White House Watch

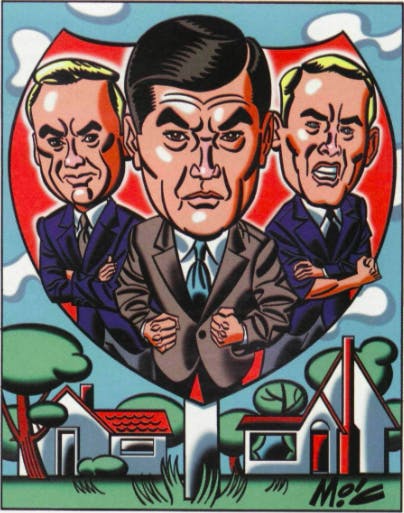

It’s not often that the White House holds a press conference to announce a demotion. But that’s what happened on October 9, when Tom Ridge, President Bush’s new homeland security adviser, and Condoleezza Rice, his national security adviser, introduced the administration’s newest anti-terrorism staffers. At a sterile ceremony in the fourth-floor briefing room of the Old Executive Office Building, Ridge and Rice announced that Richard Clarke, a pale, gray-haired man sitting on stage in an ill-fitting suit, would be the special assistant to the president for cyberspace security. It’s an important job, and insiders say Clarke wanted it. But it’s also a step down: For the last three years Clarke has held the more exalted title of National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection, and Counter-Terrorism—America’s terrorism czar. Sitting next to Clarke at the ceremony was the new czar, Wayne A. Downing, a retired four-star general who will report to both Ridge and Rice and hold the rank of deputy national security adviser. The shift from Clarke, the bureaucratic insider, to Downing, the Army general, signals something important: The war on terrorism will no longer be directed by people who specialize in politics; it will be directed by people who specialize in war.

For almost three decades Clarke mastered official Washington. What he didn’t master was counterterrorism. His first brush with notoriety came in 1986 when, as one of the State Department’s top intelligence officers, he hatched a bizarre scheme to incite a coup against Muammar Qaddafi in retaliation for the Libyan strongman’s support of terrorism. Clarke’s plan called for American planes to produce a wave of sonic booms over Libyan airspace while empty rafts washed ashore—not to attack, but to create the effect of an attack, which would spur Qaddafi’s enemies to move against him. The plan became public, was scrapped, and created a small scandal for the Reagan White House. Then, in 1992, Clarke’s State Department career abruptly ended when the inspector general accused him of failing to stop illegal transfers of sensitive U.S. military technology to China. Clarke strongly denied the accusations but fled State and landed at the National Security Council.

Things didn’t go much better there. In 1993 he oversaw Somalia policy during the American intervention, the greatest military debacle of the 1990s. Clarke was also in the middle of the botched effort to get Osama bin Laden in 1996, when the Clinton administration rejected—as The Washington Post recently revealed--a Sudanese offer to hand him over. Then, in 1998, he played a key role in the Clinton administration’s misguided retaliation for the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, which targeted bin Laden’s terrorist camps in Afghanistan and a pharmaceutical factory in Sudan. Clarke reportedly steamrolled intelligence officials who doubted (correctly) the evidence linking the Sudanese factory to either bin Laden or chemical weapons.

Those strikes, we now know, were primarily dictated by political rather than military concerns. They were coordinated because the United States wanted to prove we could hit two far-flung targets simultaneously (the attacks were dubbed “Operation Infinite Reach”) and perhaps even because some U.S. officials believed (erroneously) that the Sudanese had attempted to assassinate Tony Lake. And the search for a proper target in Sudan got further bogged down in an attempt to limit civilian casualties. The White House made a fateful decision to strike at night when no workers would be present. The result, as a little-noticed report by CNN recently explained, was that both attacks were delayed just long enough so that bin Laden left his Afghan camp an hour or two before the missiles landed. An uncharitable assessment might suggest that, for the second time in two years, Clarke was central to a decision that led to bin Laden’s escape.

BUT EVEN AS these decisions were backfiring, Clarke was demonstrating his real skill: political survival. He is the longest-serving member of the NSC. Universally described as a master of bureaucracy, he made himself indispensable to the NSC transition teams of both the Clintonites and the Bushies. He thus became the only NSC staffer from the first Bush administration retained by Clinton, and one of the only Clinton staffers kept on by the younger Bush. “Dick Clarke is the ultimate survivor,” says Larry Johnson, a former CIA officer and counterterrorism official at the State Department. “He is a bureaucrat’s bureaucrat. He knows how to write memos, move the paper. The guy’s a master.”

And it’s in political fights that Clarke has had his greatest triumphs. He worked the budget process to increase counterterrorism spending from $5.7 billion in 1995 to $12 billion in 2001. He helped lead a successful administration campaign to oust Boutros Boutros-Ghali as secretary general of the United Nations in 1996. More broadly Clarke tried, at the end of Clinton’s term, to formulate a new U.S. terrorist doctrine not dissimilar to the one now articulated by Bush—that the United States would not distinguish between terrorists and the states that harbor them. “We may not just go in and strike against a terrorist facility; we may choose to retaliate against the facilities of the host country, if that host country is a knowing, cooperative sanctuary,” he told the Associated Press in 1999. But nobody remembers this because Clarke didn’t have the stature to put counterterrorism policy on the front page.

His successor, needless to say, won’t have that problem. For William Downing there is nothing metaphorical about the “war” on terrorism. Downing is a highly decorated soldier who graduated from West Point and served several combat tours in Vietnam. He directed special forces in Operation Just Cause, which snatched Manuel Noriega from Panama in 1989. He also led them during the Gulf war. During Somalia, while Clarke coordinated policy from the White House, Downing commanded the elite U.S. troops on the ground. The 18 Americans killed in the October 1993 raid to capture warlord Mohamed Farah Aideed were directed by Downing, whose request to use AC-130 gunships for support was turned down by then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell—a debate that could be a harbinger of things to come in the current administration.

Since his retirement in 1996 Downing has been known mostly for his unvarnished views about how to fight terrorism. In a frank report on the Khobar Towers bombing, requested by the Pentagon, he blamed the general in charge of the facility for failing to take proper security measures. The general resigned. In the same report he called terrorism “a form of warfare,” and he explicitly rejected the idea of pursuing terrorists as we pursue criminals: “These terrorists are not criminals in the conventional sense. They must be seen as `soldiers.’” Downing noted as far back as 1996 what September 11 has made a cliche: You can’t fight terrorism without much better human intelligence. He also sat on the 1999 National Commission on Terrorism, which recommended many of the anti-terrorism measures now being rushed through Congress (see “Sin of Commission,” by Franklin Foer, October 8).

With respect to the ongoing debate within the administration about whether to target Iraq after operations end in Afghanistan, there’s no question about Downing’s views: He literally wrote the battle plan for overthrowing Saddam. Besides Paul Wolfowitz, the deputy defense secretary, and Richard Perle, a formal Pentagon policy adviser, few in Washington are identified as closely with replacing the current Iraqi regime. For the last few years Downing has advised the anti-Saddam Iraqi National Congress. His overthrow plan--unveiled to think tank conservatives and members of Congress—called for U.S.-armed and -trained rebels to launch an attack from safe zones within Iraq that are protected by American air power.

Clearly Downing possesses the right qualities for fighting a war on terrorism. The big question will be how well the four-star general maneuvers the internecine politics of the federal bureaucracy. Perhaps he should stop by Clarke’s office for some tips.

This article originally appeared in the November 5, 2001 issue of the magazine.