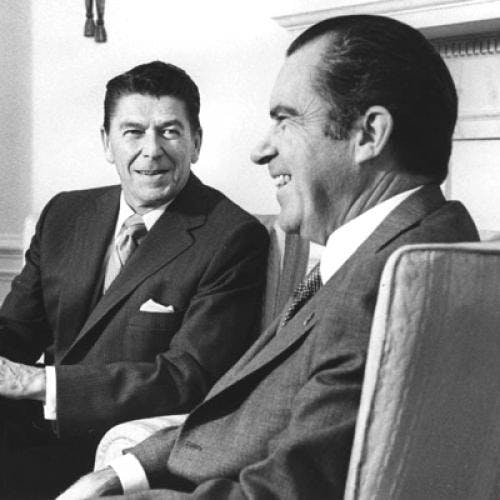

The imperial presidency in the United States has staged a comeback some 13 years after the fall of Richard Nixon. Both the recent renewal of presidential aggrandizement and the reaction against it recall the latter days, hectic and ominous, of the Nixon presidency, when I wrote The Imperial Presidency. My argument then, as now, was that the American Constitution intends a strong presidency within an equally strong system of accountability. My title referred to what happens when the constitutional balance between presidential power and presidential accountability is upset in favor of presidential power.

The perennial threat to the constitutional balance springs from foreign policy. Confronted by presidential initiatives at home, Congress and the courts—the countervailing branches of government under the separation of powers—have robust confidence in their own information and judgment. But confronted by presidential initiatives abroad, Congress and the courts, along with the press and the citizenry, generally lack confidence in their information and judgment. Consequently, in foreign policy the disposition has been to hand over power and responsibility to the president.

The presidency had always flourished in times of war. “We elect a king every four years,” Secretary of State William H. Seward told a London Times correspondent during the Civil War, “and give him absolute power within certain limits, which after all he can interpret for himself.” But in the past, peace has brought reaction against executive excess. Within a dozen years Seward’s elective kingship theory faded away, and the post-Civil War era was famously characterized by Professor Woodrow Wilson as one of “congressional government.”

Then, after 1898, the Spanish-American War stimulated a flow of power back to the presidency. In the 15th edition of Congressional Government, Wilson called attention to “the greatly increased power... given the President by the plunge into international politics.” When foreign policy becomes the nation’s dominant concern, Wilson said the executive “must of necessity be its guide: must utter every initial judgment, take every first step of action, supply the information upon which it is to act, suggest and in large measure control its conduct.” In another 15 years the First World War gave Wilson, now president himself, the opportunity to exercise those almost royal prerogatives. Then postwar disillusion again revived congressional assertiveness. In the 1930s Franklin Roosevelt, a mighty domestic president, could not stop Congress from enacting the rigid neutrality legislation that put American foreign policy in a straitjacket while Hitler ran amok in Europe.

Since Pearl Harbor, however, Americans have lived under a conviction of international crisis, sustained, chronic, and often intense. The imperial presidency, once a transient wartime phenomenon, has become to a degree institutionalized.

The most palpable index of executive aggrandizement is the transfer of the power to go to war from Congress, where the Constitution expressly lodged it, to the presidency. In the bitter month of June 1940, when the French prime minister pleaded for American aid against Hitler’s blitzkrieg. Franklin Roosevelt, after saying that the United States would continue supplies so long as France continued resistance, took care to add: “These statements carry with them no implication of military commitments. Only the Congress can make such commitments.” How old-fashioned this sentiment sounds today!

Presidents Truman, Johnson, Nixon, and Reagan thereafter assumed that the power to send troops into combat is an inherent right of the presidency and does not require congressional authorization, Nixon carried presidential prerogative even further when he took the powers flowing to the presidency from international crisis and turned them against his political opponents at home. In Nixon’s hands the claim to inherent presidential power swelled into the delusion that the presidency was above the law and the Constitution.

Congress, seized by a temporary passion to prevent future Vietnams and Watergates, enacted laws designed to reclaim lost powers, to dismantle the executive secrecy system, and to ensure future presidential accountability. The War Powers Resolution of 1973 was meant to restrain the presidential inclination to go to war. Congress set up select committees to monitor the Central Intelligence Agency. It gave the Freedom of Information Act new vitality. It imposed its own priorities—human rights and nuclear nonproliferation, for example—on the executive foreign policy.

For a season the presidency appeared in rout, Nixon’s successors—the hapless Gerald Ford and the hapless Jimmy Carter—proved incapable of mastering the discordant frustrations of the day. In 1973 the concern had been the excessive power claimed by a president as his inherent right. By the end of the 1970s the republic was consumed by an opposite concern—that the presidency had become too weak to do the job. In 1980 ex-President Ford said to general applause, “We have not an imperial presidency but an imperiled presidency.”

