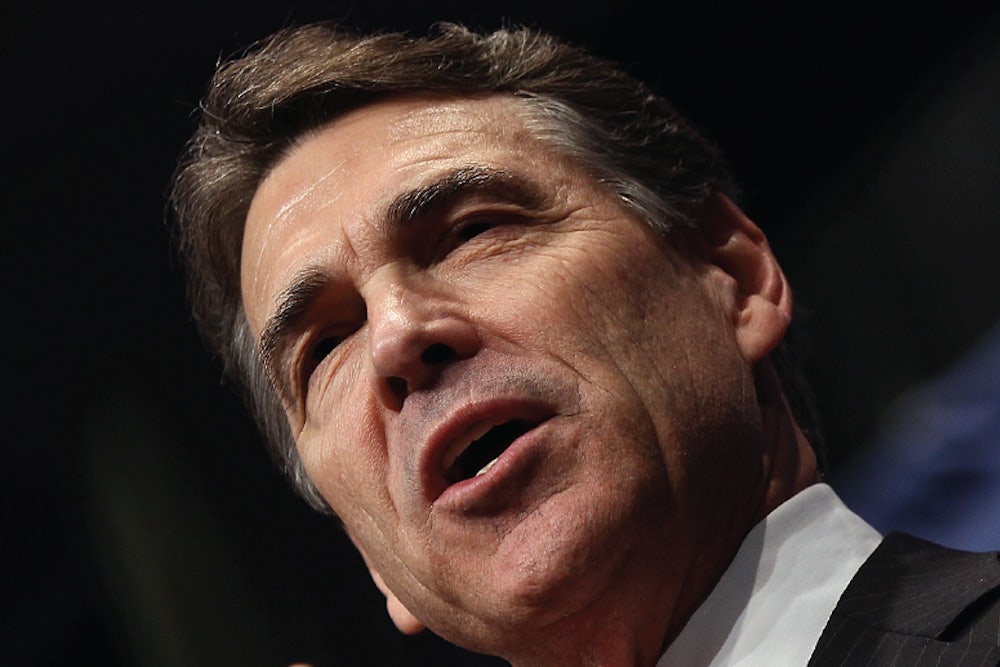

The Tea Party movement had not yet fully impinged on the nation’s consciousness when Rick Perry stepped to the podium outside Austin City Hall on April 15, 2009, to speak at a tax-day protest. Wearing a big “DON’T MESS WITH TEXAS” pin, a black baseball cap with a hunting ranch logo, and the collar of his coat turned up, Perry swayed as he spoke, as if trembling with fervor. The crowd of 1,000 roared as Perry invoked states’ rights and the Tenth Amendment’s protections against federal overreach. Following the speech, Perry spoke to reporters—and uttered a few sentences that would make national headlines for days and weeks to come. “We’ve got a great union,” he said. “There’s absolutely no reason to dissolve it. But, if Washington continues to thumb their nose at the American people, you know, who knows what might come out of that.”

Perry’s comments established him as the standard-bearer of anti-Washington sentiment months before the country as a whole began a rightward shift. It was “the first true love affair for the Tea Party,” Perry’s friend Bill Miller, a political consultant in Austin, told me. The remarks were also cause for glee among aides to Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, a more moderate Republican who was preparing to challenge Perry in the 2010 gubernatorial primary. Surely, Perry’s musings about secession would be fatal to his reelection. And, in fact, the Texas establishment, already leery of Perry, did edge further away from him—for one thing, he received not a single major newspaper endorsement in the 2010 primary. But it didn’t matter. The right-wing, anti-Washington wave Perry had picked up on kept building and swamped Hutchison, who lost by 20 percentage points.

That race, together with Perry’s 2010 call to arms, Fed Up! Our Fight to Save America from Washington—in which he referred to Social Security as a “Ponzi scheme”—sealed the image of him as a hardened ideologue driven by small-government orthodoxy. This amuses those in Texas who know Perry best. What was on display that day in April and in the months since, they say, was not Perry the ideologue but Perry the tactician—a politician skilled at picking up on shifts in the electorate and adapting himself to them. Perry, says Bill Allaway of the conservative Texas Taxpayers and Research Association, has a “knack for seeing where stuff is headed and thinking where he could be with respect to that.” The tax-day speech was an example of Perry “getting right in front of the parade,” says Miller. “He saw that this is where I need to be right now. And that’s just having good campaign judgment to do that.” Perry’s political guru, Dave Carney, basically said as much when I met with him in Austin, attributing his client’s prescience to the pleasure that Perry takes in being out among voters. “He listens, he looks you in the eye, and he gets a sense of where people are going,” Carney told me. “He has a very good sense of what’s going on.” Greg Hartman, a former Texas political strategist, marvels at Perry’s transformation since 2009. “The most amazing thing about Perry is that now that he’s jumped out there, people say he’s brash and caustic, but he built his career as lieutenant governor and governor by being pretty quiet. He’s not brash. This is a little bit of a new persona here.”

