Boston—In his bid for re-election, Senator Edward Kennedy is suffering. Among many younger voters, the memory of Mary Jo Kopechne and William Kennedy Smith outweighs that of John F. Kennedy. Boston talk radio abounds with abuse against what one host described as the “the bloated bulbous nose boob from Beantown.” Perhaps more important, for the first time ever, more Massachusetts voters now identify themselves as independents than as Democrats—41 to 45 percent. The state's politics are no longer symbolized by the Kennedys and former House Speaker Tip O'Neill, but by Republican Governor Bill Weld and former Democratic Senator Paul Tsongas. “There is a big bloc of voters, as high as 40 percent of the electorate, that is no longer available to Kennedy,” a Boston pol who is advising the senator's campaign confided. “If anyone runs a minimal campaign, he'll get at least that much of the vote.”

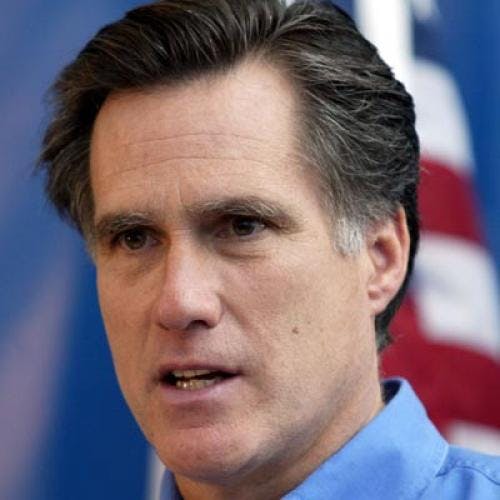

Sadly for Kennedy, his challenger is more than a minimal candidate. In fact, Mitt Romney, the son of former Michigan Governor George Romney, has all the attributes of a genuine Kennedy-threat: he's youthful, handsome and very articulate; he's also a moderate who can appeal to the independents who now hold the balance of power in the state's elections. He's built his campaign on his career in business. “Mitt Romney has spent his life building more than twenty businesses and helping to create more than 10,000 jobs,” an ad says. “So when it comes to creating jobs, he's not just talk. He's done it.”

The Kennedy campaign has tried to portray Romney, a Mormon born in Michigan, as a cultural outsider. And while Romney can't count former Boston Mayor John Fitzgerald among his forbears, he does epitomize the new Massachusetts of computer programmers and management consultants. After graduating first in his class at Brigham Young University in 1971, Romney and his wife, Ann, moved to Boston, where he enrolled in a joint program at Harvard Business and Law Schools. In 1977, he joined a new consulting firm, Bain & Co., and seven years later, headed a spinoff, Bain Capital, which both advised and invested in firms—sometimes through leveraged buyouts financed by junk bonds. Romney was successful. In the past two years, he earned $13.6 million. But like other financial repo men, Romney also oversaw the elimination of jobs through downsizing and mergers.

Romney bought an estate in Belmont, a posh suburb of Boston, where he and Ann reared five sons. He became a leader in the Mormon Church, and in 1986 was appointed president of the church's “stake” in the Boston area. Between church and business, he had little time for politics. He was registered as an independent and in 1992 crossed into the Democratic primary to vote for Tsongas. Last year, however, he decided to seek the Republican nomination against Kennedy. Romney was drawn into politics by the example of Weld, who through his victory in 1990 redefined Massachusetts Republicanism.

In the '60s and '70s, Massachusetts Republicans were New Dealers distinguished from Democrats primarily by their ancestry. Then, in the early '80s, the party lurched to the right, nominating Reagan conservatives for the governorship and the Senate, all of whom were soundly defeated. In 1990, Weld, who had resigned from the Justice Department to protest Ed Meese's transgressions, introduced a new kind of Republican politics: supportive of abortion and gay rights, tough on crime, willing to use government to protect the environment and stimulate high tech business, but also eager to privatize government and cut the state payroll.

Romney has followed Weld's script. As a Mormon official, he shared the church's opposition to homosexuality and abortion, but as a candidate, he has moved steadily toward Weld's positions on both. He supports Roe v. Wade and the state's laws banning discrimination against gays. He also has followed Weld in making crime and welfare reform centerpieces of his campaign.

