Des Moines

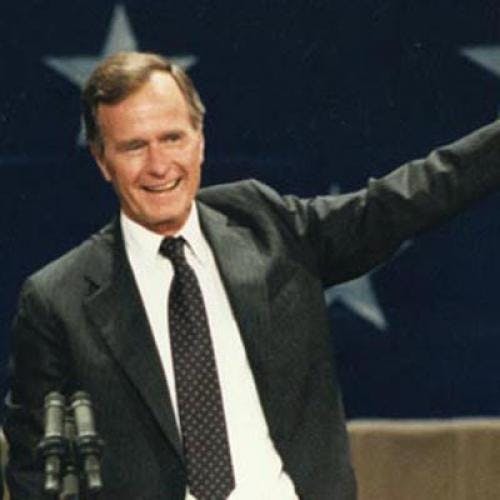

You already know—or will shortly—who won the Republican caucuses in Iowa on January 21. Writing beforehand, I don't. But if it turns out that former CIA director George Bush has scored a fantastic upset over Ronald Reagan, or if Bush finishes a close second—which would also be a remarkable come-from-behind achievement—I think a single piece of paper might prove to have been the decisive factor.

Rich Bond, Bush's 29-year-old state campaign director, calculated early this month that when evening fell on January 21, Republicans in Iowa might still be confused about exactly where to go at 8 p.m. to cast their presidential preference votes. The 2531 precinct caucuses are held in 1J36 locations around the state—some precincts double up in the same place—and the caucus sites are often not the same as a voter's normal election-day polling place. They might be in a local school, lodge hall, church basement, or in somebody's living room. In fact, 678 of the Republican caucuses will take place in private homes, Iowa law requires that precinct locations be listed in local newspapers before the caucuses, but Bond figured that voters might miss the notice, mislay the paper, or, most likely, be uncertain what precinct they live in. So Rich Bond devised a “caucus kit” to be mailed out to every person who had been identified as a George Bush supporter, telling him or her on one sheet exactly where to go on January 21, and also listing the names of friends and neighbors who are fellow Bush supporters whom they might call for a ride.

BUSH’S KITS WERE going out two weeks before the election, and last week volunteers were telephoning the recipients to ask if they got them, if they could be depended upon to show up on the 21st, and whom they would bring with them. All the names were put on a file card, and on January 19, in a final telephone blitz, the campaign planned to call everyone back for a reminder and final urging to turn out for sure. By caucus day, Bond said, every Bush supporter will have been called or personally contacted four times. By contrast, the Reagan campaign has been planning to phone its supporters twice—once to identify him or her as pro-Reagan, and once more to tell him or her where to go on the 21st, Not only were the Reagan contacts less numerous, but they were not as early. Reagan workers were still scrambling as late as the last week before the caucuses to compile lists of the locations, and they had no plans to send each of their supporters a piece of paper telling him or her where to be.

Bush's get-out-the-vote effort is in keeping with his whole campaign effort in Iowa—fast, thorough, intensive, and imaginative, Reagan's, by contrast, has been late, slow, and cautious. In June and July the Reagan campaign made 10,000 sample phone calls to Iowa. Republicans, found 3500 who would state a presidential preference, and delightedly discovered that 90 percent said they were for Reagan, Reagan’s confidence was bolstered by a Des Moines Register poll in August showing that 48 percent of Iowa Republicans favored him for president, as against 23 percent for his nearest rival, Tennessee senator Howard Baker. In that poll, Bush got one percent.

The Reagan campaign laid off for the summer and fall. Local Republican organizations held dozens of speech-and-chili suppers and fundraisers around the state at which not a single Reagan representative was present, even to pass out bumperstickers and campaign buttons. Bond, who arrived in the state in June, saw to it that a Bush representative was at them all. Often it was Bush himself or his wife, Barbara, who between them have visited 86 of Iowa's 99 counties. Bush spent 21 campaign days in Iowa in 1979, compared to 15 hours for Reagan, Such is Reagan's breadth of support, however, that an early December Des Moines Register poll showed him with 50 percent support among Iowa Republicans, to 12 percent for Bush, 11 percent for Baker, and 12 percent for John Connally.

Despite the statewide poll result, Reagan suffered a number of setbacks in the fall in straw votes held by county GOP organizations, and leading Reagan backers began to worry aloud that Bush might pull an upset unless Reagan got busy. In mid-December, the national organization sent out a Washington lawyer, Pete McPherson, to pull the Iowa organization into shape. Despite his efforts, Reagan by mid-January had county chairmen in place in just 80 of Iowa's counties, whereas Bush had all 99 covered in December, Bond figures that he has organizations in half the state's 2531 precincts, McPherson says only that Reagan is organized in “a substantial number.”