None of this is to say that Perry isn’t really a conservative. He most certainly is. Specifically, he’s the product of a West Texas political culture that Miller describes as a “sort of Confederate-based, anti-federalism, anti-telling-me-what-the hell-to-do kind of deal.” But Texans, it turns out, don’t tend to think about Perry in ideological terms. “I’m not sure you can ever ascribe a real philosophy to Perry,” says Tom Uher, a conservative Democrat who lived in the same Austin rental house as Perry when both were serving in the state legislature in the 1980s. “He can switch colors to whatever he needed to be.” Indeed, the deeper one looks into Perry’s past, the more it becomes clear that ideology is not a particularly useful way to explain his actions or his worldview. But, if political philosophy doesn’t really animate Perry, the question remains: What does?

RICK PERRY, NOW 61, grew up in Paint Creek, a tiny West Texas town in rural Haskell County. The area is not all that far west: It’s in the north-central part of the state, just east of the panhandle. But West Texas is defined less by longitude than by terrain—the huge, arid swath beyond Fort Worth. Rick’s father, Ray Perry, was a World War II tail gunner and a tenant farmer, leasing land for cotton, wheat, and cattle. Ray was on the county commission as a Democrat. Conservative “yellow dog” Democrats so dominated Haskell County that it did not hold a Republican primary for local offices until the 1990s.

Don Comedy, who grew up with Rick Perry and managed his campaigns for the legislature, recalls what the place was like: “In those early days, we were all poor, all struggling. When I was growing up, people didn’t know a single solitary person that didn’t have to work to get by … . There was sand blowing and drought. When there were sandstorms, I’d have to rake the sand off the cabinet and the table and sweep it up. It was so thick it would take a piece of cardboard to scrape it off.”

On Saturdays, Rick was with the Boy Scouts. The troop met at the home of farmer Gene Overton, an unusually committed troop leader: He took the boys to Dallas and to College Station, where they slept in empty cattle pens in the livestock pavilion. “We put a lot of gray hair on that old man,” says fellow scout Riley Couch. “We were just kids enjoying life, and we didn’t know too much about the world and worry about much.” Rick hardly stood out as a future leader. “Someone asked me once if we sat around talking about being governor,” Couch says. “No, I don’t think we even knew there was a governor.”

In 1968, Rick left for Texas A&M, then the scene of a social upheaval. Prior to 1965, it had been mandatory for students to receive military training through the Corps of Cadets. With that requirement dropped, a whole new crowd of students began enrolling at the school. The result, recalls Hartman, the former political strategist in Austin, was a “weird bicultural campus,” split between “typical college students” and Corps members. Perry, who was in the Corps, developed a reputation as a prankster and received terrible grades, but managed to get elected “yell leader,” a prestigious position roughly akin to cheerleader. His political training took other forms as well: One summer during college, both Perry and Couch sold Bibles in southeastern Missouri. “If you want a lesson in life,” says Couch, “you go door to door trying to sell something to somebody.”

After graduating in 1972, animal science degree in hand, Perry began a five-year stint in the Air Force, which included supply runs in Europe and the Middle East. By the late ’70s, he was back in Haskell County with his high school sweetheart, Anita Thigpen—a doctor’s daughter and former drum majorette whom he married in 1982. Rick helped his father with his farming, but not always to great success. A family that had hired Ray Perry to manage its cotton and wheat fields grew upset when they discovered after some time that Ray had been leaving the fields in Rick’s hands—and that they were overrun with weeds. When Letajo Howard, one of the owners, tried to talk to Rick about it, he told her he had a date to go bird-hunting and that she should take it up with his father. “We chided him about that and told his father he was not to farm for us anymore,” she told me.

Fred McClure, a close friend of Perry’s, says he could see political interest budding in him during the years after his return from the Air Force. McClure, then an aide to Republican Senator John Tower, met Perry when he came to Washington on his own in 1978 to check out the farmers’ protests that were dominating the city. A couple years later, McClure got Perry his first political appointment: He suggested that Governor Bill Clements, a Republican, put Perry on the Texas Real Estate Research Advisory Committee. “That was the beginning of my seeing him have these political sensitivities and antennae,” McClure says. “His decision to get involved in politics originally was a combination of believing he could do something that could have an impact and maybe the boredom of staying at home.”

