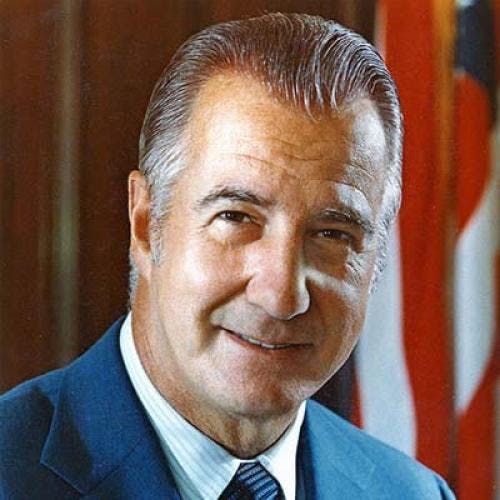

There Agnew was on television, speaking with mawkish self-pity of his "nightmare-come-true" and at the end saying "thank you, good night and farewell" in a sepulchral tone that made some viewers wonder whether he was saying farewell to life. The remarkable thing was that it was so easy, so soon after Spiro T. Agnew resigned and asked a federal judge to find and declare him a felon in order to escape indictment and probable conviction for many more and larger felonies, to adjust with amazement, satisfaction or regret to the fact that this man was no longer the Vice President and potentially the next President of the United States. It was almost as if he had never been what he became in 1969 and remained until he was found out and brought down in 1973; the embodiment in the minds and hopes of millions of Americans of the rectitude, the order, the simple dedication to simple rightness that they missed in their society and were led by Agnew to believe they had been done out of by elitist snobs and grubby malcontents.

The President who had plucked Agnew from the sewer of Maryland politics and conferred him upon the nation behaved and had his spokesmen talk as if he wanted his sometime Vice President to be forgotten and banished from the public mind as soon as possible. Agnew in his televised farewell spoke of "a great President." He thanked Mr. Nixon for "his attempt to be both fair to me and faithful to his oath of office" and for "the restraint and the compassion which he has demonstrated." He also let a friendly interviewer, Frank Zan der Linden of the Nashville Banner, portray him as a broken and embittered victim who felt that he had been unfairly driven from office. The contradiction was more apparent than real. Agnew must have known since early August, when the first news of his involvement in a federal investigation of Maryland corruption was published, that the President wanted him out of office and out of the Nixon administration. But it's believably said at the White House that the President got him out without ordering him to quit or confronting him with an explicit ultimatum.

One of Mr. Nixon's staff counsellors, former Congressman and Defense Secretary Melvin Laird, admits now that he began warning congressional Republicans in early August that the evidence against Agnew was serious and substantial. Counsellor Bryce Harlow, one of Agnew's few friends in the Nixon inner circle, and J. Fred Buzhardt, a White House lawyer, were assigned by the President in mid-September to convince Senator Barry Goldwater that any public defense of Agnew would be futile and foolish. They were ordered to summarize for Goldwater the accumulated evidence that Agnew had solicited and taken money from Maryland contractors before and after he became Vice President. Senator Hugh Scott, the Republican floor leader, indicated to other Republican senators on the implied authority of the President that they could soon be sitting in judgment of an impeached Vice President and that they therefore had better be cautious in discussing the matter. While Agnew was being deprived of congressional support in this fashion, not necessarily in a vindictive effort to destroy him but certainly to minimize foreseen embarrassment to the administration and the Republican Party, Fred Buzhardt was arranging and managing negotiations between Agnew's lawyers and Justice Department prosecutors for a bargained plea. This maneuver almost succeeded in September and finally did in October, when Agnew realized that the evidence against him and the web woven around him were more than he could overcome or escape. His cry in a speech on September 29 that "if indicted I will not resign" was not the promise of indefinite defiance that it was understood to be at the time. Agnew had known for weeks that the President wanted his resignation. His assertion on the 29th was his way of saying to Mr. Nixon and to Attorney General Elliot Richardson, who said later that the President approved every major step in the plea negotiations, that the President could have the desired resignation only if the Vice President were let off without indictment, trial and predictable imprisonment. That's the way it ended — with a $10,000 fine, probation for three years, and a pledge of no further federal prosecution in return for the resignation and Agnew's assent to the publication of utterly damning evidence that he'd been taking money from Maryland contractors for 10 years and was still doing it in December of 1972.

