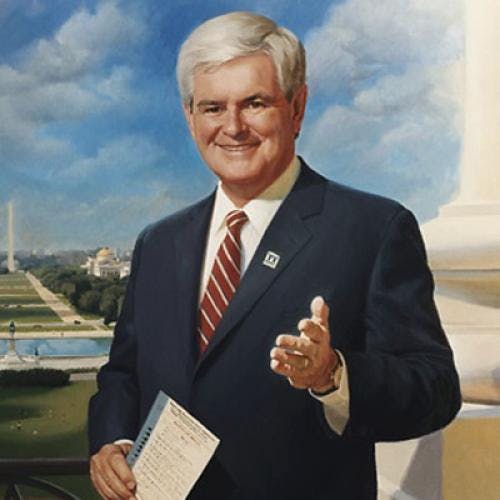

Last Friday, after more than a year of plotting in public and in private, hard-line conservatives finally got what they wanted: Speaker Newt Gingrich’s head. But, less than a day later, they were on the phones plotting again, this time against his all-but-certain successor, Louisiana Representative Bob Livingston. He had shown “an appalling lack of judgment,” David McIntosh, head of the Conservative Action Team, told The Washington Post, vowing to vote against him. Another GOP rebel told me Livingston is not “one of us” and warned: even if he wins, “he can’t lead without us.”

And so it goes in the Republican House. After Gingrich’s resignation last week, most people assumed the ceaseless infighting in the House Republican conference would at last abate. But, in fact, it may only get worse. With a mere six-seat majority, any band of dissidents—or “cannibals,” as Gingrich called them—can now thwart the legislative process. And. because of little-noticed internal procedural changes in Congress, the modern Speaker, as Gingrich discovered, has become all but powerless against them. “The real problem is not with the leadership,” says GOP Representative Mike Parker of Mississippi, who is retiring this year. “The real problem is with the followership.”

Indeed, the House of Representatives has increasingly become ungovernable for anyone—not just the much-maligned Gingrich. “It’s insane,” adds Parker. “I wouldn’t want to be in a foxhole with some of these guys.” Part of the trouble is the party’s familiar ideological division: The House GOP conference is split among Southern evangelicals, Northeastern moderates, and Western libertarians. Gingrich, aware that the Democrats’ fragmentation into unmanageable interest groups in the 1980s helped bring about their loss of control over Congress, tried to contain such factions in 1994 by defunding the myriad House caucuses. But dozens of new ones have since emerged, including the Missing and Exploited Children Caucus and the Pro-Family Caucus—all competing to achieve their narrow interests. The Republican conference is also split into two permanent warring camps: the Tuesday Lunch Bunch, a group of moderate Republicans, and McIntosh’s Conservative Action Team, a coalition of social conservatives. After four years of fighting, some members barely speak to one another. And, without the Contract with America, there is no overarching concept to bring them together on the House floor—or anywhere else.

Gingrich’s notorious character flaws, of course, exacerbated many of these divisions. His moods often swing as wildly as those of the conference itself. But the deeper explanation for Gingrich’s downfall is institutional, not characterological. Several congressional reforms, many of which Gingrich himself championed, along with the distortion of traditional House rules, have made it almost impossible to control the fractious body. (A similar transformation has occurred in the Senate, where the much more personable majority leader, Trent Lott, is also under siege from all sides.)

The most notable of these changes is the most obscure: a new rule limiting committee chairmen to only three terms and the speaker of the House to four. Slipped into a rules package in the first heady hours of the Republican revolution, it was supposed to contain lawmakers’ ambitions; instead, it has unleashed them. Livingston began campaigning for the speakership last summer only because his term as chairman of the powerful House Appropriations Committee was about to lapse. He had nowhere else to go but into retirement (which he also considered). Once be announced his candidacy, young members rushed to support his insurgency while launching their own: under the new system, they could climb the ladder more quickly by joining a coup than by stopping one. “The rule changes have created total chaos,” explains GOP Representative Joe Scarborough of Florida. They’re “the dumbest thing we’ve done,” adds Resources Committee Chairman Don Young of Alaska.

Even more destabilizing, though, are some members’ self-imposed term limits. While Congress never passed term-limit legislation, several crusading lawmakers have voluntarily adopted them. Now they constitute a kind of roving band of mercenaries who wander the House floor, looking for somebody to topple. They have no incentive to work within the system—and no fear of reprisals from the Speaker. “The best thing about it is you get to really piss off some very powerful Republican every six months,” Congressman Matt Salmon of Arizona told me earlier this year.