In 1984, when the local state representative announced his retirement, Perry jumped. In the Democratic primary, Perry was able to fly his 1952 Super Cub around a district that took four hours to cross by car. Comedy, whose family ran the local newspaper, wrote the stump speeches; his most reliable laugh line was one that Perry still uses, in which he brags about having graduated in the top 10—in his high school class of 13. To get up to speed on legislative matters, Perry quizzed a local lawyer active in Democratic politics, Royce Adkins. On the day of the primary, Perry triumphed with 59 percent in a three-person field; the general election was uncontested. Having secured the seat, Perry made clear that he did not exactly have a big policy agenda. “I had not one piece of legislation I planned to carry,” he told the Abilene paper after the election.

Once in Austin, Perry made little effort to hide his lack of interest in the finer points of policy. Garry Mauro, then the Texas land commissioner, remembers coming to Perry to sponsor a piece of legislation and Perry cutting him off when he started to explain the bill in detail. “Don’t waste your time,” Perry said. “I wouldn’t understand it anyway. Just make sure you’re there to talk about it.” Recalling the incident today, Mauro says, “You at least have to give the guy credit for candidness.”

Yet Perry still managed to make his mark. By his second term, he had become one of the “pit bulls,” a group of young legislators, mostly sophomore conservative Democrats, who had been given seats on the appropriations committee and quickly set about trying to slash spending. “They decided early on they didn’t have to just sit there and listen,” says Allaway. Their cocksureness rankled veteran legislators, including Uher. “There were some who thought those pit bulls were cute,” Uher told me. “But they did not understand the appropriations process, the history of the agencies. The veterans would look on them, saying, ‘You’re here to turn the world upside down, but you don’t know.’ ”

Even among the pit bulls, Perry stood out. He was the handsome rancher who flew himself home at the end of every week, often offering a ride to Bob Hunter, a Republican from Abilene. That Perry had his eye on bigger things was confirmed for some of his colleagues when he showed up in his second term with a full set of corrective braces, which had the end result of enhancing his good looks. “Everybody who noticed his braces suspected that [it was a career move], but no one confirmed it,” says Steve Carriker, then a Democratic senator from West Texas.

Perry excelled in one area especially: The future governor “was very, very good at developing relationships with his peers,” recalls one veteran state Democrat. “All of those guys are still very much with Perry, very much a part of his political life, and all are making a living out of being with him.” He pointed as an example to one Perry pal, who, despite having been once voted the most liberal Democrat in the legislature, “now makes a living off of lobbying him.”

In 1988, Perry endorsed Al Gore for president. The decision looks understandable in retrospect, given that Gore was one of the more centrist (and Southern) candidates in that year’s Democratic field. But the veteran state Democrat was struck by how eager Perry was to take a lead role in the Gore effort, which has been downplayed in more recent accounts of the episode. The official co-chairs of the campaign in Texas were two older, prominent state Democrats, Bill Hobby and Jess Hay. But Perry and a few other young House reps got together and, with the elders’ permission, started calling themselves co-chairmen as well—with Perry flying them around the state on Gore’s behalf.

Yet, even as he was angling for status in his own party, Perry had caught the eye of those building the new GOP in Texas, notably a doughy savant by the name of Karl Rove. The state had been solidly Democratic for generations, but change was afoot, as Democrats became associated with Northern liberals like Jesse Jackson and Ted Kennedy. In 1983, Texas Congressman Phil Gramm had announced that he was switching parties. In 1989, with the coaxing of Rove, and with Gramm standing at his side, Perry announced he was doing the same in order to take on agriculture commissioner Jim Hightower, a darling of liberals and nemesis of Texas farmers. It was a bold move. “What the hell did I just do?” Perry muttered aloud after announcing the change, according to one Republican insider. In Austin, the switch only confirmed the sense that Perry was a striver. “Governor Perry is a really, really good politician,” Hartman, the former strategist, told me. “He understood where the state of Texas was going.”

For the race against Hightower, David Weeks, the TV whiz in Rove’s shop and a friend of Perry’s from West Texas, crafted gauzy spots featuring Perry in chaps and playing piano with his young son. “David is wonderful at capturing him and projecting him,” says Miller, the Austin consultant. “Rick’s his muse.” Weeks also produced an ad that showed images of flag-burners morphing into Hightower’s face. On Election Day, Perry eked out a win, 49 to 47 percent.

As commissioner, Perry set about scrapping Hightower’s regulations on pesticides and played up his bond with farmers, defending them against attacks from “food terrorists and stomach police.” But his anti-government stance only went so far: He sought big increases in his department’s budget and defended a state loan program for farmers against a critical audit.

Meanwhile, the state’s political shift toward the GOP was accelerating. When Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock, a Democrat, announced he would not seek reelection in 1998, Rove urged Perry to run in the hopes of putting a Republican in place to take over as governor if George W. Bush was elected president two years later. Perry was ready—even though it meant running against a good friend from A&M, Democrat John Sharp.

