Ross Perot lives on Strait Lane in a world of his own. On the most exclusive street of millionaires in North Dallas, he has surrounded himself with alarms and sensors, fences and security guards. He has frequently deployed private investigators to uncover personally discrediting material about competitors. Those determined to humiliate and destroy him, he has explained, publicly and privately, include terrorists, drug lords, the CIA, and a criminal cabal of high officials in the Reagan and Bush administrations in which the president of the United States is complicit. Perot has convinced himself that the immense conspiracies arrayed against him will resort to any means necessary to achieve their ends. So he speaks frequently about assassination plots, and claims to have rewritten his will with martyrdom in mind.

The methods he uses to keep a hostile world at bay have even been exercised on his family. According to a reliable eyewitness, he has had his children followed systematically by a small brigade of private investigators, off-duty policemen, and company employees. Their friends have been subjected to secret investigations. The imperious father has forced his children to cut off close relationships, personally threatening to “ruin the lives” of certain friends he didn’t like. (Perot has refused to return calls about these episodes.) He fears his children may be taken hostage by terrorists, or held hostage by the terrors of a world he doesn’t control. Perot has brought the war home.

No one really knows when hostages first seized the high ground in his imagination. Perot has always claimed that he was recruited by the Nixon administration to pursue the POW issue in Vietnam. But a former State Department official, who coped with the consequences of Perot’s abortive flight to deliver Christmas presents to POWs in 1969, told me that the venture was Perot’s idea and never officially sanctioned. “He did it on his own. He volunteered,” former Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird remarked to the Associated Press recently about Perot’s involvement with the POW issue. In time the Nixon White House came to regard Perot as an eccentric nuisance, a problem child to be handled and isolated. Perot, however, persisted in inserting himself into the center of the POW issue and raising displays of hostage imagery. In 1970 he paid for and got Congress to exhibit inside the Capitol a Madame Tussaud-like diorama of two POWs in a bamboo cage, complete with cockroaches and a rat. When the POWs returned in the summer of 1973 to great fanfare, Nixon toasted them at a black-tie affair held in a tent pitched on the White House lawn. Not to be outdone, Perot staged his own welcoming ceremony at the Cotton Bowl, flying the POWs and their families to Dallas to witness a patriotic extravaganza. At the climax of the event, the klieg lights focused on the bleachers, and the host rose to accept the acclaim: Citizen Perot.

After that catharsis, the hostage issue seemed to fade, not only in the public’s mind but in Perot’s as well. “There just isn’t any reason for him to believe there are any more people alive back in there,” a Perot spokesman, William E. Wright II, declared in 1981. But the case that appeared to be closed by Perot was suddenly opened again. Over the Fourth of July weekend in 1980, Perot had paid for an encampment of 600 former Green Berets in Fayetteville, North Carolina, shooting off fireworks into the night and regaling the crowd with a long story about a physical confrontation between John Wayne and a “little sissy Swiss guy” whom he forced to cook him a steak. It was at this gathering that James “Bo” Gritz, an ex-Green Beret turned soldier of fortune, met with Perot to discuss an expedition into the jungles of Southeast Asia to rescue POWs. Perot put up the money.

In 1980, when Perot got himself named to head the governor’s task force on drug abuse in Texas, he demanded that the state build a heliport in his backyard so that he could make a fast getaway from terrorists and drug lords, who might kidnap or assassinate him. But wealthy neighbors objected. They suspected, the Dallas Morning News reported, that Perot wanted the heliport in order to make it easier for him to travel to his company’s headquarters if it were moved nearby. Though the heliport was never built, Perot’s firm did move three months later. He was peeved about the unfavorable publicity, afraid that it might provoke attacks. “You see,” Perot said, “that just excites the nuts.”

Down in the Caribbean, meanwhile, Perot was staging his own ersatz war on drugs, hiring an ex-Green Beret, Richard Meadows, who scooted around in speedboats but interdicted nothing. Perot presented the U.S. Customs Service with a scheme by which he would purchase a Caribbean island as a base against drug traffickers in exchange for which the government would grant him a monopoly on the services they needed, such as fuel. “If I’m going to buy a damn island down there,” he told a customs official. “I want my money back.”