The question about Romney is where he would stand in Congress's internecine battles. Would he side with Republicans such as John Chafee who have tried to develop constructive alternatives to Democratic legislation or with Republicans such as Phil Gramm and Newt Gingrich who have been willing to paralyze Congress for the sake of embarrassing the Clinton administration? Romney has indicated that he would side with the moderate wing. He endorsed the crime bill and refused to back Gingrich's jejune “Contract with America.” He told me he would have backed Chafee's health care bill. “I'm willing to vote for things that I am not wild with,” he said.

Romney also seems to eschew ideological absolutes. He favors a balanced budget, but acknowledges that it could not occur until the twenty-first century. He favors getting welfare recipients to work, but does not favor eliminating welfare with the idea that a bracing chill of poverty would invigorate the poor. He backs a modest tax cut for the middle class, but rejects a reduction in capital gains because it would raise the deficit.

When I asked him about Clinton administration subsidies for high technology, he declared himself opposed. “I don't think it is possible or wise for government to predict where we can be the most competitive or where we can create the most jobs,” he said. But then he undermined his own position by adding that it would be different “if we found a competing government massively investing in a technology that would devastate one of our key industries.” That, of course, has been the rationale for all the existing subsidies, from the government-financed semiconductor project, Sematech, to flat panels.

Like other new candidates this year, Romney seems to have given little thought to foreign policy. In three days of speeches, I only heard him mention it once. When asked how he would preserve a local Air Force base, he cited its importance in developing an anti-missile defense against the eventuality that “someone like North Korea creates a nuclear weapon and combines it with a Chinese-made rocket and launches something of that nature toward one of our allies or toward us.” No one queried Romney if he knew the distance from Pyongyang to L.A.; the discussion moved on to campaign reform. The election doesn't hang on a grasp of foreign affairs.

Kennedy's difficulties often are compared to Mario Cuomo's in New York, but there are important differences. Cuomo's character is above reproach; it's his performance as governor that is hurting his chances of re-election. By contrast, Kennedy's record as a senator has been exemplary. It's largely because of him that Congress did anything about job training, student loans, child care, family leave, handicapped rights and aids. And Kennedy always has been far more amenable to compromise than his ringing populist rhetoric suggests. He worked with Dan Quayle in 1984 to develop a job training bill and took the lead last summer in trying to forge a last-minute health care deal with Republicans.

Some Democrats have supported him because of these skills, but many have been drawn to him by his mythic status. They are now defecting, forcing Kennedy to fight for their allegiance on other grounds. It hasn't been easy. Last month, as Romney pulled ahead in the polls, Kennedy responded with an unseemly attack against Romney's Mormonism. The jab backfired, as Romney and the Boston papers quoted back to Kennedy his brother's insistence in 1960 that he be judged for himself and not his religion.

After a debate within his campaign, Kennedy is now sticking to two messages. He is touting his ability to get things done for his constituents. The appeal resonates in Massachusetts: economy is still reeling from the loss of federal defense funds; Boston urgently needs money for a new harbor tunnel and the clean-up of its surrounding waters. But Kennedy does not appear comfortable emulating Dan Rostenkowski's re-election strategy. At a luncheon held by Salem's Rotary Club, Kennedy rambled and seemed only half-awake as he enumerated the millions he had brought to the seaport.

Kennedy also has started attacking Romney's record as a businessman—charging him with putting “profits over people.” For the first time, Kennedy is running negative commercials. One features workers from a plant in Marion, Indiana who were thrown out of work and then rehired at lower wages and benefits by a firm acting under Bain Capital's direction. The press also uncovered another company, Damon, that, with Bain's guidance, sold its Massachusetts operations to another firm, which promptly closed the facilities, costing the state 116 jobs. These stories have put Romney on the defensive, and he is now running ads that hint at Kennedy's age and girth.

Most of the local press and pols believe Kennedy will win. If he starts out with 40 percent of the electorate against him, he also starts out with more than that in his favor. Romney, however, could still pull it out. When the two debate on October 25 and 27, the challenger will try to reinforce the contrast between his vigor and Kennedy's senescence. Kennedy's campaign is aware of the danger. As one adviser explained to me, “The one thing Kennedy has to avoid is doing anything that makes him look like a dinosaur.” But it's one thing to be aware of danger and another to avoid it. As Kennedy stumbled over his lines in Salem, you couldn't help but feel that, no matter the outcome, this will be his last campaign.

John B. Judis is a senior editor at The New Republic. This article appeared in the November 7, 1994, issue of the magazine.