The President's choice of a successor to Agnew is of such numbing ordinariness that I've nothing to say about its merits except that it should have been better and could have been worse. Congressman Gerald Ford of Michigan has been reciting the virtues of Richard Nixon and of his legislative proposals once a week in the White House press room since 1969 and I've yet to hear him say anything that was memorably bright, critical of the President, or indicative of profound understanding of anything. I was impressed in 1969 with Representative Ford's cool and intelligent estimate, provided in a private interview, of the abilities and attitudes then prevailing at the Nixon White House, and repelled by his savage and shoddy attempt to bring about the impeachment of Associate Justice William O. Douglas. What I find interesting at the moment is the way in which the President went about or anyhow professed to go about the choice. A key fact to be kept in mind is that Mr. Nixon must have anticipated since late July or early August that he'd have to nominate a successor Vice President who would be confirmed by majority vote in the House and Senate without a damaging fight. Was the President's elaborate show of canvassing many possibilities, reducing a long list of possibilities to five and two and finally to Ford, for real or was it a charade? "All I can tell you," one of the senior participants in the exercise said while it was going on, "is that he's acting as if it's for real." Melvin Laird said after the choice was announced that he asked Ford several weeks ago whether he'd want the nomination. This indicates but hardly proves that it was a charade. One of the few established facts is that the President didn't ask Laird, Bryce Harlow or his third counsellor, Anne Armstrong of Texas, to tell him whom they preferred and tell him why they did. So far as is known Mr. Nixon didn't invite or tolerate in-person or face-to-face discussion and argument with anybody, on his staff or in Congress or among the party leaders. He instructed his staff chief, General Alexander Haig, to instruct other senior assistants to put down three choices, in order of preference, and to submit the lists to him through Haig — unsigned. It seems to be true, though one of the President's wisest and closest advisers finds it hard to believe, that he never personally discussed the choice with John B. Connally, who completed his tum from Democrat to Nixocrat to Republican early this year and has Mr. Nixon's promise of support for the Republican presidential nomination in 1976. Haig discussed the Agnew succession with Connally twice, by telephone, with the end result that Mr. Nixon and Connally communicated their agreement with each other to each other through Haig that it would be better to save Big John for 1976 and duck the bruising struggle in Congress that would have resulted if he'd been proposed for Vice President. Connally indicated to at least one unofficial friend in Washington that he hoped the President would pick Governor Nelson Rockefeller, who is likely to be a principal contender for the presidential nomination in 1976. Connally figured that three years as Mr. Nixon's second Vice President would probably finish off Rockefeller or anybody else as a serious 1976 contender. Rockefeller was foolish enough to want the vice presidency and he figured in one of the four announcement drafts that the President had his speech writers prepare.

Mr. Nixon indicated to Ford but didn't quite tell him on the morning of October 12 that he was the choice. Ford was also told that he might be getting a telephone call from Haig. At about 7:30 pm the President telephoned Ford and told him that Haig had something to tell him, which Haig did after calling back on another line with an extension so that Mrs. Ford could share the moment with her husband. She was told to stay out of sight at the White House and out of the White House East Room, where the choice was announced at 9 pm, so that her presence wouldn't tip off the assembled dignitaries and the media. The President had his surprise and his fun, with a televised display of pomp and power that seemed to me to be singularly vulgar and inappropriate. Spiro Agnew and the occasion for the nomination of Gerald Ford were not mentioned.

This article originally ran in the October 27, 1973 issue of the magazine.