In Washington Perot engaged in a nasty war with the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. When a group of veterans who wanted to construct a memorial had gone to him in 1979, he gave them some seed money. But he hated the design their selection committee chose: a black reflective wall on which would be chiseled the names of the fallen. “I’ll wipe you out,” Perot told John Wheeler, the leader of the veterans’ fund. He claimed that he would take a national poll that would prove his view. And he hired Roy Cohn, who had been Senator Joseph McCarthy’s counsel. Cohn demanded that the government audit the veterans’ accounts, and private investigations were launched into their personal backgrounds. Elliot Richardson, the former attorney general, served as the veterans’ lawyer. (Perot had resisted Richardson’s efforts as secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to audit his computer contracts, which were later found to involve exorbitant profiteering.) Richardson helped the veterans weather an audit by the General Accounting Office, which discovered no irregularities, and finally saw the building of the Vietnam Memorial. “If there’s anyone on the national scene dishing out crap in wholesale quantities,” says Richardson, “it is Perot himself.”

During the controversy over the wall, Perot lobbied members of the Reagan administration, including Reagan, to take his side, but he won no support. Many of those who had dealt with him back in the Nixon days had formed a strong negative impression. When Perot attempted to get himself appointed to the Defense Advisory Committee, and even got on a short list, Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger immediately struck him off. (Weinberger, another former HEW secretary, had objected to Perot’s rip-off government contracts under Nixon.) “He had a problem with Mr. Perot’s character,” a Pentagon official explained to me.

Just as it appeared that Perot would be shunted into obscurity, the hostage issue suddenly surfaced again. Six previous government investigations had concluded that there was no evidence of live prisoners. But the Reagan administration announced that it would attempt to resolve the POW-MIA issue at last. The effort, however, had an undesired political effect. The National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia, the principal group devoted to the question, which was granted quasi-official status, was assailed as a betrayer by a new, volatile faction. This motley collection of right-wing fund-raisers, soldiers of fortune, and mountebanks was dubbed “the Rambo set” by the administration officials in charge of the issue. On the border of Thailand and Laos, dozens of “forays” by middle-aged adventurers in fatigues were claimed. But the only live prisoner they captured was Ross Perot.

The billionaire became enthralled with the intrigues of the Rambo set. Finally getting himself appointed to a presidential post, the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, he began to “agitate” about their plots and sightings of MIAs, according to a Reagan administration official. “This crowd funneled things into Perot,” he told me. The split between Perot and the National League, which had generally approved his efforts under Nixon, was irrevocable. They were concerned with the return of remains, but Perot derided them as mere “bones.” He wanted the heroism of rescuing hostages.

In 1984 Bobby Garwood, an American soldier who had defected in Vietnam but had been returned, filed his court-martial appeal to the Supreme Court. He now claimed that he had seen live prisoners, though no evidence was ever produced. “That got Perot’s interest,” remarked a Reagan official. And Perot hunted after his fantasy quarry relentlessly. In 1985 the Detroit Free Press reported that Perot had financed twenty secret “forays” to free POWs—none of which yielded anything.

The Rambo set provided a crude but fantastical ideology that Perot readily accepted to explain why no MIAs were forthcoming: government conspiracy. Thus there was a reason for the frustration, and an even larger moral purpose to be served. The accumulation of highly specific but always evanescent detail on live prisoners was now matched by a pile of “facts” proving the conspiracy. Not only must the prisoners be found; the official corruption that prevented their discovery must be rooted out. The American people, no less than the MIAs, are hostages.

In 1985 Perot got entangled in a bizarre fracas that revealed his dependence on the Rambo set and impelled him to try to recruit Vice President Bush. Two former Green Berets, Major Mark Smith (also known as “Zippo” for having ordered a napalm attack on his own position) and Sergeant Melvin McIntire, claimed to have found startling new evidence about MIAs. A Pentagon investigation determined their information to be “either hearsay information from sources that could not substantiate the sightings, information that simply did not relate to Americans missing or unaccounted for in Southeast Asia, or information about an Army officer who died in captivity in 1961.” Smith and McIntire angrily responded by filing a lawsuit against President Reagan charging him with failing to act to liberate the POWs.