Rove couldn’t manage Perry’s race because Bush wanted him to focus on his reelection bid that year. Instead, Perry turned to Carney, an acerbic New Hampshirite who remains his strategist to this day. The two teams clashed over strategy: Rove and Bush demanded that Perry not go too negative, to help maintain the bipartisan aura that they wanted to carry into their upcoming run for president; Perry, already resentful of the Bush scion’s unearned elevation in Texas politics, chafed at the order, according to several people with knowledge of the campaign.

Sharp told me that running against Perry was like nothing he’d ever experienced. “You talk about focus—the man gets focused. Hell, we were getting up at five a.m. in the morning to go to breakfasts, and this guy was getting up at four a.m. and doing two breakfasts and then a luncheon,” he recalls. “If you run against Perry, you’d better bring your lunch because you’re not going to have much time to eat it.” Perry was distinctly less eager about one element of the campaign—the televised debate. At his urging, it was held in El Paso on a Friday night at the height of the high school football season. “El Paso on a Friday night during a football game and the time zones are different,” Sharp says. “How many people do you think watched that?”

Polls showed the race as a nail-biter. But, at the last minute, Perry received a $1.1 million loan from several top Republican donors, including Bill McMinn, a chemical executive, and James Leininger, a staunch social conservative and proponent of private-school vouchers who made his money manufacturing hospital beds. “That was the edge,” Sharp says. “Before the last week, our money-raising was just about equal, but in that last week he had twice the airtime. It was a big deal.” On Election Day 1998, Perry won with 50.4 percent, a far narrower margin than the one enjoyed by Bush and other Republicans on the ticket. (In an odd twist, Perry managed to lose his home county, where the shift toward the GOP had not fully taken hold.)

After the election, Perry set about retiring his debt by holding fund-raisers where lobbyists were asked to give $50,000 each, a more aggressive approach than Texas had seen before. He charted his own path in other ways, too. Among Bush’s proudest accomplishments as governor was the friendship he had cultivated with Democrats like Bullock and House Speaker Pete Laney. Every Wednesday during the legislative session, the trio would meet for breakfast. The tradition continued once Perry replaced Bullock—but the new lieutenant governor seemed to have little interest in the gatherings. Several people with knowledge of the breakfasts told me that, while Laney and Bush would chat, Perry would sit in near-total silence. Sometimes, to fill the time, he would file his nails.

AFTER BUSH WAS sworn in as president in 2001, Perry became governor. He quickly developed a reputation for blocking legislation, vetoing 82 bills on a single day in June 2001—an episode that became known as the “Father’s Day Massacre.” In a weak-governor state like Texas, the veto pen was an obvious way to let legislators know who was really in charge. Democrat Paul Sadler, a former representative from East Texas who is on friendly terms with Perry, recalls the day in 2001 when a Perry aide called to inform him, in grave tones, that the governor was vetoing a bill that Sadler in fact had little to do with. “He was sending me a message … but he didn’t realize it wasn’t mine,” Sadler says.

Perry’s penchant for vetoes continued even after Republicans took control of the Texas House in 2002. In some cases, he was objecting to legislative compromises he found unacceptable; but, in other cases, his priorities were simply out of step with Republicans in the legislature.

How could a conservative Republican governor find himself so at odds with a legislature controlled by his own party? It wasn’t for a lack of partisanship—Perry campaigned far more aggressively for state Republicans than Bush had done. The best explanation was that Perry often seemed more driven by personal priorities than ideological ones. His failed highway and rail plan, the Trans-Texas Corridor Initiative, was derided by legislators of both parties as a boondoggle that would have required a massive land grab. But the project also would have benefited three highway contractors who had contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to Perry. The governor’s attempt to mandate that Texas girls receive a vaccine for HPV, so seemingly at odds with Perry’s social conservatism, came at a time when his former chief of staff—one of five Perry chiefs of staff to also serve as lobbyists—was lobbying for Merck, the vaccine’s manufacturer. (Merck contributed $5,000 to Perry during the vaccine discussions and nearly $30,000 over the past decade.)

