Finally, a Gas Stove Proposal That Cares About Poor People

The District of Columbia City Council is considering a bill that will allow low- and moderate-income households to switch out their gas stoves—if they so choose—for free.

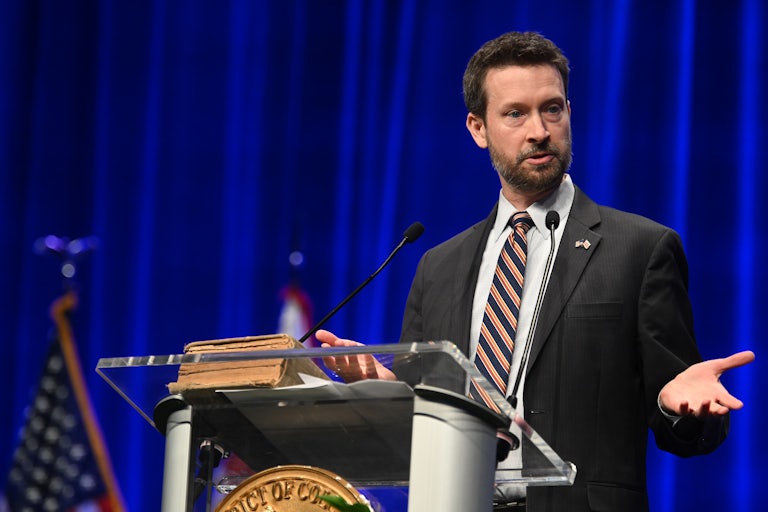

Last Friday, District of Columbia Councilmember Charles Allen led five colleagues in introducing a bill to address the health dangers of gas stoves in the home. You might think, given all the coverage of the gas stove wars in the past month, that this legislation was just the latest salvo in the growing contest between Democratic policymakers who want to regulate gas stoves and Republican policymakers who want to outlaw any law that outlaws gas stoves.

The D.C. bill differs significantly, however, from how the cities of Berkeley, San Francisco, and New York—as well as Montgomery County, Maryland—have approached gas stove policy. Whereas those places have banned gas hookups in new buildings, Allen’s bill aims to make stove-switching affordable in existing moderate- and low-income homes. The idea, per a release on Allen’s website, is to use federal funds made available by the Inflation Reduction Act to help households earning less than $80,000 switch out their old gas stoves for free, allowing them to buy and install an electric or induction stove with “no out-of-pocket costs.” It also proposes incentives for others to switch: a fee for installing “new fossil fuel-burning appliances during major renovations,” for example, and a prohibition on installing these devices in public housing. But the legislation’s main goal is enabling low-income households to choose what kind of device they want in their home—and, if desired, get rid of polluting stoves that may have been installed before people were widely aware of the health risks.

Allen’s bill, which was originally submitted late last year before the gas stove issue exploded into public consciousness, is an important policy innovation. And it points toward a way to avoid the whole bogus culture war that ignited last month when the U.S. Consumer Product Safety commissioner gave a quote to Bloomberg that suggested his agency was open to banning gas stoves to protect consumers.

While the American right immediately jumped on this quote as a consumer rights issue—the government is coming to steal your stove!—the people who really get screwed by gas stoves, as TNR columnist Liza Featherstone recently pointed out, are those who don’t have much choice about their appliances to begin with. In other words: renters, low-income households, etc. The bottom line is that regardless of your opinion of gas stoves as a cooking device, no one should be stuck living with an appliance that is poisoning them.

The Berkeley, San Francisco, and New York City bans on new gas hookups didn’t focus on this, and that may be because the rationale offered at the time for those bans was climate change: specifically, gas stoves’ copious emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. The bans on new gas hookups were presented as a way to help each city meet its emissions targets going forward.

But as researchers have been stressing for decades, methane emissions aren’t the only problem with gas stoves. Since the late 1970s, studies have been showing a link between gas stoves and respiratory illnesses, particularly in children. And research in the past year has highlighted that the stoves are also leaking benzene, a known carcinogen with no safe exposure limit. In other words, gas stoves aren’t just a collective risk when it comes to the climate—there’s ample evidence that they’re poisoning people in their homes.

Bans on new gas hookups are probably a good idea from a climate perspective. But they don’t help people currently stuck with gas stoves in their homes. What the D.C. bill gets right is that giving people the means to remove a toxic appliance from their homes ought to be a clear ethical priority for policy going forward. In addition, reframing the debate over gas stoves as a matter of tenants’ rights—of giving people the ability to choose not to be poisoned—may be a smart political strategy to avoid the nonsensical culture wars that have become a sad feature of modern American life.

![]()

Good News

The Inflation Reduction Act is, as intended, stimulating green job creation. More than 100,000 clean energy jobs have been announced since last August, according to a new report.

![]()

Bad News

Thirty-four percent of plants and 40 percent of animals in the United States are at risk of extinction, and 41 percent of U.S. ecosystems are at risk of collapsing, according to a report released Monday by conservation research group NatureServe. The biggest threats to terrestrial species are from invasive species or disease and agriculture, with climate change close behind, while freshwater animals are particularly threatened by pollution and human water management practices. (Read Prem Thakker’s piece about how biodiversity fell off the Biden administration’s agenda in the past year.)

Stat of the Week

.png)

That’s how much energy could be generated simply by putting solar panels on the roofs and parking lots of every Walmart in the U.S., engineering professor Joshua Pearce told The Washington Post. (That’s as much as, or more than, the amount expected to be generated by a new and unprecedentedly ambitious parking-lot plan in France.)

Snidely Whiplash Award:

The National Oilheat Research Alliance and the Propane Education and Research Council have been funding and disseminating misinformation to dissuade homeowners from switching to heat pumps, the Post reports. Heat pumps can dramatically reduce a household’s energy bill and are eligible for federal tax credits due to provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. The propane trade association “has put out training material coaching installers how to dissuade customers from switching to electrical appliances.” The heating oil trade association, meanwhile, has been paying for campaigns telling Maine residents—many of whom are looking to switch from ultra-expensive oil-based heat—that heat pumps won’t work in their climate.

Elsewhere in the Ecosystem

Cars are rewiring our brains to ignore all the bad stuff about driving

A new study by a team in Wales suggests people suspend a lot of their values when it comes to defending car culture. The way they tried to measure this is fascinating, comparing subjects’ opinions on a given car situation with another analogous ethical situation not involving cars to identify unconscious biases:

For example, people were asked to agree or disagree with the following statement: “People shouldn’t smoke in highly populated areas where other people have to breathe in the cigarette fumes.” Then they were asked to respond to a parallel statement about driving: “People shouldn’t drive in highly populated areas where other people have to breathe in the car fumes.”

While three-fourths of respondents agreed with the first statement (“People shouldn’t smoke...”), only 17 percent agreed with the second (“People shouldn’t drive...”).

Another statement addressed values around theft of personal property. Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement, “If somebody leaves their belongings in the street and they get stolen, it’s their own fault for leaving them there and the police shouldn’t be expected to act,” as well as the parallel statement, “If somebody leaves their car in the street and it gets stolen, it’s their own fault for leaving it there and the police shouldn’t be expected to act.”

Only 8 percent of people disagreed with the first statement, while 55 percent of people disagreed with the second one.

Read Andrew J. Hawkins’s piece on this at The Verge.

This article first appeared in Apocalypse Soon, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by deputy editor Heather Souvaine Horn. Sign up here.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)