The two men traveled to Beirut and Singapore for surreptitious meetings with Robin Gregson, a mysterious British businessman who claimed to have a 240-minute videotape depicting thirty-nine POWs in a chain gang, yoked together, iron collar to collar, digging gold from a mine. But the video had a price. Perot, in constant contact, was eager to pay it. For this market of one, Gregson appraised the tape at $4.2 million. Perot wanted only to know where to send the money. He even went to Vice President Bush to tell him all about the coming breakthrough. Unfortunately, Gregson was jailed in Singapore for fraud. The credulous Perot put up $100,000 bail and offered $45,000 to a witness Gregson had fleeced as an incentive not to testify. Then, just when Gregson was supposed to close the deal, he declared that he had burned the tape, accusing the U.S. government of betrayal of the POWs. Perot stepped forward to explain that Bush had commissioned him from the start: “I was asked by our government to pursue this thing, to get the tape if it existed, and I said fine, it’s a long shot, but I’ll be glad to do it.” “I’m sure,” immediately replied Marlin Fitzwater, Bush’s spokesman, “he [Bush] didn’t ask him to make payments.” But Perot continued to insist that the tape existed: “The fact that we have one American, a Special Forces major, who says he has seen the tape, makes it more than just some bogus thing floating out there in Asia.” Perot’s willing suspension of disbelief reflected his demand to play a central role in the drama.

Undeterred by the Gregson debacle, Perot pressed on. Having secured the presumed movie rights, but then having lost the movie, Perot tried to pre-empt the Reagan administration and Congress as the leading man. His chief promoter for the role was Representative Bill Hendon, a Republican from North Carolina, who had participated in the meetings with Gregson. Hendon had become obsessed with the notion that the government was covering up its own conspiracy not to find the prisoners. He delivered eighty files to a House task force, which reported in 1984 that “there is no government cover-up of information on live prisoners.” A year later the House Select Committee on Intelligence reaffirmed the conclusion. But Hendon continued to harp on conspiracies and raise money for various ephemeral front groups of the Rambo set. One of them, the so-called POW Policy Center, sent out an appeal for contributions to a fund that would offer $1 million in gold for each POW. The letter read: “We plan to purchase 10,000 copies—in the Vietnamese language—of hit movies like Rocky, Indiana Jones, and Kung Fu, and intersperse our reward offer into the videotapes.”

Hendon formally proposed that Congress authorize a “Perot Commission.” The resolution included a poll finding: “73 percent of the American people believe the North Vietnamese are still holding American prisoners of war.” Perot demanded that his commission be invested with the power of arrest.

In 1986 General Eugene Tighe, former director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, delivered his report on POWs to Congress. He dismissed charges of cover-up. On the question of whether there were prisoners still being held captive, he said: “No one knows the answer.” Thus the seventh investigation came no closer to providing evidence of live MIAs than the others. As a witness before the same committee that had just heard Tighe, Perot claimed to possess the names of sources who knew that the POWs were alive, but would neither produce them nor give any reason why he wouldn’t. “Certainly,” he testified, “the evidence is overwhelming that people are there.” He advanced himself as the one to find them. But the committee voted down the Perot Commission—a notion opposed by the National League, the administration, and almost all representatives, Democrats and Republicans alike.

Rebuked, Perot staged a guerrilla raid to recapture the issue by a sudden flight in March 1987 to Vietnam. “I still believe we left men behind,” he announced, claiming that his trip was taken at the request of the president. Shortly after his landing back home, though, the White House released a terse statement: “The government was not aware that Mr. Perot had gone to Vietnam until after he had returned.” The National League also made a statement: “Mr. Perot has not contacted the League to provide the families of the missing men with any information.” But Perot insisted to the White House staff that he present his findings to Reagan. He was ushered into the Oval Office, where he proclaimed, according to an administration official, that about 300 POWs were alive in Laos, and was promptly ushered out.

Perot, out of the play, turned to Bush. Perhaps, he suggested, he should offer to buy Cam Ranh Bay as a form of ransom. “It’s just an idea,” said Perot. Bush rejected it, and Perot raised the ante, taking up the popular notion of the Rambo set of offering $1 million per live prisoner. And he demanded to study intelligence files in order to prove his theory of government conspiracy and cover-up. Bush granted him access. The files showed nothing. And Perot continued to rail about conspiracy. Bush cut him off. Reagan cut him off. Weinberger cut him off. Frank Carlucci, the national security adviser and then Weinberger’s successor at Defense, cut him off. General Colin Powell, Carlucci’s successor at the National Security Council, cut him off. The bitterness against Perot was uniform and intense. One of his responses was to renege on his $2.5 million pledge to the Reagan Library. Another was to redraw his will. “If I’m killed,” he speculated, “my will is written so that the bulk of the estate goes into the fight, the fight to get back our men, and the fight to expose what was done to keep them in Communist jails. So my death won’t benefit anyone.”

