The Mixed Messages of the Contraception War

Democrats and Republicans have put forth dueling bills that would, to varying degrees, protect the right to contraception. Both are dead on arrival.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the party with a majority in Congress must spend the months leading up to Election Day on bills that make the other party uncomfortable. That’s why House Republicans voted this week to sanction the International Criminal Court over its decision to pursue arrest warrants against Israeli leaders for the war in Gaza. It’s also why, on the other side of the Capitol building, Senate Democrats put forth a bill enshrining the right to obtain and use contraception.

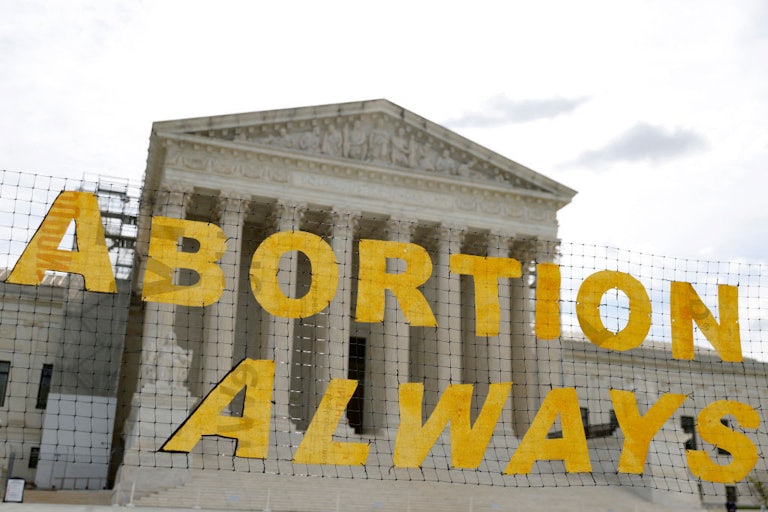

With the erosion of abortion rights in more than a dozen states since the Dobbs decision, and the threat that a future Trump administration could limit access to contraception, Democrats are hoping to capitalize on the overarching issue of reproductive care.

“We’re going to have Contraception Day here in the United States Senate, and everyone’s going to be put on the record, and if [Republicans] say it’s not under threat, then they should all just vote ‘yes’ in order to reaffirm that right,” said Democratic Senator Ed Markey on Wednesday.

The vote on the Right to Contraception Act on Wednesday was deliberately timed just weeks before the second anniversary of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, the first in a volley of bills intended to put Republican members in the tough spot of opposing measures on issues like birth control and in vitro fertilization.

’Tis a cynical political ploy on the part of Democrats, Republicans say, pointing to legislation by GOP Senator Joni Ernst that would protect access to birth control while enshrining the right of providers with religious objections to refuse to offer contraceptive care. (Democrats say there is nothing in their bill that would threaten religious freedoms.)

“They are more interested in playing politics than they are actually about securing the very things they’re talking about,” GOP Senator Katie Britt told reporters this week. “They’ve engaged in a summer of scare tactics, and they don’t care about the false fear they’re creating in women and families.”

Birth control was legalized nationwide nearly 60 years ago with the Supreme Court decision Griswold v. Connecticut. But reproductive rights advocates have long warned that contraception could be the next issue targeted by abortion opponents.

“Oh really? There’s no threat? That’s what they also said about abortion: that there was no threat to abortion,” Senator Elizabeth Warren told reporters on Wednesday. “Too many people fell for that last time. Nobody’s falling for it again.”

In his concurring opinion in the Dobbs decision, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas suggested that other precedents could be revisited, including the decisions legalizing same-sex marriage and contraception.

More recently, former President Donald Trump said he was “looking at” restrictions on contraception, although he quickly backtracked, insisting in a social media post that he would “never, and will never advocate imposing restrictions on birth control or other contraceptives.”

Nonetheless, Trump’s administration enacted multiple policies making it more difficult to obtain birth control, including placing restrictions on the federal Title X program, which provides a host of free contraceptive and reproductive services to low-income Americans. Although President Joe Biden repealed these rules, a second Trump presidency could reimpose them. Meanwhile, a playbook by the conservative Heritage Foundation for a potential second Trump presidency would label Ella, an emergency contraceptive, as a “potential abortifacient,” to be removed from the Affordable Care Act’s coverage of birth control.

Meanwhile, in several red states, some Republican lawmakers have called birth control methods “abortifacients,” incorrectly equating emergency contraception with abortion drugs. “Attacks against birth control aren’t theoretical bugaboos. It’s already happening at the state level,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said on Wednesday.

With the exception of Senators Lisa Murkowski and Susan Collins, Republicans remained largely unified in their opposition on Wednesday, despite the belief by some GOP senators that they should call Democrats’ bluff, as Punchbowl News reported. But for the Republicans who did vote in favor, the decision was obvious.

“If it’s a messaging bill, my message is I support a woman’s access to contraception. Pretty simple,” Senator Lisa Murkowski told reporters. “So if we’re gonna play messaging, that’s my message.”

Vibe Check

Each week, I provide an update on the vibes surrounding a particular policy or political development. This week: Why a transgender journalist is leaving congressional reporting, in her own words.

Jael Holzman, a climate journalist who most recently reported for Axios, announced this week that she is leaving congressional reporting. In an essay on Medium published earlier this week, Holzman, who is a trans woman, explained her frustrations with media coverage of trans rights and issues. I caught up with Holzman this week to discuss her decision to leave, and what reporters—particularly those who cover Capitol Hill—can do better. This interview has been edited and lightly condensed for clarity.