Nationally and in Iowa, the two campaigns have been operating on vastly different strategies. For Reagan, national campaign manager John Sears has designed a cautious, mistake-avoidance strategy that calls for the candidate to make a limited number of carefully choreographed appearances. Reporters are meant to be impressed with the size of Reagan crowds—indeed, he had 1500 the other week at a rally in Davenport, and sold out a 750-plate luncheon in Waterloo, Iowa—and with their enthusiasm, whipped along by bands, bunting, and balloons. Sears knows that national polls show Reagan with the solid backing of 45 to 50 percent of Republican voters. In Iowa in 1976, Reagan got 49 percent support in the caucuses against 51 for President Gerald Ford, Sears wants no screw-ups, and sees to it that the candidate's physical and intellectual energies are carefully husbanded. Reagan has been on the road about four days a week to primary and convention states, but he's limited to two or three events per day. Sears was willing to have Reagan suffer widespread criticism for his failure to participate in the January 7 Republican debate in Iowa, but at the same time he avoided a nationally televised error that might jeopardize his lead. At a Reagan rally there are never questions and answers from the audience. At the candidate's press conference there are questions, but rarely any definitive answers.

The Bush strategy is designed to bring the candidate from nowhere quickly—to achieve remarkable results in Iowa and New Hampshire that will make Bush, and not Howard Baker, the champion of GOP “moderates” and have Bush viewed as the final challenger to Reagan, In Iowa, Bush's aim is to hold Reagan to less than 40 percent of the vote and finish a strong second, well ahead of Baker and Connally. Whereas Reagan's aim in Iowa is to convert his broad-gauge popularity into a massive turnout on caucus night. Bush’s has been to establish intensive support among Republican regulars, get them to the caucuses, and pray for a huge snowstorm on the 21st that will keep Reaganites at home. Bush has managed to win impressive backing in the Iowa Republican establishment, A former GOP national chairman himself, he's being helped by another former chairperson, Mary Louise Smith, the grande dame of Iowa Republicanism, and by John McDonald, the state's Republican national committeeman. Of 297 elected county Republican leaders, 50 are for Bush, a high number considering that such people usually want to stay neutral in an intraparty fight. Of 85 Republican state legislators, 25 have endorsed Bush, as have both of Iowa's Republican congressmen.

Reagan's manager, McPherson, admits that Bush is in solid with the GOP establishment, “Of the first 25,000 people who go to the caucuses. Bush will probably have shaken hands with every last one,” he said. But McPherson says these people represent only country-club and charity-ball Republicans, and that Reagan's support lies among a vast working-class and middle-class group that votes Republican but has never been to a caucus before, in the belief they are smoke-filled meetings of professional pols, McPherson designed radio ads featuring Reagan saying that caucuses are nothing of the kind, just “neighborhood gatherings like your local PTA.” Late last week, McPherson was cheered by a long-range weather forecast predicting warmth and sun, uncommon stuff for Iowa in January, and very good for Reagan.

Bush's chances for an upset are complicated not only by the weather, but also by a last-minute drive by Howard Baker, who has no organization to speak of in Iowa, but is saturating the state with well-designed television ads that will cost him more than $100,000. The best of the ads shows Baker shouting down an Iranian student at a campaign rally and being given a standing ovation. Baker also has the advantage of the widespread knowledge that Iowa’s popular governor, Robert Ray, prefers him. Though Ray has not openly endorsed Baker, he arranged for two of his longstanding associates to take over the Baker effort in Iowa to bring it out of a slough. An effective campaigner. Baker has been blitzing the state during the final days of the campaign, telling audiences they ought to prove to the country that “you don't have to be unemployed for two years in order to be a candidate for President.” He is referring to George Bush.

The best news of all coming out of Iowa is that John Connally is going nowhere. Like Baker, he has no grassroots organization and is spending big money on advertising. But unlike Baker's, his ads are dull, showing a gentle John Connally, in denim jacket, talking about his Texas rancher’s natural empathy for the problems of Iowa farmers, Connally's true stripes have shown through, though. In one ad, he implied that Governor Ray had endorsed him—only to have Ray rebuke him for the falsehood. And the Iowa press has caught Connally deviating in one particular regard from his usual theme of get-the-government-off-our backs. Though Connally is true-blue for oil deregulation and lower taxes for industry, he is curiously against trucking deregulation, Iowans widely believe the reason is that Connally's chief Iowa fundraiser is John Ruan, who owns one of the biggest transport companies in the Midwest.

And now to predictions, foolish as it may be to make them. You should know that the Des Moines Register's final poll on January 11 showed that Reagan's support had plummeted from 50 percent in late November down to 26 percent, with 18 for Baker, 17 for Bush, and 10 for Connally, But the phrasing of the question was shoddy, seemingly reflecting the newspaper’s pique at Reagan for not participating in the debate it sponsored. No one in any camp believes that Reagan's support really has fallen so low. The conventional wisdom among state Republican officials and supporters of both Bush and Reagan is that Reagan will win, with around 40 percent; that Bush will be close behind in the 30s; and that Baker and Connally will be a distant third and fourth, followed by Senator Robert Dole and congressmen Phil Crane and John Anderson bringing up the rear in single-digit percentages. If the weather is good in Iowa on the 21st, I will stick with the conventional wisdom. If it snows hard, though, I will stick with Rich Bond's caucus kit, and the organizing it represents, and predict Bush to beat Reagan by a hair—32 percent to 29 percent, to be exact.

This article originally appeared in the January 26, 1980, issue of the magazine.