Perot retreated deeper into the thicket of conspiracy theories. He absorbed much that was elaborated by Daniel Sheehan, the leader of the radical left-wing Christic Institute, about a vast conspiracy at the center of which was a drug-running, assassinating desperado. Who was that desperado? None other than Richard Armitage, the assistant secretary of defense in charge of the POW-MIA issue. Perot also began to imbibe the concoctions of Scott Barnes, the author of a thick tract filled with highly detailed plots titled “Bohica,” a codename for a secret military expedition. Barnes claimed to be an ex-Green Beret and intelligence agent, who swam the river between Thailand and Cambodia, photographed a live prisoner, then discovered POWs in Laos and was ordered by the CIA to kill them. In fact, Barnes spent most of his time in the Army held in detention before being discharged; there is no river between Thailand and Cambodia; and he produced no proof about the CIA assassination plot. The NSC issued two official statements on his “fabrications.” And Colonel Joseph Schlatter, the chief of the special office for POWs and MIAs at the Defense Intelligence Agency, in a letter to the National League, described Barnes’s assertions as “nothing more than a collection of his fantasies.”

Barnes linked his tales about Armitage to two business failures, lending the conspiracy an aura of factuality: the Australian-based Nugan Hand Bank, which did have ties to drug lords and did have former U.S. intelligence operatives in its hire; and the Hawaii-based Bishop, Baldwin company, whose chairman, Ronald Rewald, vainly defended himself against charges of massive fraud by claiming that his firm was really a CIA front. Barnes added that he had been approached by the CIA to assassinate Rewald so that he wouldn’t talk. At the center of the octopus, Barnes insisted, was none other than Armitage, manipulating these far-flung enterprises for his drug deals.

Perot demanded that the Senate take Barnes’s testimony, which it did and then filed it on a dusty shelf. The CIA, for its part, investigated his charges about Nugan Hand, concluding that there was no larger conspiracy. Admiral Bobby Ray Inman, the CIA’s former deputy director, who conducted the study, met privately with Perot to try to allay his suspicions. “I knew they would keep you in the dark,” Perot told him, according to U.S. News & World Report. “Barnes is credible and knows what he is talking about,” Perot informed the Prescott, Arizona, Courier, a newspaper near where Barnes lives that has reported on him. Perot acknowledged that he has spoken with Barnes “numerous times,” and he asserted that Barnes “has been harassed and treated miserably by the U.S. government.”

“Perot had a tremendous amount of evidence already,” Barnes told me about the conspiracy and cover-up. “Once he gets in the White House, he’ll start to clean out. He’ll get tough on this top brass involved in dope dealing. Generals, admirals, assistant secretaries of defense, they don’t want him in.... They better look out. Colin Powell would be history. It goes directly to Bush. We know that.... He did nothing to get the POWs home. There’s a cover-up. The evidence is overwhelming.” (Barnes, by the way, says he still talks regularly with Perot. The last time, he says, was about three weeks ago.)

At roughly the same time that Perot was being thwarted in his bid to take command of the POW issue, he was also being frustrated at General Motors. The mythology of Perot vs. GM is that of the innovative individual who attempts to reform the unresponsive bureaucracy. But the Los Angeles Times, in a story on June 15, punctures this popular tale. Perot’s efforts to maximize profits for his merged company and for his executives, at the expense of GM, were halted amid much rancor. His response was to plot secretly to “nuke” the corporation “by shutting down its computer systems and thereby paralyzing its auto production,” according to the Times’s report. Perot’s own executives rebelled against his destructive ploy. Finally, GM bought him out. The pattern of his behavior in both the GM and POW affairs is remarkably similar: when he fails to get his way, he turns vindictive, looking for someone to destroy.

