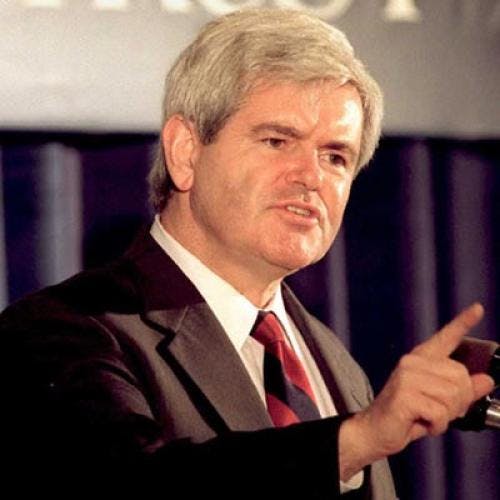

I've figured out what's so different about Washington in 1995. It's Newt. Pretty obvious, huh? And yet there's more to the Newtization of the political culture of Washington than meets the eye. Newt Gingrich is the most influential non-president since ... well, since as far back as I can remember. Lyndon Johnson was a powerful figure as Senate majority leader in the 1950s--before my time--but even he didn't drive the agenda or dominate the town like Gingrich does. (LBJ didn't teach a college course, either.) Gingrich has snuffed out the storyline in Washington that had endured since Franklin Roosevelt's era, namely the ups and downs of the president. Now the story in Washington is the agony and ecstasy of Gingrich. The media reflects the shift. Until the Republican triumph last November, almost all press coverage in Washington boiled down to one question: How's the president doing? Now the question is: How's Newt doing? President Clinton and congressional Democrats have been reduced to reacting to Gingrich. The White House's primary aim is to attack selected parts of the Contract with America, the ten-point House Republican agenda put together by Gingrich. House Democrats have a one-point Contract with America--nail Newt. He has also altered reading habits in Washington. Books on his reading list for GOP freshmen are suddenly popular, and publishers are eager to take advantage. One Gingrich favorite (and an important book in its own right), The Tragedy of American Compassion by Marvin Olasky, is featured in a paperback edition with a new blurb on the front cover, "Recommended by Newt Gingrich." One more thing. Roger Clinton, the president's half brother, has been crowded out by Gingrich's half sister, a lesbian named Candace Gingrich. Her reflected glow is hotter than his.

In Newt's Washington, the rules of media courtship have changed. For decades, politicians of all stripes sought the approval of The Washington Post, The New York Times, the national news magazines and the T.V. network news folks. They did so by granting access, dispensing leaks, issuing lunch invitations, etc. Even Ronald Reagan--or I should say, especially Ronald Reagan--courted the usual press sources. His staff treated The Washington Post as the arbiter of how they were doing. Bad coverage meant they were screwing up. Gingrich concludes exactly the opposite. Bad coverage in the mainstream media means he's doing well. He and his allies court a different wing of the media entirely. Gingrich's sidekick, Majority Leader Dick Armey, passed up lunch with the editors of Post to be interviewed by the editors of the more conservative Washington Times. Gingrich is sure to be more upset by a discouraging word on the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal than by a dig in Newsweek. And if talk radio happened to zing him, Gingrich would go bonkers. He has invited talk radio hosts to broadcast from the Capitol, and they've accepted. When they go on the air, he invariably drops by to chat. Most days, neither he nor his aides bother to watch the evening news shows.

Gingrich's ascendancy has produced an unintended consequence for the Republican presidential race. It's been diminished. Not by Gingrich's decision to stay out of the contest (for now, at any rate), but by the enthusiasm he has generated among Republicans for the GOP Congress. My sense is that Republicans are so excited about what Congress might do, they don't have time to get whipped up about the contest for the 1996 nomination. There's remarkably little passion for any of the presidential candidates now. This is especially true among conservatives, precisely the folks the candidates are wooing most avidly. To the extent conservatives have followed the presidential race, they like Phil Gramm, respect Bob Dole and are intrigued by Lamar Alexander, a moderate who has taken up conservative rhetoric. But the truth of the matter is that few conservatives, or other Republicans, are paying much attention. They probably won't before August, when Newt and Congress take a long recess and the fate of the Contract with America and the future of federal spending are known.

While the press continues to forecast a revolt by Republican moderates, quite the opposite has happened: Gingrich has corralled them. Depending on your definition, there are anywhere from two dozen to five dozen moderates in the House. Yet only two voted against the balanced budget amendment, and only two (a different two) rejected the regulatory moratorium. The yapped-about coalition of the center--moderate Republicans joining moderate Democrats--hasn't materialized. Gingrich hasn't allowed it. He lovebombs moderates with attention, inviting so many to strategy sessions that conservatives get ticked. But it works. When Gingrich is criticized on gay issues, for instance, Steve Gunderson of Wisconsin, the lone gay Republican in the House, rushes forward to defend him. Only once have moderates crossed Gingrich. Hours before a vote on reviving Star Wars, two dozen met privately and decided to vote no. They didn't inform Gingrich. Their votes were pivotal as funding for Stars Wars lost, and Gingrich was embarrassed. Still, one vote doesn't constitute a revolt. If there is a revolt, it's by moderate Democrats, who more often than not vote with Gingrich on big issues.

The ultimate reflection of Gingrich's power is the way he dominates the Washington mind. Yes, there is such a thing deep inside the Beltway. Gingrich has become the standard of measurement. Everyone is compared with him. Armey, it's agreed, lacks an ego as big as Gingrich's. Armey's office in the Capitol is austere. There are no power pictures--of Armey with, say, Margaret Thatcher or Charlton Heston--on the walls. Bob Dole? He doesn't measure up to Gingrich as a political visionary. He jokes that he'll let his pollsters discover a vision. Strategists? Are there any in Gingrich's league? The only ones mentioned are William Kristol and Representative Bill Paxon of New York, a Newt protégé. Lobbyists? The coin of their realm is closeness to Gingrich. The closest is former Representative Vin Weber of Minnesota, who was Newt's alter ego for a decade. Two of Weber's former staffers are now top Gingrich aides. What about the comparison with Clinton? It's been overworked, notably by me. Gingrich and Clinton are both guys with good memories and the gift of gab. But comparing their poll ratings, now routinely done in Washington, is dumb. National popularity is a significant ingredient in the president's ability to govern. But it hardly affects a House speaker, who faces voters only in his own district. Whipping Congress toward enactment of his agenda won't make Gingrich popular. It does make him king of the Washington mountain.