Half a dozen years later concern has shifted back from presidential weakness to presidential power. President Reagan demonstrated that the presidency was far from an insolvent office. The congressional reclamation of power after Watergate turned out to be largely make-believe. The War Powers Resolution had no effect in restraining presidents from sending troops into combat, whether in Lebanon or Grenada or Libya, Reagan reestablished the executive secrecy system. He brought the CIA back from its season of disgrace, made it once again the president’s private army, and sent it off, without congressional approval, to overthrow the government of Nicaragua.

In order to escape the CIA’s nominal obligation to report its dark deeds to congressional oversight committees and to evade the laws of the land, Reagan converted the National Security Council, heretofore a policy-coordination body, into an operating agency, and permitted it to indulge in the Iran-Nicaragua flimflam. Having placed the integrity and credibility of the United States in the hands of Iranian confidence men, the administration made exposure inevitable. And, when the inevitable exposure began, the administration took refuge in a bluster of incomplete, misleading, and, on occasion, false accounts of what its members had wrought.

The reaction against executive usurpation is already provoking a counter reaction, as it did after Watergate. We are beginning to hear again that the presidency itself is in danger. We are told that too zealous an inquiry into executive abuses will cripple the office. The prospect of a fifth consecutive failed presidency is leading some to conclude again that the fatal flaw lies not in the individuals occupying the office, but in the office itself. These apprehensions are unduly gloomy.

In the short run, if a president is inclined to do foolish things, surely a crippled presidency is better for the nation and the world than an unrepentant and unchastened one. And the crippling of a president who does foolish things does not mean a crippling of the presidential office. The reaction against Watergate did not prevent Reagan from having a successful first term, and it would not have handicapped Ford and Carter if they had been more competent.

Nor can one conclude from another failed presidency that there is something basically wrong with the system. The Constitution has never pretended to guarantee against presidential incompetence, folly, stupidity, or criminality. But through the separation of powers, it can guarantee that, when a president abuses power, corrective forces exist to redress the constitutional balance. As Senator Sam Ervin put it in Watergate days, “One of the great advantages of the three separate branches of government is that it’s difficult to corrupt all three at the same time.” The press, as a de facto fourth branch, serves as a powerful reinforcement of the corrective process.

No one need fear that the recurrent uproar against the imperial presidency will inflict permanent damage on the office. For the American presidency is indestructible. This is partly for functional reasons. The separation of powers among three supposedly equal and coordinate branches of government creates an inherent tendency toward inertia and stalemate. The executive branch must take the initiative if the system is to move. The men who framed the Constitution intended that it should do so. “Energy in the Executive,” as Alexander Hamilton put it in the Federalist Papers, “is a leading character in the definition of good government.”

Moreover, the growth of presidential initiative has resulted less from presidential rapacity for power than from the necessities of governing an ever more complex society. As the United States grew into a continental, industrial. and finally world power, the problems assailing the national polity increased vastly in number, size, and urgency. Most of these problems could not be tackled without vigorous executive leadership.

A third reason for the indestructibility of the presidency lies in the psychology of mass democracy. Americans have always had considerable ambivalence about the presidency. One year they denounce presidential despotism. The next they demand presidential leadership. Although they are proficient at cursing out presidents—a proficiency that helps keep the system in balance—they also have a profound longing to believe in and admire them. Reagan’s success in his first term expressed a widespread national desire for presidents to succeed, even when he proposed policies that made little sense and to which in many cases, if public opinion polls can be believed, a majority of Americans were opposed.

The presidency will survive. The real question is what leads American presidents into the imperial temptation. When the American presidency conceives itself as the appointed savior of a world in which mortal danger requires rapid and incessant deployment of men, weapons, and decisions behind a wall of secrecy, power rushes from Capitol Hill to the White House. The imperial temptation is the consequence of a global and messianic foreign policy. Twenty years ago an apprehensive Senate Judiciary Committee established a Subcommittee on Separation of Powers under the redoubtable chairmanship of Senator Ervin. In 1973 the Ervin subcommittee declared that “the movement of the United States into the forefront of balance-of-power realpolitik in international matters has been accomplished at the cost of the internal balance of- power painstakingly established by the Constitution.”

Whether this was a necessary cost the subcommittee did not say. But a prudent balance-of-power foreign policy confined to vital interests of the United States is surely not irreconcilable with the separation of powers. A messianic foreign policy, however, aiming at the salvation of the world and involving the United States in useless wars and grandiose dreams, is another matter. Vietnam and Iran/Nicaragua were the direct consequences of global messianism, Watergate an indirect consequence.

If America’s mission is to redeem a fallen world, then the United States must have a new constitution. And if a messianic foreign policy bursts the limits of our present Constitution, then the wisdom of the Framers is even greater than one could have imagined, for such a policy is hopeless on its merits and can only bring disaster to the American republic. The best insurance against a revival of the imperial presidency would be the revival of realism, sobriety, and responsibility in the conduct of foreign affairs.

Arthur Schlesinger Jr. was a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian. He served as Special Assistant to President Kennedy from 1961-1963.

For more TNR, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.