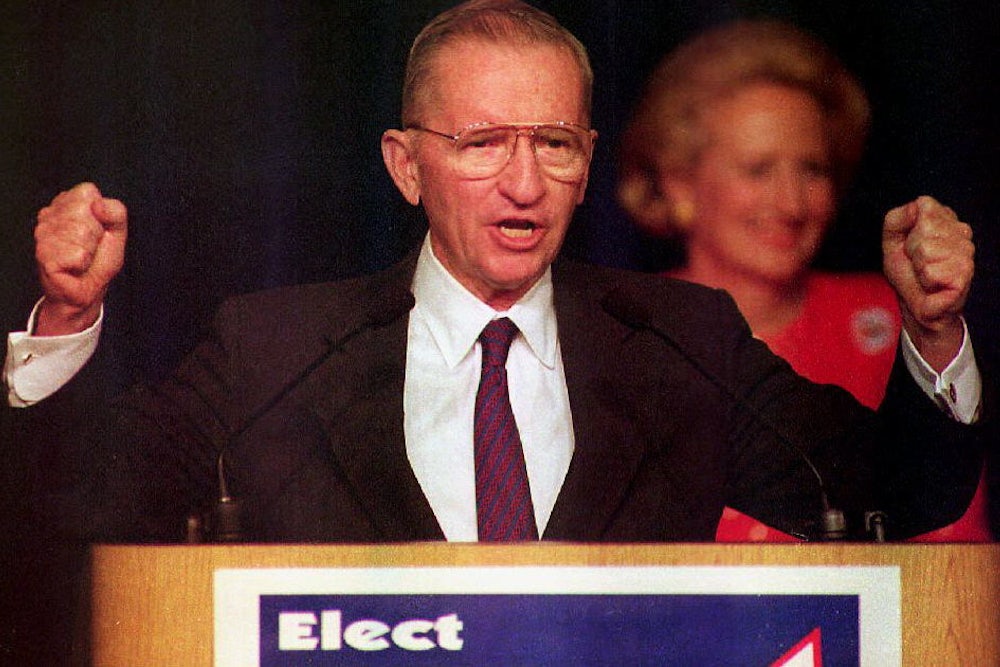

After his GM debacle, the themes all came together at a huge dinner he staged at a Dallas hotel in 1987. Ostensibly, the gala was a homecoming, to welcome the hero from his “foray” in Detroit. A hotel clerk dressed in a POW’s fatigues was literally chained to the hors d’oeuvre table. “The house lights dim,” reported David Remnick in The Washington Post. “Perot walks down the center aisle flanked by two uniformed combat soldiers.... The soldiers escort him to a makeshift throne on the stage.... The set decorations are a dark dungeon cell and an angry-looking banner behind him written in Arabic.... At one table a woman can no longer contain herself. `Run Ross! Run for president!’ she shouts.... The band pumps out ‘Hail to the Chief,’ a gigantic American flag unfurls above the stage, and Perot rises from his throne.”

In 1989 the battle against the conspiracy entered a new phase when Armitage was nominated to be secretary of the Army. Two years earlier Perot had told the Associated Press: “I have never said a word to anybody about drugs and weapons and Armitage.” Now he mobilized against him. Perot lobbied members of the Senate, generals in the Pentagon, and members of the press, showing them a picture of a nude Vietnamese woman with whom he implied Armitage had an affair. (David Rogers and Jill Abramson reported in The Wall Street Journal on June 12 that Perot had hired a private investigator to seek out damaging material on Armitage.) When the charges against him were first raised, Armitage, fearing he was embarrassing the government, offered his resignation to Weinberger, who refused it. “You’ve done nothing wrong,” he told him, according to a Pentagon source. Armitage then met with Perot, who demanded he quit. “You’ve compromised yourself,” Perot insisted.

After Armitage’s nomination, Perot went to the FBI, elaborating his stories about Armitage. “We went to extraordinary lengths to check out the allegations,” Buck Revell, the FBI agent in charge of bureau investigations in Washington and now the FBI chief in Dallas, told me. “There was a great deal of smoke. I didn’t want there to be any questions. We got to the bottom of everything we could get to the bottom of. We found nothing about drug smuggling and cover-up on MIAs.” Revell presented his findings to Perot. “As long as it’s been checked out that’s fine with me,” Revell says Perot told him. But Perot continued to spread the rumors about Armitage and to show the picture of the naked woman. Partly because of the pressure that Perot applied, Armitage declined the nomination, though nothing had been proved against him.

