political activities—protesting against the Iraq War, marching in sweltering heat in support of undocumented immigrants, spearheading a historic and successful effort to defeat an Arizona gay marriage ban—as “a spectacular failure.” Abandoning those youthful ideals, she says, is a sign of “age and maturity,” in which “new information” led the “lifelong learner” to adopt a different approach to politics.

“You can make a poster and stand out on the street, but at the end of the day all you have is a sunburn,” Sinema told The Atlantic. “You didn’t move the needle. You didn’t make a difference … I set about real quick saying, ‘This doesn’t work.’”

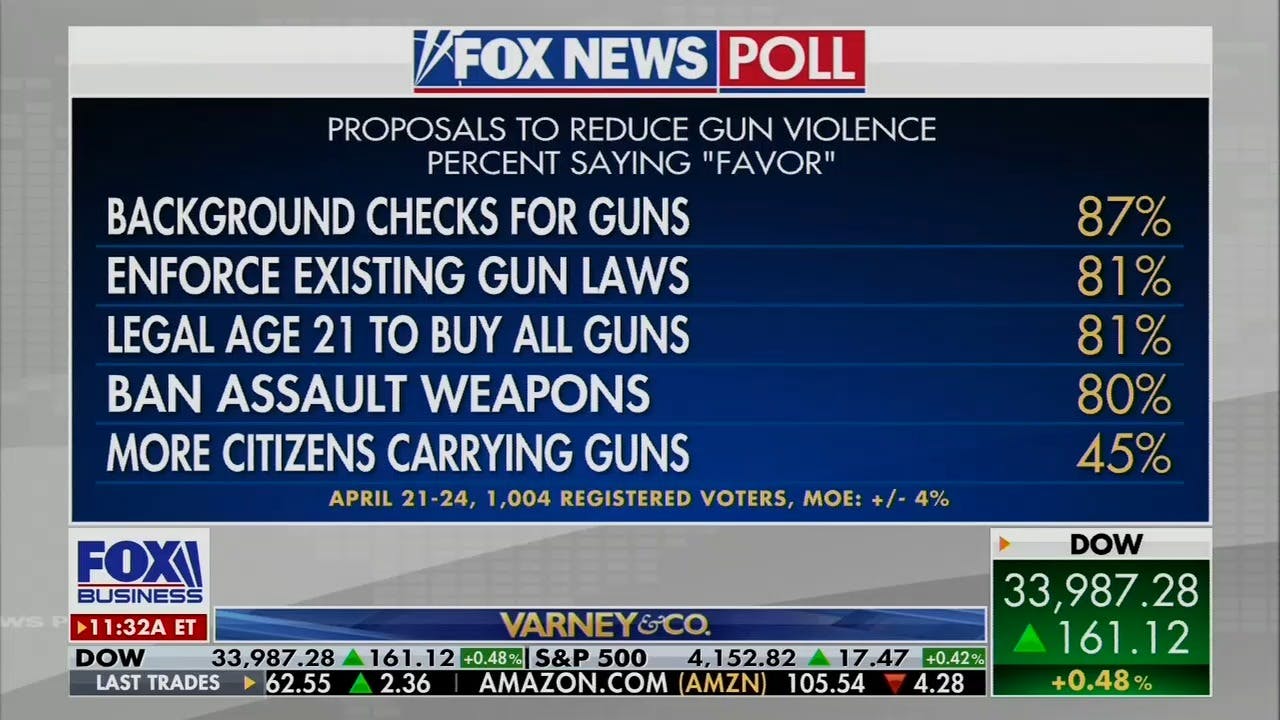

Sinema’s supposed concern with moving “the needle” connects to her view of herself as “practical,” as someone who moves efficiently to solve problems and broker deals, like the 2021 infrastructure package and 2022 gun safety bill following the Uvalde, Texas, school shooting. Naturally, there are some factors that complicate her self-evaluation.

For one, both bills were severely watered down (in no small part from Sinema’s own hand) and fall short of what is necessary to genuinely solve the problems they sought to address. The guiding principle to compromise in order to achieve something doesn’t carry as much weight when the compromise imperils the original legislative goals from being achieved. It certainly seems significantly at odds with Sinema’s self-aggrandizing claim that she is “a long-term thinker in a short-term town”—there’s hardly anything more short-term-minded than continually lobbying for half-measures that ensure the underlying problem will fester, continually demanding the attention of lawmakers and adversely affecting ordinary Americans.

Moreover, the “problems” Sinema is trying to solve do not just exist in the ether. Her own approach to politics in a narrowly divided Senate is one source of the problems stopping the government from enacting meaningful change. The Arizona senator has been staunch in her opposition to eliminating the filibuster, for instance, which requires 60 votes for most bills to pass in the Senate. Eliminating this barrier would allow a simple majority of the Senate to enact legislation. Sinema famously has an illogical and ahistorical position on the filibuster that doesn’t track with the Founders’ ideals.

Sinema’s insistence on maintaining this status quo is grounded in her belief that it prevents parties from imposing their agenda with narrow majorities—as if conservatives have not benefited from structural advantages like the Electoral College that have allowed the right wing to impose its agenda with not just narrow but often unearned or illusory majorities, or through the courts (banning abortion and attacking labor and calling corporations “citizens” are not popular policies in the slightest, but all have been imposed by conservatives all the same).

“When people are in power, they think they’ll never lose power,” Sinema said two years after a Republican-fomented attempt to overthrow the results of an election in which the party she fled from won a mandate to pass policies she has played a central role in preventing from happening.

Much ink has been spilled questioning Sinema’s motives. Is she just a capital-serving villain? Is she playing some long game? Is she just now a moderate who believes in the system that she rightfully saw as broken a few decades ago? Or does she actually have no ideology?

For the sake of argument, what if we imagine she truly believes in her approach? There often can be nefariousness drawn from the actions of the most powerful in our society—either intentional, or at least in their outcome. And can we recall that the most powerful are human beings too: shrouded by their personal experiences and biased by what they believe or come to believe is correct (think of how Elon Musk’s attitudes have only become more and more reactionary as he structurally surrounds himself more and more with sympathetic employees and blue check reply guys).

What some may see as subservience to power interests and shady, consistent avoidance of engaging with the public may be imagined by others as unorthodox tactfulness. But the impacts are the same nonetheless: The possibilities of politics are being hijacked by a lawmaker whose imagination has been lost. If Sinema truly is a “lifelong learner,” may we ask her, genuinely, to consider how she may now be stricken from the very maladies of establishment thinking to which she presumes herself to be immune.