There were plenty of other moments where Perry’s actions seemed to align with the needs of his very successful campaign account. (By the 2006 cycle, Perry had 85 donors giving at least $25,000, double Bush’s total from eight years earlier.) In 1999, Perry’s first year as lieutenant governor, an e-mail from a Dallas insurance executive surfaced claiming that, by offering a $25,000 contribution, a lobbyist had convinced Perry against convening a Senate committee on insurance deregulation; shortly after the e-mail was sent, Perry received $19,000 at an insurance industry fund-raiser. In 2008, Perry requested a waiver from federal ethanol mandates; a month later, an East Texas poultry producer who was pressing for the waiver to keep feed costs lower contributed $25,000 to Perry. Earlier this year, momentum grew for a bill restricting texting while driving, authored by former Republican House Speaker Tom Craddick. Perry vetoed the bill in June, following a surge in contributions from telecom companies—especially Dallas-based AT&T, whose PAC has given the governor more than $500,000, including $100,000 last year. (“This is a big deal to AT&T. We live in our cars here,” says Garnet Coleman, a Democratic state representative from Houston.) In August, after much debate over whether to turn millions of Medicaid beneficiaries over to managed care companies, Texas awarded a $1 billion Medicaid contract to the HMO Centene—whose PAC has given Perry $45,000 since 2006.

When it came to appointments to Texas’s 270 boards, commissions, and agencies, the pattern was no different. Texas governors have historically made full use of the power of patronage, but Perry has done so with particular zeal. A report last year by Texans for Public Justice, a watchdog group, found that he had received contributions from nearly two-thirds of the 155 state university regents he had appointed—$6 million in all. Leininger, who helped arrange the 1998 loan to Perry’s campaign that may have allowed him to barely defeat Sharp, continued to support Perry, giving him $239,000 over the decade; meanwhile, Perry appointed former top employees of Leininger’s hospital-bed company—in which Perry’s personal investment during the ’90s resulted in a $38,000 gain—to the Texas Board of Health, as chair of the influential Texas Workforce Commission, and as head of the nonprofit that oversees the state’s faith-based grant-making. In another case, Perry created a whole new government body, the Texas Residential Construction Commission, to allow building contractors to self-regulate rather than fight claims in court. Among those pushing hardest for the new board was the homebuilder Bob Perry (no relation), who gave the governor $175,000 in the two years prior to the board’s creation in 2003 and whose own corporate counsel was given one of the seats on it. (Bob Perry’s other priority has been fighting immigration restrictions that could drive up his labor costs—which some Texans point to as one possible explanation for Rick Perry’s moderate stance on illegal immigration.)

Perry’s seeming emphasis on cultivating allies rather than advancing legislation means he has left an oddly shallow policy imprint—especially given that he is the longest serving governor in Texas history. He has presided over few major reforms other than a sweeping tort overhaul and a much-praised repair of the state’s juvenile justice system. “What does it say if your governor’s clearest role is in vetoing bills and not passing them, in a legislature that’s Republican dominated?” asks Kirk Watson, a Democratic state senator from Austin. Here, many Texans draw a contrast to Bush, who, despite facing a Democratic legislature, managed to implement more significant reforms, notably in education. “Bush’s focus was on what’s good for Texas,” says one senior state Democrat. “Perry’s was a little more on what’s good for Perry.”

BUT PERRY IS NOT running on his legislative legacy; he is running on his state’s impressive record of job creation. Economists are quick to point out the structural explanations for these numbers—the oil and gas boom, the state’s good fortune in escaping the worst of the housing bubble. Perry can point to one area, however, where he took direct action to create jobs: the two economic development funds he established. Most states use incentives to lure companies, but few toss out as much public money or do so with as little oversight as Texas. There is the Enterprise Fund, which Perry created with money from the state’s rainy day fund in 2003 to serve as a “deal-closing” mechanism for companies considering moving to Texas. And there is the Emerging Technology Fund, created two years later as a sort of venture-capital fund for Texas start-ups. Awards from both funds require only the approval of Perry, the lieutenant governor, and the House speaker; for the technology fund, Perry added a 17-member advisory council, appointed by him.

Together, the funds have distributed more than $800 million. By far, the two largest awards were to ventures associated with Texas A&M. While in Texas, I traveled to College Station to visit the one that is already up and running, the Texas Institute for Genomic Medicine (tigm). In 2005, Perry launched the institute with $50 million from the Enterprise Fund. Most of the money went toward buying mouse stem cells and software from a biotech firm called Lexicon Genetics. McMinn, who along with Leininger had contributed to the $1.1 million loan during Perry’s 1998 campaign, was an investor in Lexicon. And the Houston Chronicle would later report that he and another Lexicon investor, a former energy executive who now owns the Houston Texans, had each given Perry’s campaign account $25,000 a few weeks before the award was announced.