While Perot was waging his little war against Armitage, his representative, Harry McKillop, was shuttling back and forth to Vietnam, thirteen times, presumably in search of MIAs. But Patrick Tyler reported this month in The New York Times that there was another agenda: Perot was wringing a monopoly commercial concession from Vietnam in 1990 in the event that relations were ever normalized. Business Week followed with a report that McKillop told a ranking member of the Vietnamese Foreign Ministry: “We are satisfied with the MIA issues and can put that behind us. The time is ripe for American companies and [Perot] himself to invest in Vietnam. We should be concentrating on business and economic relations.” Was Perot’s crusade a mask for his finagling? “This is not true,” Perot replied when the Times story was published. And he suggested, according to Tyler, “that Vietnam’s politburo had made a determination that it could curry favor with the Bush administration ... by sabotaging Mr. Perot’s putative run for the White House.”

Perot now talks openly about assassination plots against him. “It’s a deep concern of his,” Barnes told me. “He’s going to be the next president if he’s not assassinated.” In an interview with C-SPAN this year, Perot claimed that he was on a North Vietnamese hit list: “They used to come to Canada and give a list of people to kill, and I was on that list.” The FBI, he went on, “had infiltrated the group, knew ... whose life was threatened.” It was “all public record.” But an FBI spokesman said the bureau had “never heard of” the plot. Then Perot told The New York Times that unnamed sources in the CIA informed him that he “might quietly disappear” for pursuing the MIAs. The Viet Cong, he charged, had also asked the Black Panthers to murder him. Perot’s logic was this: he alone could make a deal to free the prisoners, and even forge a business arrangement, with those who were his purported assassins, who were at the same time trying to destroy him to win concessions from George Bush. Or something along those lines.

With each new story, Perot’s denials have mounted. “Never once” had he financed a “foray” for MIAs, he told Newsday. All the memos about his offers of assistance to the Nixon administration, excavated in the National Archives, “were fabricated to help Republicans politically,” he told C-Span. All his efforts on behalf of POWs were taken at the behest of presidents: “I did not ask to do it. I did not want to do it.” But Perot was going to get his chance to explain everything publicly on June 30 at a Senate committee hearing on the whole history of the POW-MIA issue, chaired by Senator John Kerry, a decorated Vietnam veteran. Boris Yeltsin, the Russian president, responding to the committee’s inquiry, even revealed that live prisoners captured during the Vietnam War were moved to Soviet labor camps and that some might still be alive. It was the first real breakthrough. If any definitive answer could be given to the question of MIAs, Yeltsin might give it. But this makes him, not Perot, the rescuer.

Perot was carefully courted to testify by Kerry, who spent hours with him. Perot was still obsessed with conspiracies and cover-ups. In March, when committee staffers met with him in his Dallas office, he rambled on about Armitage and flourished the picture of the nude Vietnamese woman, which he keeps in a safe. He insisted, according to a committee source, that Rewald had been unjustly imprisoned. A day before he hired Ed Rollins and Hamilton Jordan as his handlers, he agreed to appear. Perot demanded and received classified clearance to review secret documents. (In May he told Newsweek editors in an off-the-record session that there were about thirty live prisoners in Laos. “The number he gives depends on the time of day,” said a committee source.) But on June 15 he sent Kerry a letter declining to appear, charging in advance that the hearing would be a “political circus.” So he rejected the one opportunity he had to testify under oath on the question he had defined as paramount: “I have one mission in life,” he claimed in 1987, “and that’s to get to the bottom of the POW-MIA situation.” Suddenly, it seemed, it was not the MIAs but Perot’s search for the MIAs that mattered.

Perot’s balking at the Senate Committee should surprise no one. (“If I were Ed Rollins,” said a committee source, “I’d probably do the same.”) Perot’s obsessive mentality has its own momentum, which must never be derailed, least of all by the slow, cold sifting of empirical fact. Perot must always expose new layers of conspiracy and always reach for higher authority to strike it down. Whenever his claims are unproven or disproved, he simply leaps ahead. He must maintain his relentless progress, or face the collapse of his elaborate fantasies and be exposed himself. He trusts no one with independent power to tell him the truth—not the FBI, the CIA, the Senate, the Pentagon, or the White House. Only he himself can absolutely confirm his own reality. And the only way Ross Perot can ultimately do that is to become president of the United States.

This article originally ran in the July 6, 1992 issue of the magazine.