Not coincidentally, the first person to call for Gingrich’s ouster was Salmon, who participated in the coup attempt in 1997 and has vowed to serve no more than three terms in Washington. “Members with self-term limits make them even more inclined not to adjust to the system but to make the system adjust to them,” explains Barbara Sinclair, a congressional scholar at UCLA. And many rebels no longer settle for adjusting the system—they level it. Under traditional House rules, members are not supposed to use funding for approved federal programs to change public policy. Now they do it as a matter of routine, polluting appropriations bills with extraneous amendments that grind the legislative process to a halt. “One member can now almost shut down the government by himself,” says a senior GOP aide, “and no one can do anything to stop him”

While shifts within Congress have institutionalized volatility, shifts outside Congress have made it nearly impossible to contain it. In the past, the Speaker could keep upstarts in line by threatening to give them lousy committee assignments, remove their names from major legislation, or even banish them to a basement office. But now a House rebel doesn’t land on the Merchant Marine Committee. He lands on “Nightline.” And “Meet the Press.” And “Hardball.” And “Larry King Live.” Indeed, today’s political dynamic operates in reverse; it punishes loyal team players with anonymity; while rewarding upstarts with celebrity. And it sustains them with the same perks that once only the Speaker could dole out: fame, direct exposure to voters, and access to campaign money.

The failed coup attempt in 1997 did not end the careers of sophomore Republicans like Lindsey Graham and Joe Scarborough; it accelerated them. Despite Gingrich’s threats of retribution, they won reelection overwhelmingly and became conservative icons. Another coup plotter, Steve Largent of Oklahoma, is now a serious contender for House majority leader after only two terms in Congress. Not surprisingly, when Matt Salmon concluded he could no longer support Gingrich, he didn’t quietly pull the Speaker aside—he sent his message a la Ross Perot on “Larry King Live.” Less than 24 hours after Gingrich resigned, Salmon offered a postscript, in the form of an op-ed in The New York Times.

Gingrich’s one serious effort at exacting discipline actually succeeded only in demonstrating the impotence of the modern Speaker. In 1995, after a group of rebels bucked his order to vote in favor of ending the budget shutdown and reopen the government, Gingrich did what Joe Cannon, Sam Rayburn, or Tip O’Neill would have done in the same situation: he refused to attend their fund-raisers. Only it didn’t matter. The money poured in anyway, and the rebels were unrepentant. It only made him more popular, Mark Souder of Indiana told me at the time.

ALL OF THESE forces have created a permanent culture of insurrection. Gingrich, of course, recognized these historical changes from the outset, and he tried desperately to reinvent the speakership. He read Peter Drucker and Alvin Toffler. He tried to listen and learn. He removed the oak desk in his office and replaced it with couches—a symbolic gesture of his desire to play counselor rather than commander. “He is leading the revolution right out of the pages of my book,” business guru Mike Hammer, whose book Reengineering the Corporation sold more than two million copies, told me back in 1995. According to Toffler, Newt was a third-wave CEO, “flattening out the hierarchy” and “operating in smaller units and adhocracies.” Party-switching former Democrats like Billy Tauzin of Louisiana and Mike Parker, who had attacked their own party leaders for years, heralded the changes. “He has built a fluid power structure, involving all Republicans, that seems anarchist but really has a strong executive,” Tauzin told me at the time. “If the Democrats had adopted such a system [they] might still be in power.”

But, by the end of 1996, it was clear that Gingrich was not in control of the minifactions; they were in control of him. At a closed-door meeting just before the 1998 election, a band of conservatives pressured Gingrich to shift tactics and push harder for impeachment. “It reminded me of the government shutdown,” recalls GOP Representative Peter King of New York, a leader of the party’s Northeastern wing. “They were all screaming and cheering. It was nuts.”

Now, into this pandemonium steps two-decade House veteran Bob Livingston, an institutionalist whose ancestors were present at the signing of the Declaration of Independence. A gifted politician, his allies insist he will create order the old-fashioned way: doling out favors, controlling committee assignments, punishing defectors. Even Democrats like David Obey predict that Livingston has the experience to make the House “much less cannibalistic.”

But some of the cannibals are already salivating. McIntosh, who tormented Livingston by clogging up the appropriations process with riders and repeatedly threatening to shut down the government, recently labeled the Speaker-in-waiting “an old-style-pork-caucus kind of guy.” Other rebels say they will press Livingston just as hard as they hounded Gingrich, and the party’s razor-thin majority means they have even more power to do so. “There will only be more bloodshed,” says Parker.

INDEED, THERE IS already a precedent. In 1995, when freshman Republican Mark Neumann (who recently gave up his seat to rtm a losing Senate race in Wisconsin) refused to vote for a critical appropriations bill, Livingston tried to assert his authority— and kicked him off a critical subcommittee. “At the start of the new Congress…members pledged to work in support of the panel’s business,” Livingston said in a press release. “We have tried very hard to address Mr. Neumann’s concerns…We need conferees who can get the committee’s work done.”

Within minutes, however, Neumann’s classmates were rising up. And, by the end of the week, Neumann had not only forced his way back onto the subcommittee but also won a new spot on the Budget Committee—a double assignment virtually unheard of for a lowly freshman. Afterward, Livingston sounded as resigned as Gingrich did last week: “A press release that was sent from my office yesterday…incorrectly implied that at the start of the one-hundred-and-foruth Congress I had exacted the pledge of all members…to work in support of my agenda. This is a completely false statement.”

This article appeared in the November 30, 1998, issue of the magazine. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.