When I got to campus, the official gatekeepers at Texas A&M were unresponsive, so I went straight to my destination. The institute sits in a nondescript building behind the veterinary school; some cows were grazing in an adjacent field. As luck would have it, the lab’s director, Ben Morpurgo, was outside on a cigarette break, and he welcomed me in for a tour of the building, where a dozen big freezers hold embryonic stem cells culled from mice that are kept in 1,000 cages. Morpurgo, a genial fellow who had previously worked as a crocodile farmer in Israel and Ethiopia, was apologetic about the small size of the operation—it has ten employees, a tiny fraction of the 5,000 jobs Perry said the venture would eventually produce. “All the work we generate around here, on a lot of these things, it’s hard to put a dollar sign on it,” Morpurgo said. “But you need to look at the overall impact.”

That argument hasn’t been persuasive to many at A&M, who regard the institute as a bit of an embarrassment. In 2008, it was the subject of a scathing audit, and, in early 2009, the university’s president, Elsa Murano, declared that A&M was spending $2 million per year “to help TIGM continue to operate in spite of heavy financial losses.” A few months later, amid a growing dispute over the institute and other research funding, the Perry-appointed board of regents forced Murano to resign.

In 2009, Perry announced another $50 million grant, this time from the tech fund, to create the National Center for Therapeutics Manufacturing, which would seek to turn A&M into a hub of vaccine development. A year earlier, the A&M system had entered into an agreement to develop vaccines with a therapeutics manufacturing firm called Introgen; this put the firm in a position to benefit from the new center. Introgen’s founder, David Nance, is a close friend of Perry’s. He contributed $100,000 to Perry over the decade, he had previously served on the advisory committee of the tech fund awarding the $50 million, and Perry’s son, Griffin, owned Introgen stock between 2001 and 2004.

Introgen had its main drug rejected by the FDA and declared bankruptcy shortly before the $50 million award, but Nance continued to do well by the state. In 2010, the tech fund awarded $4.5 million to his next venture, Convergen, even after a review panel rejected the application. The fund paid Nance’s daughter $70,000 for promotional work, and several fund employees went to work with Nance. Perry also provided $1.9 million in federal funds to a separate Nance venture, Innovate Texas, founded in 2008 as a sort of clearinghouse for Texas tech firms. The outfit paid Nance a six-figure salary. It is now defunct. I was unable to find any trace of Nance—his name is still on the directory at his gated community outside Austin, but the line has gone dead. Meanwhile, the National Center for Therapeutics Manufacturing is nearing completion, a gleaming building not far from the genomic institute on A&M’s campus.

PERRY’S ENTHUSIASM for the job-creation funds is driven in part by his competitive spirit and well-established Texas chauvinism. He decided to launch the Enterprise Fund in 2003 after nearly losing out on a bid to bring Toyota to San Antonio, because he lacked the money to close the deal. In announcing the awards, his rhetoric verges on triumphalist, particularly if it involves beating a college football rival like Oklahoma. “It’s a little unusual to trash talk in our business,” says Jim Clinton, the former head of the Southern Growth Policies Board. “It’s not what you see most of the time.”

But skeptics see another possible explanation for Perry’s support of industrial policy: the multiple ways in which this approach appears to have benefited him. A Dallas Morning News report in 2010 estimated that $16 million from the Emerging Technology Fund had gone to firms backed by major Perry donors—including $4.75 million that went to two firms backed by Leininger. Often, the dynamic seemed quite obvious: After Joe Sanderson received a $500,000 Enterprise Fund grant to build a poultry plant in Waco in 2006, he gave Perry $25,000. More complicated was the case of Sino Swearingen Aircraft, which received a $2.5 million grant in 2006. The company rescinded its request for the money after announcing major layoffs, but that was not the end of the story: The Morning News reported in 2010 that among the company’s main investors was Doug Jaffe, the owner of Horseshoe Bay Resort near Austin. The resort is the site of one of Perry’s several highly lucrative land deals, which are the primary reason why the former farmer and career government employee is now a wealthy man. Perry bought a small parcel there in 2001 from his friend Troy* Fraser, a state senator, for about $300,000. In 2007, one year after the award to Sino Swearingen, he sold the parcel for $1.15 million to Jaffe’s longtime business partner, Alan Moffatt, a British national whom the U.K. government investigated in connection with arms shipments to Africa for use in the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Moffatt was never charged. A resort official told me that Moffatt had taken the initiative in reaching out to Perry, without Jaffe’s intervention.

But, even in cases where Perry himself did not seem to benefit, there were often questions about whether the money was well-spent. When I was in Texas, I went looking for the Texas Energy Center in Sugar Land, the Houston suburb made famous by its favorite son, Tom DeLay. The center—a public-private consortium for research and innovation in clean-coal technology, deep-sea drilling, and other areas—was formed in 2003. Its goal was clear: to attract billions in federal funding with the help of DeLay and Washington lobbyists hired by Perry’s administration. The state initially awarded the center more than $30 million. But the federal largesse never came through, and the Enterprise Fund grant was cut to $3.6 million, to be used as incentives for energy firms in the area. Perry made the award official with a 2004 visit to the Sugar Land office of the Greater Fort Bend Economic Development Council, one of the consortium’s members, housed inside the glass tower of the Fluor Corporation. Today, the Perry administration lists the Texas Energy Center as a going concern that has nearly reached its target of 1,500 jobs and resulted in $20 million in capital investment.