In this essay, you give an example of an issue that was under-covered by reporters on the Hill, which was the inclusion of language to ban government-backed health care insurance from covering sex- and gender-affirming care in the House GOP funding bills. I’d be interested to know more about why you think that was overlooked by reporters. Do you think that they didn’t know about it or that it just was deemed less of a priority?

Watching the coverage as another reporter who was covering those bills on a different beat, it was stark seeing the medical care that I need to live get lumped into what reporters often use as shorthand—whether it be like “culture war,” “anti-woke.” Sometimes I’d see it get lumped into “DEI,” which to me is not accurate. I’d see it get lumped into conversations about abortion. It was often lumped into [issues of] health care, LGBTQ acronyms. It was surprising how few reporters asked about this language.

When I look back on my conversations with my colleagues in the press, those who I’ve worked next to quite often, the conversations about this language usually went something along the lines of, “Either readers don’t care about it, or it’s just another poison pill.” I think often reporters are trained to think on the Hill, like, “Is this going to be law today? Well, no. Then I’m not going to spend my time on it.” It’s a heavily reactive kind of journalism today.

A sliver of a sliver of the American people is being targeted explicitly, and I think there’s just not a prior frame of reference. People thought it wasn’t going to be law, and so they didn’t cover it. Although I don’t really know if that was the case. No one was asking, “Is this going to become law?”

I think in journalism overall, but especially on the Hill, because we interact with lawmakers of both parties on a daily basis, there is a desire to seem “objective” or “neutral.” How do you think that affects how reporters talk about or cover trans issues?

When I became a climate journalist, I was drawn to that field because it was something so pressing, rooted in science, that had been over decades politicized to the point where one side of a political argument—at least when I started in congressional journalism, and in policy journalism—was spending a lot of time arguing that the science wasn’t sound or that the claims made about man-made climate change were somehow questionable. Over time, we as an industry have come to grips with the fact that that’s the product of a number of actors, a number of campaigns, industry-funded and also politically motivated, to somehow convince at least some percentage of the population that the science can be questioned. And we learned how to cover it that way.

I’ve spent a lot of time and continue to spend a lot of time talking to other reporters and editors about what story ideas are out there. I think that’s something that should be happening in more newsrooms on this topic. And what I’ve found is a—reluctance would be putting it mildly to the point of absurdity—an outright refusal, I would say, in some newsrooms, to write about the science behind this medical care the way that doctors and scientists talk about it. And I think that that’s happening because there is a fear of offending readers that don’t like trans people. And I know this firsthand, because I myself have heard that from people in our industry.

I’m glad you mentioned that comparison to climate journalism. I thought that was a really interesting comparison that you made in your essay. And I’m curious to know more why you think it’s so difficult to incorporate that into health reporting. I know you say people are afraid of offending those who oppose trans rights. But do you think that this, like climate journalism, just will take time? Or is this something that you’re less optimistic that people will come around to the science of?

It’s not even a question of optimism. Mother Jones recently reported … on the shadow campaign against this medical care. This is a dedicated, concentrated, well-thought-out, potentially global campaign to take away this medical care for ideological reasons that do not have any favor for making sure that people who need it survive.

I would like to say that I am optimistic that journalists will wake up to these facts. I would like to say that with training and with resources, reporters will cover this in a way that’s authoritative. But they need to overcome that fear, and that hesitation to deal with the existence of trans people as though it is fact. And I think the longer that it pervades, the less likely it is for it to improve. Because this industry’s crumbling. It’s sad to see, as a member of it. At a time when you need to be assigning people to a new story, do newsrooms have the resources to take it on?

I think there’s a huge story in this. Some day, some intrepid reporter is going to dive into it and win a Pulitzer Prize—or, like, seven of them—and I think that that day that person will be looked at as though they were a genius, and all they did was look at the pretty easy-to-find facts around them. When I was at Politico, I wrote at least four stories, investigative stories about the anti-trans movement, on top of the work that I did in climate. I did it because I think that there is a need for those of us who are trans in the press corps to use the privilege that we do have to at least improve somewhat—whatever margin it can be—the misinformation out there, and the lack of proper source identification out there, the lack of context. But I left Politico, and I think that says a lot. I left the Hill, and I think that says a lot. I think people need to recognize that if they’re not careful, there won’t be people around to help cover this better because all of us will be gone. Like the Lorax.

What’s next for you?

Stay tuned. I am staying in climate journalism. I have a really cool thing I’m doing that I can’t talk about right now. But stay tuned, keep eyes peeled. I’ve never been more excited. And on top of journalism, I am literally talking to you inside of my first-ever touring van rental because I’m about to go play a couple weeks of dates with my band, Ekko Astral. I’m really excited about that.

What I’m reading

Wartime emissions rage, but no one’s counting them, by Chelsea Harvey in E&E News

The ‘Appeal to Heaven’ flag is all over Capitol Hill, even as it becomes more controversial, by Haley Byrd Wilt in NOTUS

Once a beauty contest, Miss Subways is now a campy, voicy extravaganza, by Haidee Chu in The City

What Europe fears, by McKay Coppins in The Atlantic

How Imagine Dragons became the sound of gaming culture, by Gene Park in The Washington Post

‘We are the world power’: How Joe Biden leads, by Massimo Calabresi in Time

Is sports gambling a public health crisis? by Katrina Vanden Heuvel in The Nation

Pet of the week

Want to have your pet included at the bottom of the next newsletter? Email me: gsegers@tnr.com.

This week’s featured pet is Big Silver, submitted by The New Republic’s own Laura Marsh. Big Silver’s age and gender are unknown, although it has lived in Laura’s koi pond for two years. Big Silver is a butterfly koi—so called because of its butterfly-shaped wings—who enjoys eating mosquitoes and swimming under the ice in the winter.