There’s just one problem: The Texas Energy Center no longer exists—at least not physically. The address listed on its tax forms is the address of the Fort Bend Economic Development Council, inside the Fluor tower. I arrived there late one Friday morning and asked for the Texas Energy Center. The secretary said: “Oh, it’s not here. It’s across the street. But there’s nothing there now. Jeff handles it here.” Jeff Wiley, the council’s president, would be out playing golf the rest of the day, she said. I went to the building across the street and asked for directions from an aide in the office of DeLay’s successor, which happened to be in the same building. She had not heard of the Texas Energy Center. But then I found its former haunt, a small vacant office space upstairs with a sign on an interior wall—the only mark of the center’s brief existence.

Later, I got Wiley on the phone. There has never been any $20 million investment, he said. The center survives only on paper, sustained by Wiley, who, for a cut of the $3.6 million, has filed the center’s tax forms and kept a tally of the jobs that have been “created” by the state’s money at local energy companies. I asked him how this worked—how, for instance, was the Texas Energy Center responsible for the 600 jobs attributed to EMS Pipeline Services, a company spun off from the rubble of Enron? Wiley said he would have to check the paperwork to see what had been reported to the state. He called back and said that the man who helped launch EMS had been one of the few people originally on staff at the Texas Energy Center, which Wiley said justified claiming the 600 jobs for the barely existing center.

In at least one instance, this charade went too far: In 2006, a Sugar Land city official protested to Wiley that, while it was one thing to quietly claim the job totals from a Bechtel venture in town, it was not “appropriate or honest” to assert in a press release that the Texas Energy Center had played a role. “There is a clear difference between qualifying jobs to meet the [Energy Center’s] contractual requirement with the state and actively seeking to create a perception of [it] as an active, successful, going concern,” wrote the official, according to Fort Bend Now, a local news website. In this case, reality prevailed, and Wiley declined to count the Bechtel jobs.

As for those cases where the funds have led to jobs in Texas, there has sometimes been bipartisan grumbling that many of the companies getting the cash would have come to Texas anyway. Citgo more or less admitted as much in 2004, when it got $5 million for moving from Tulsa but said that the move was a “strategic decision” driven by the need to be closer to its refineries in Texas and Louisiana. And, in 2005, the CEO of Hilmar Cheese, which got $7.5 million to move to the Panhandle, declared that its primary motivation was to avoid California’s tougher environmental regulations.

“To create these funds is a very un-conservative thing to do,” Southern Methodist University economist Mike Davis told me. In Austin, I asked Perry’s staff: Don’t both funds represent the sort of “picking winners and losers” that conservatives accuse Barack Obama of engaging in? Not so, they argued. “As I think the governor’s made clear, there are things the states can do that the federal government should not do,” said Ray Sullivan, his spokesman.

There is also the TexasOne Foundation, which Perry created in 2003 to pay for state marketing efforts. TexasOne’s model is simple: Businessmen cut checks in exchange for access to Perry, with the money going toward promoting the state at conferences or in the media as a business destination. The top rate of $50,000 per year earns an executive the right to go quail hunting with Perry and attend events like the Super Bowl, Rose Bowl, and Final Four. The foundation, with a $2 million annual budget, has paid for several of Perry’s trips abroad. (In one case, a 2009 trip to Israel where he received the Defender of Jerusalem Award, Perry traveled on the jet of highway contractor Doug Pitcock, an in-kind donation of $180,000.) Massey Villarreal, a Houston military logistics contractor who was the first president of TexasOne, told me the foundation served the state because executives liked to rub shoulders with the governor before making a big investment in Texas. “It’s putting icing on the cake,” he says. “These are people who think, ‘I’d like someone to show me a little love.’ ”

Perry’s opponents in Texas have tried dutifully to make something of these donations and expenditures and revelations as they’ve been dredged up by the more dogged elements of the local media. But Perry has been able to dismiss the press with a wave. Part of this may be due to sheer apathy. “Maybe it’s gotten to the point where people don’t like it, but they just think that’s how it works,” says Chris Bell, a former Democratic congressman who finished second to Perry in a four-person field in 2006. Part of it may be due to the fractured nature of the huge state: If a story appears in one of its 22 media markets, it may not be picked up in the others. And much of it is due to the exceedingly friendly landscape in which Perry has been operating. He has prospered by appealing to the sliver of Republicans who turn out reliably in primaries and then holding on in general elections, where he typically gets fewer votes than others on the GOP ticket but is still able to win. For his base, finger-wagging stories in the papers are hardly a detriment; Perry’s pollster has tested how Republican voters weigh newspaper endorsements and has found they actually hold them against candidates.

On the national stage, Perry’s new rivals have just started testing whether questions about his record in Texas will resonate with the GOP electorate. Michele Bachmann has invoked “crony capitalism” in criticizing Perry’s dealings with Merck, and Mitt Romney has attempted to cast Perry as a “career politician.” There is certainly plenty of fodder for these attacks. What no one knows is whether Republican voters are in a mood to care.

PERRY’S CAMPAIGN staff had barely moved into his campaign headquarters on Austin’s Congress Avenue, a few blocks from the majestic capitol, when I dropped by in early September. Deliverymen were wheeling in computer boxes; a lone campaign sign hung on the divider behind the front desk.

Jump-starting a presidential campaign is daunting, but Perry has a crucial advantage: an unusually cohesive team accumulated over two decades. “His Aggie and military background places a lot of weight on familiarity and loyalty,” explains Sullivan, who has been with Perry since 1998. “But, first and foremost, the group has been highly successful, and why mess with success?” At the team’s center is Carney, who keeps a low profile, shares Perry’s distaste for Washington, and is deeply committed to his boss. “He’s a fun guy to work for,” Carney told me at the campaign office, bare feet poking out of his shoes and his hands crossed over his considerable girth. “He’s got his sense of principle; he’s very loyal and very authentic.”

Carney’s skills as a tactician are legendary. In 2006, he invited four political scientists to run experiments during Perry’s campaign to test the effects of TV ads, direct mail, robocalls, and candidate appearances. One of the academics, Columbia’s Donald Green, told me that the experiments were not without risk, since they entailed withholding ads and other investments from much of the state. The findings were fascinating: Ads, direct mail, and robocalls had little impact, which led Carney to adopt an Obamaesque grassroots approach, with a heavy social-media component, for the 2010 campaign. “He’s willing to learn,” Green says of Carney. “He’s interested in trying new things, in seeing what works.” Laconic as Carney is, Green added, he is running the show: “He’s got an interesting blend of irascible and irreverent quarterback style. It’s interesting to see how much they defer to him. He’s in control.”

Also on the core team are Perry’s policy adviser, Deirdre Delisi, a no-nonsense former chief of staff, and his longtime pollster, Mike Baselice, who, according to Allaway, is “really good at figuring out what people are talking about” and with whom Perry likes to “spend a lot of time just talking about where stuff is headed.” Serving in an unofficial capacity are several of the original pit bulls, including Cliff Johnson, an East Texan who bookended lobbying work around a stint as a senior adviser to Perry.

Then there is Perry’s former chief of staff Mike Toomey, also a legislator in the ’80s—a Republican from the outset, unlike most of the other Perry pals—and the Merck lobbyist during the HPV controversy. He is a man who is “totally focused on what he is working on” and “doesn’t like opposition,” says Allaway. Miller, the consultant, says Toomey has a hidden lighter side: “He has a good sense of humor, but he never lets you see it because he likes being the dark figure.” Toomey is running a “super PAC” that aims to raise $55 million to back Perry. By law, it must not coordinate with the campaign.

While I was in Austin, I asked Sullivan: Why was his boss running for president, when he has said so often that what matters most in a federalist system is state government? (“Being the governor of a state like Texas, or for that matter, Oklahoma or New Mexico, is a more pivotal job in the future” than being president, he said last year.) Sullivan replied that Perry wanted to “use his record and philosophy of job creation to improve” the economy and “to reduce the scope and size of government that has gotten too big and intrusive.” Miller, the consultant, said there should be no doubt on that last point: “By God, I can tell you he will veto the shit out of spending bills.”

But these are ideological motivations. What seems to have spurred Perry most in his career is the business of politics: ladder-climbing, deal-making, campaigning, and, most of all, winning. Sometime in the past few months, it seems, he decided that he saw an opening for the final rung on the ladder. Already, there are ill-concealed whispers in the national Republican establishment that this one will prove too big a reach. Of course, they were saying similar things just a couple of years ago, when the Bush network and many other country-club Republicans lined up with Kay Bailey Hutchison against the man in the black baseball cap and the “DON’T MESS WITH TEXAS” button.

Alec MacGillis is a senior editor at The New Republic. This article appeared in the October 20, 2011, issue of the magazine.

*This piece has been corrected. The name of the Texas state senator is Troy Fraser, not Tony Fraser. We regret the error.